‘Oh, Honey, I Ain’t No Icon’: Remembering Country Queen Loretta Lynn, 1932-2022

In an era filled with young micromanaged, media trained country acts, interviewing Loretta Lynn was something akin to trying to lasso a twister. Often, you had absolutely no idea where the conversation was headed next but the ride was always completely incomparable. The pride of Butcher Hollow, Kentucky had zero filter. Perhaps, not surprisingly, the only other superstar I’ve ever interviewed who is just is candid is Lynn’s country contemporary and fellow Southerner Dolly Parton.

As the world mourned the loss of the country queen who died in her sleep early Tuesday at age 90, I listened back to our interviews together over the years. One thing stuck out — Loretta Lynn could make you laugh like nobody’s business. I’m talking, rib-hurting, tear-inducing laughter, too.

For instance, in a 2002 interview, Lo-retta kicked things off by casually mentioning the upcoming yard sale she was planning at her Hurricane Mills, Tenn. ranch. When I asked the obvious follow up question, her response was 100-proof Loretta: “What am I selling? Really just a bunch of junk. My house looks like a trash can. It’ll all be real cheap. I’ve also just closed down an office here, so I have a lot of desks. I’ll put one aside for you if you want!”

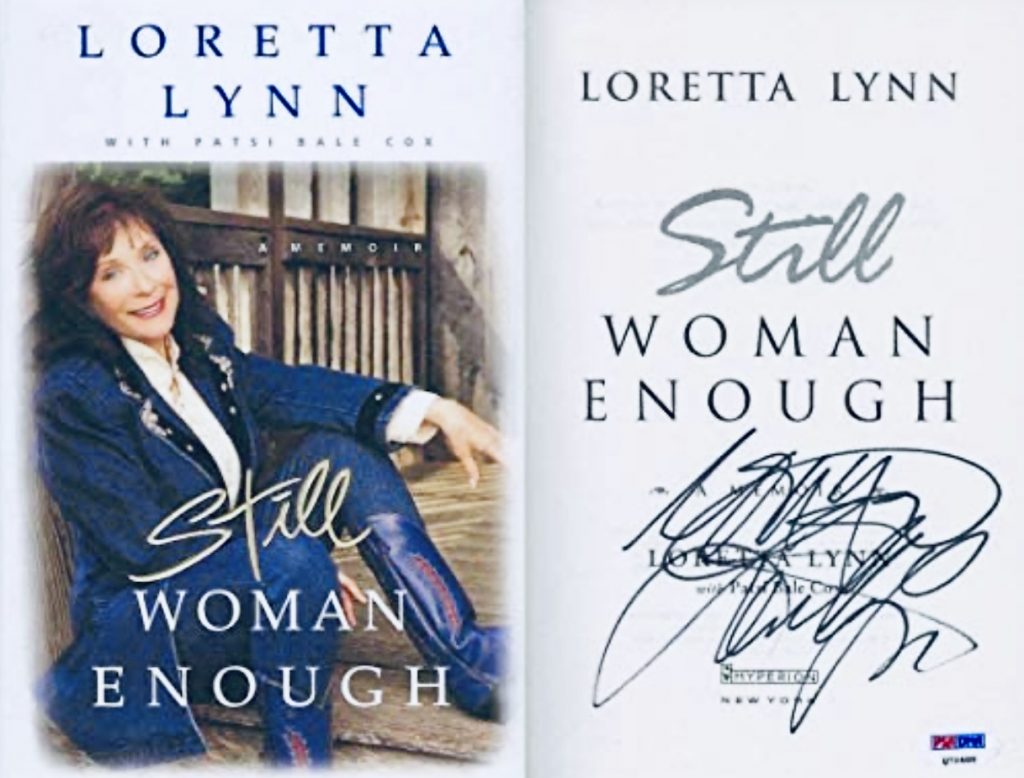

When you interview famous folks for a living, there’s this unspoken agreement between the celebrity and the reporter — the focus should always be squarely on them, their new project, new album, book or movie. That’s why the first time we chatted, I was caught completely off guard when Lynn suddenly asked, “So, how are you doin’?” When I sheepishly explained that my wellbeing wasn’t the focus of our conversation, Lynn laughed and conceded, “Sorry, darlin’. You know, that’s just how I am.”

