A Conversation With Country Legend Bill Anderson At Decatur Book Festival!

Whisperin’ Bill Anderson is in the Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, Georgia Music Hall of Fame and the Georgia Broadcasters Hall of Fame but the 78-year-old country legend didn’t beam at his book launch Sunday afternoon until I described him as “a graduate of Avondale High and the pride of Decatur, Georgia.”

Whisperin’ Bill Anderson is in the Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, Georgia Music Hall of Fame and the Georgia Broadcasters Hall of Fame but the 78-year-old country legend didn’t beam at his book launch Sunday afternoon until I described him as “a graduate of Avondale High and the pride of Decatur, Georgia.”

The Grand Ole Opry fixture and the singer/songwriter behind “Still,” “City Lights,” “Po Folks,” “Tips of my Fingers” and “Mama Sang a Song” was back in his hometown over the weekend to help close out the 11th annual AJC Decatur Book Festival with a 45-minute conversation with fans and former neighbors at the Decatur Presbyterian Church.

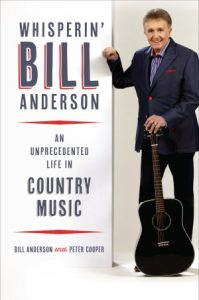

His new memoir, “Whisperin’ Bill Anderson: An Unprecedented Life in Country Music” was published last week by his alma mater, The University of Georgia Press, where he earned a journalism degree before the bright array of Nashville’s city lights beckoned.

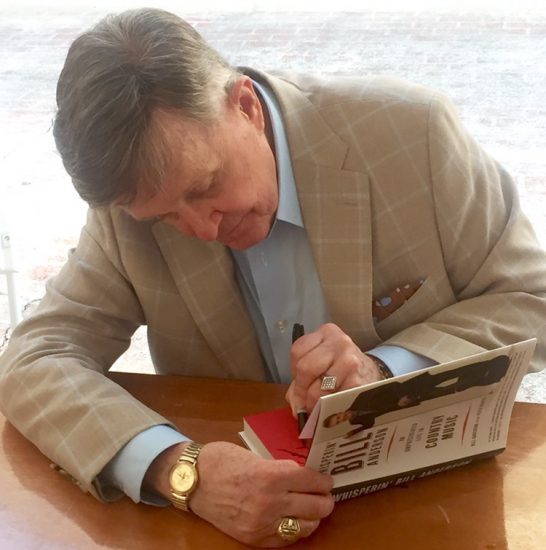

I had the great pleasure of interviewing Anderson about the book and his 60-year career in country music. Here’s an edited version of our conversation. Unfortunately for readers, I wasn’t able to replicate Anderson pulling out his old acoustic and performing “Still” on the spot with a congregation of fans singing back up on the chorus. You just had to be there.

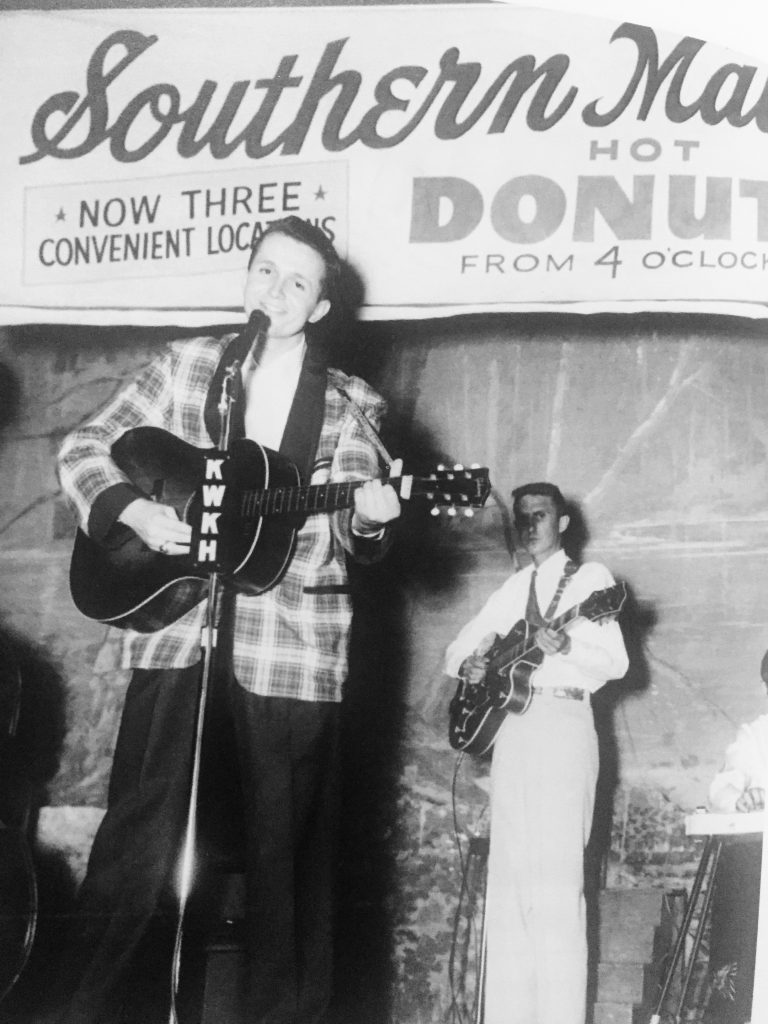

Eldredge: Take us back to the beginning. You were a 19-year-old DJ at WJJC in Commerce, Georgia. You lived on the third floor of the expansive three-story Hotel Andrew Jackson and on evening of August 27, 1957, it was stifling hot. So you grabbed your guitar and took to the roof. What happened next changed your life forever.

