In ‘Troubadour,’ Lex Liang Reimagines Nashville’s Glittering Beginnings— One Rhinestone At a Time

In January 2016, Lex Liang and Alliance Theatre artistic director Susan Booth were deep in the throes of technical rehearsal for the violent drama “Disgraced,” when the costume designer turned to her and asked, “When do we get to do something fun and feel good?” That’s when Booth first dangled the idea of designing the midcentury costumes for Atlanta playwright Janece Shaffer and Sugarland singer-songwriter Kristian Bush’s fledgling musical “Troubadour” in front of Liang.

“It was an irresistible combination,” recalls Liang, speaking from his NYC-based LDC Design Associates. “It was Susan, it was Janece, it was the Alliance, it was country music and it was rhinestones. That pretty much checks all my boxes. Saying no never crossed my mind!”

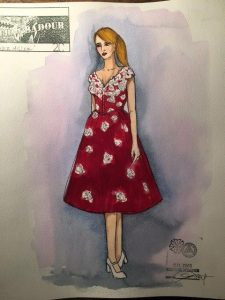

Inspired by the transformative Technicolor country and western costuming by real-life eastern European tailors Nudie Cohn and “Rodeo Ben” Lichtenstein, Shaffer had penned a love letter to these immigrant pin cushion pioneers while crafting a heart-warming romantic comedy. Bush then added a baker’s dozen catchy (not to mention eerily era accurate) songs to the effort and Shaffer’s story sprang to life.

“Troubadour,” running through Sunday at the Alliance, tells the story of the waning days of King of Country Bill Mason’s (Radney Foster) career and whether his son, Joe (Zach Seabaugh) has what it takes to transform the family business into art. Along the way, Joe meets Inez (Sylvie Davidson), a talented Tuscaloosa songwriter and Izzy (Andrew Benator), a quip-equipped genius tailor who is secretly squirreling away rhinestones by the bushel.

For Shaffer, the creative process began while roaming a display of iconic country and western costumes at Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame. The challenge for Liang was bringing the clothes from Shaffer’s painstakingly researched script to the stage, from Bill Mason’s simple 1930s and ‘40s God-fearing church clothes to Joe’s future-focused “Electric Cowboy”-inspired ensembles that usher in the 1950s.

“One of my favorite things about my job is each show is like attending a graduate school class, whether it’s a time period or a style,” says Liang. “With this show, it’s really the niche of a niche of a niche. We’re talking about 1940s Nashville going into the 1950s. But those iconic styles of the ‘50s hadn’t happened yet. We’re in the nascent stages of the decade. So we looked more toward the late 1940s for our overarching aesthetic.”

As Liang went through the photographic research of the period, inspiration  struck. As he shuffled through the black and white images of southern folk and church singers, mainstream use of an emerging technology greeted him at the dawn of the decade — Kodacolor film. “As you enter the 1950s, the images start to be in color,” he explains. “It was a beautiful transition in the research process that we were able to emulate on stage.”

struck. As he shuffled through the black and white images of southern folk and church singers, mainstream use of an emerging technology greeted him at the dawn of the decade — Kodacolor film. “As you enter the 1950s, the images start to be in color,” he explains. “It was a beautiful transition in the research process that we were able to emulate on stage.”

One notable explosion of color necessary for “Troubadour” was the scene-stealing green suit Izzy creates for Joe at the end of Act One.

“In rehearsals, Susan Booth would say things like, ‘You know, Lex, it would be great if that green suit got applause when Zach walks out in it,’” Liang recalls laughing. “I told her, ‘OK, gauntlet thrown, Susan. Challenge accepted!’ Testing my creativity and our costume shop’s creativity is always the goal. You’re always wanting to give people something they want to see and something they’re surprised to see. The green suit in particular was a challenge from the get-to, primarily because it’s a green suit. How do you make it not look garish but have it be respectful to the aesthetic of Nudie Cohn’s work? The clothes had to tell the story but not stop the show.”

On the opening night of “Troubadour,” Liang, fortified by a couple of glasses of wine, was in the audience, along with everyone else eagerly awaiting the emerald ensemble’s entrance. Says Liang: “The scene is brilliantly written so you’re sitting there as an audience member asking yourself, ‘How awful is this thing going to be?’ It’s a transitional moment for Joe, it’s a release from these repressive chains that have been holding him down, either because of societal expectations or because of his father. It’s also a moment for Izzy to show us his goods, what’s he’s capable of. If we did our job right, that moment in the show should elicit a joyful reaction.”

The first glimpse of Izzy (and Lex’s) sartorial spectacle occurs early in the musical’s first act when the tenacious tailor sneaks into Joe’s dressing room to present him with an eye-popping electric blue shirt. In rehearsals, when Liang first showed up with the shirt for Zach Seabaugh, the teenager’s initial reaction mirrored his character’s. “When Zach saw the clothes on the hanger, he took a step back and chuckled,” recalls Liang. “But when he tried on the shirt and looked at himself in the mirror, there was this ear-to-ear grin. By the end of the fitting, Zach said, ‘You know, I may need you to dress me for a red carpet at some point.’ When someone wants you to dress them in real life, you know you’ve hit the mark.”

Surveying his far more traditional outfits from the era, Radney Foster’s reaction surprised the costume designer. Says Liang: “Radney was impressed about the authenticity of the costumes, in spite of how boring his character’s clothes are. It was incredibly heartening. Sometimes even when an actor is playing a character who isn’t flashy, they still want to look good in their clothes. But Radney was incredibly supportive and appreciated how historically correct his character looked, even though it’s incredibly humble clothing.”

Joe and Inez’s outfits for “Troubadour’s” finale also presented a challenge for Liang and his staff — how do you visually represent the future of country music, the ushering in of Hank Williams, Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley as the clothing accompaniment to Kristian Bush’s Sun Records-steeped “American Original” big finish?

“We had to create this pendulum for Joe where it would swing one way and be too extreme for the character and then it swings back, in a way that is really acceptable,” says Liang. “The goal was to get that pendulum to hit stasis for us to embody it and for Joe and the audience to say, ‘This feels right.’”

And yes, Liang knows how many rhinestones he and the Alliance costume shop went through in order to bring “Troubadour” to sparkling life on stage, too: “We went through at least 20 gross and each gross is 144 so we’re talking a few thousand.” But as Dolly Parton will tell you, even rhinestones are an art. “You have to be judicious because they can be overpowering,” explains Liang. “You have to start small because you can’t undo them. You use a colored version and that kicks up what you’re trying to see. And then, there are the crystal ones, that just light up like fire. You use those sparingly. The rhinestone game is not ‘Let’s make a disco ball.’ You have to use them in a specific way to get the punch and to add to the design of the costume. It’s very strategic.”

For “Troubadour’s” finale, audiences who look closely at Joe’s ensemble will note an homage to Izzy’s transformative tailoring trajectory in the musical — a familiar blue shirt peeking out under Joe’s white and blue apparel.

Explains Lex Liang: I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to bookend the show and Joe’s personal journey if we brought back that first blue shirt?’ In the first act, he’s afraid of it, he says it’s too much for him to wear. But by the end of the show, he’s given in to his greater picture of himself. He’s given into his destiny.”

“Troubadour” production photos by Greg Mooney/courtesy of the Alliance Theatre.

Rehearsal photos by A’riel Tinter/courtesy of the Alliance Theatre

“Troubadour,” a world premiere musical by Janece Shaffer and Kristian Bush, directed by Susan V. Booth runs through Feb. 12 at the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta. For tickets: alliancetheatre.org.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.