The occasion for our conversation was the release of her second memoir “Still Woman Enough,” the follow up to her acclaimed 1976 autobiography “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” A book that, in turn, inspired the 1980 bio pic starring Sissy Spacek — a role for which she won an Oscar. In the second book, Lynn was free to share some of the more personal and painful stories about her hard drinking, two-timing husband Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn, who had died in 1996.

I asked her why the stories weren’t included in “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” She replied flatly, “Because he wouldn’t have let me. He’s gone now and maybe by writing about those times, I can help out some women in the same spot a little bit. [Daughter] Cissie got real upset when she saw that stuff. I told her, ‘Your daddy always told me to tell the truth and that’s what I’m doing. Now, cool it or I’ll put the rest of the stories in!’”

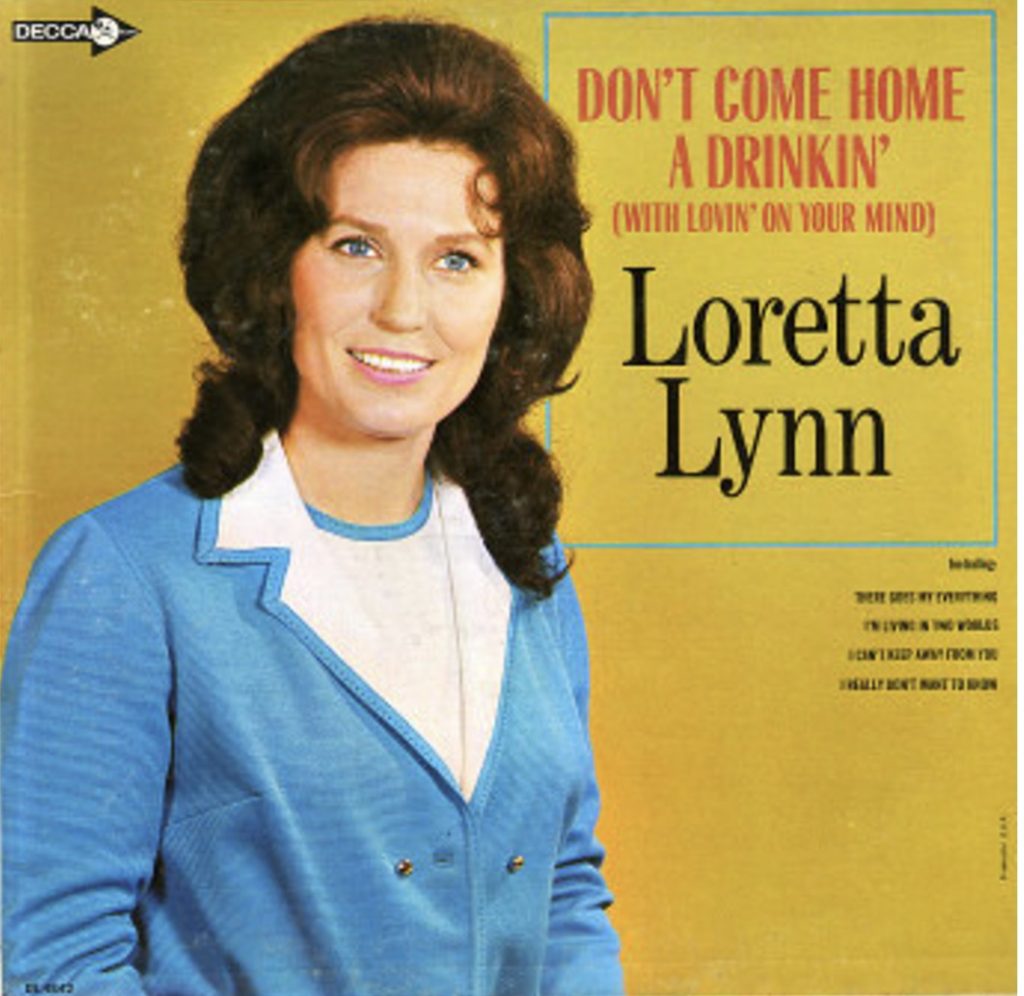

Like many of her millions of fans, aside from her iconic singing voice, what always pulled me into her material was Lynn’s incomparable writing voice. She connected best when singing her self-penned, pro-woman, don’t-take-any-manure country classics such as “Don’t Come Home a-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)” and “Your Squaw Is on the Warpath,” all recorded at Bradley’s Barn by her equally iconic producer Owen Bradley, who recorded all of Lynn’s and pal Patsy Cline’s biggest hits. In 1975, Lynn