Anderson: It was a beautifully clear August night. I remember it like it was yesterday. I sat on this old piece of lawn furniture up there and looked at the stars and looked at the few lights there were in Commerce, Georgia. My father told me later he was convinced that I had the imagination to be a songwriter if I could look down at Commerce, Georgia and come up with “The bright array of city lights as far as I can see.” [audience laughs]. That song, “City Lights,” recorded by Ray Price, became my first hit.

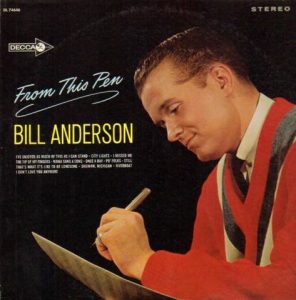

Eldredge: Published by your alma mater, The University of Georgia Press, your new memoir, “Whisperin’ Bill Anderson: An Unprecedented Life In Country Music” is an expanded and updated edition of your first 1989 autobiography. Why was now the right time for a book?

Anderson: I wrote the first book when I thought my career was over. I started out in the late 1950s and I thought that thirty years was a good run. I might as well write it all down for posterity. Turns out, my career wasn’t over at all. That’s what the new book is about. I started writing again and co-writing with the young country stars who were coming up and I ended up having a second career. Hopefully, my story will inspire people not to give up when they think maybe they should.

Eldredge: Your life changed forever again in the early 1990s with the simple act of walking into a hair salon on Music Row. A stylist friend handed you Vince Gill’s phone number and told you to call him and suggested you two should co-write together. But you were a little nervous about calling him. You write in your memoir, “The game has changed. Maybe your best days are behind you.” But you picked up the phone and called the number and something remarkable came out of the other end of the phone.

Anderson: I didn’t think Vince Gill had any idea who Bill Anderson was. And if  he did, he probably considered me some dinosaur from back in the day. The reason I put off calling him was because I was kind of intimidated. He was the hottest artist in country music at the time and he was writing his own songs. And then one day, I don’t know what made me do it, but I called the number. And I got Vince Gill’s voicemail and it said: “Hi, this is Whisperin’ Gill…” [audience laughs]. Not only did he know who I was, he was stealing my act! I left my number, he called me back and it was start of a wonderful, wonderful friendship and we ended up writing a couple of songs together, including “Which Bridge To Cross (Which Bridge To Burn)” and it went to number one. It jump-started the second half of my career. Before I knew it, I didn’t have to call the young songwriters in Nashville. They were calling me.

he did, he probably considered me some dinosaur from back in the day. The reason I put off calling him was because I was kind of intimidated. He was the hottest artist in country music at the time and he was writing his own songs. And then one day, I don’t know what made me do it, but I called the number. And I got Vince Gill’s voicemail and it said: “Hi, this is Whisperin’ Gill…” [audience laughs]. Not only did he know who I was, he was stealing my act! I left my number, he called me back and it was start of a wonderful, wonderful friendship and we ended up writing a couple of songs together, including “Which Bridge To Cross (Which Bridge To Burn)” and it went to number one. It jump-started the second half of my career. Before I knew it, I didn’t have to call the young songwriters in Nashville. They were calling me.

Eldredge: You recall in the book that when you hit Vince Gill with that phrase, “Which Bridge To Cross, Which Bridge To Burn” that day during a writing session in 1994, he got an odd expression on his face.

Anderson: I didn’t know a lot about Vince Gill’s personal life. I didn’t know that he had fallen deeply in love with a Christian singer named Amy Grant. Vince knew exactly what I was talking about with that.

Eldredge: We’re sitting in Decatur, Georgia for the launch of your new memoir, a town that you have a deep connection with. You grew up here. You went to school at Avondale High. For those of us who weren’t around when you were a teenager, can you discuss your very first band as a teenager, The Avondale Playboys, and is this true, you had a fiddle player named Meatball?

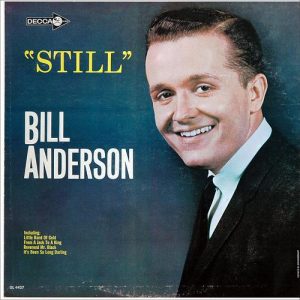

Eldredge: In 1958, you met a Nashville record producer who as far as I’m concerned ranks right up there with George Martin and Phil Spector. You describe him in your book as one of the architects of The Nashville Sound. But when Owen Bradley first met you as you recall in the book, he told you, “Well, son, you’re not the greatest singer I’ve ever heard but you sure do write some terrific songs.” He spent the next 20 years producing your records and overseeing some of your biggest hits, including “Still,” “Po Folks,” “City Lights” and “Mama Sang A Song.” How did Owen Bradley capture the purity in those records?

Anderson: That’s a great question. But keep in mind, Owen Bradley produced a few other singers who had just a little success too, folks like Patsy Cline, Conway Twitty, another gal who grew up here in DeKalb County, Brenda Lee and a gal you may have heard of, Loretta Lynn. I was in the presence of a master. What he brought to my career was that he could see things objectively that I could not. When we had a bit of success in the early ‘60s with a song called “Mama Sang A Song” where I talked a little bit and sang a little bit, he picked up on that becoming my trademark. But “Mama Sang A Song” was kind of a religious song. It had a lot of old church hymns in it. Owen told me, “What you need to do is take that formula and write me a love song about a man and a woman and bring it in here and I think we can take your career to the next level.” He was quite prophetic. That’s how I ended up writing “Still.” From that point on, Bill Anderson had a style. And that was all because of Owen Bradley.

Eldredge: There’s an amazing story behind what inspired “Still.” Your career was on the rise in Nashville with hits like “City Lights” and “Po Folks” and you were back here in Atlanta visiting your parents when the local TV station called to invite you in for a live interview. Problem was, your ex-girlfriend worked there. The ex-girlfriend who had run off with the station’s weatherman, right?

Eldredge: There’s an amazing story behind what inspired “Still.” Your career was on the rise in Nashville with hits like “City Lights” and “Po Folks” and you were back here in Atlanta visiting your parents when the local TV station called to invite you in for a live interview. Problem was, your ex-girlfriend worked there. The ex-girlfriend who had run off with the station’s weatherman, right?

Anderson: You had to bring that up, didn’t you?! [audience laughs].

Eldredge: You got a pretty terrific song out of it.

Anderson: Yeah, I did. It’s out there now so I’ll tell it. The station was WSB. She was working at the station and she had married the station’s weatherman. He was a lot bigger star at the time than I was. When I went down there to the station, I drove into the parking lot and she was standing right there at the glass door and I thought, “Whoa, boy.” As fate would it, I had my radio tuned to the country station here in Atlanta, WPLO and just as I drove into the parking lot, the disc jockey played “She’s Just A Girl I Used To Know” by George Jones. [audience laughs]. Whew. That hit me hard. I managed to get my car parked. I parked my Cadillac next to her Chevrolet. [audience laughs and applauds]. I shouldn’t have said that! I went into the station and everything turned out all right. I had moved on. I wasn’t still in love with this girl. But when I got home to Nashville a couple of days later, there was this lingering feeling I had. I couldn’t get it off of my mind. I got up out of bed at 3 o’clock in the morning and wrote “Still.”

Eldredge: You’ve made a confession, so I’ll make one now. Your version of “Still” wasn’t the first one I was exposed to. The one I heard was recorded by your fellow Georgia Music Hall of Fame inductee James Brown for his 1979 album “The Original Disco Man.” What did you think of James Brown’s version of your song?

Anderson: I thought, “Lord, anything can happen, can’t it?” [audience laughs]. Not only did James Brown record “Still,” Aretha Franklin recorded one of my songs. Dean Martin recorded more than one of my songs. Strange things happen when you grab a guitar and write down two or three chords. You never know where your songs will end up. My version of “Still” was three minutes and I whispered most of it and James Brown’s version was seven minutes and 58 seconds and his sounded like [imitating Brown’s trademark screech] “STIIIIIIILL!” It was pure entertainment. I loved it. I wouldn’t part with my copy of that for anything.

[amazon_link asins=’0820349666,1458405095,B00BFR3GBM,B000000CZO,B003LXZFVW,B005ILYN04,B000EMGISW’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’eldredgeatl-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’a451c87e-0eea-11e9-8ef2-35d9337fa2eb’]

Eldredge: You are immortalized in a chapter of Atlanta author Paul Hemphill’s  1970 book, “The Nashville Sound.” You gave a wonderful blurb for the book, “The first real book about our music. The people, the songs, the places, all come to life in these pages.” Some of Paul’s family members are here today. You gave Hemphill complete access — he was in the recording studio with you, he slept at your house and rode the tour bus. Why did you give him such access to your life?

1970 book, “The Nashville Sound.” You gave a wonderful blurb for the book, “The first real book about our music. The people, the songs, the places, all come to life in these pages.” Some of Paul’s family members are here today. You gave Hemphill complete access — he was in the recording studio with you, he slept at your house and rode the tour bus. Why did you give him such access to your life?

Anderson: I trusted him. I believed in the book and I had been reading his columns for years in the Atlanta newspapers. He was an Auburn graduate but I didn’t hold that against him. I liked Paul personally and I knew what his goal was. He wanted to write an inside book about country music. He wasn’t there to make fun of us like a lot of other writers who were coming into Nashville to write about us at the time. They put us down after coming down and accepting our hospitality, they would write terrible things about us. I knew Paul wasn’t aiming to do that. He went out on the road with us. He ended up staying at my house while I was on tour. He wrote a lot of “The Nashville Sound” sitting at my dining room table. Before it was over, he became one of us.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.