even found herself banned from country radio when she released “The Pill,” a sly song she co-wrote about women taking control of their reproductive cycles. Having birthed four of her six children by age 20, Lynn knew much about the song’s subject matter. The controversy helped Lynn land “The Pill” straight onto Billboard’s Hot 100 pop chart.

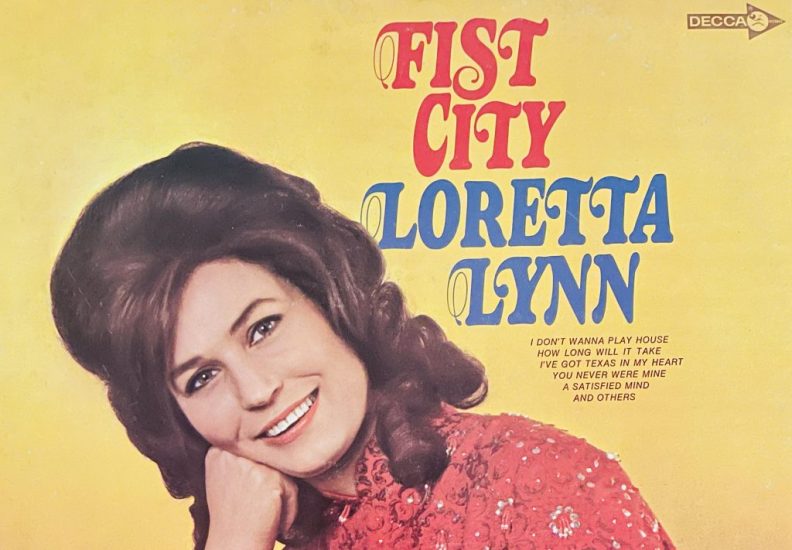

For my money, Lynn’s “Fist City” is among the finest two minutes and 10 seconds ever committed to tape in Nashville. Decades before Carrie Underwood took a Louisville slugger to her boyfriend’s four-wheeler, Lynn was hitting the charts with “Fist City.” Sample lyrics: “Ya better detour around my town/Cause I’ll grab you by the hair of the head/And lift you off the ground/I’m here to tell you, gal, to lay off a my man/If you don’t want to go to Fist City.”

In 2008, I finally mustered up the courage to ask her to confirm that the philandering husband and the “other woman” at the center of the 1968 hit was based on a true story.

“You betcha,” she replied, matter of factly without blinking. “I had come off the road and Cissie came home off the school bus crying one day. She told me that the old girl who drove the school bus was telling her she was gonna marry her daddy. I told Cissie, ‘Well, he’s gonna have to divorce me first.” That woman had my horse in her pasture. We had ourselves a little talk. I actually wrote that song sitting in a white Cadillac. Songs about cheatin’ have always done me right. Now Doo, he didn’t like some of those songs, but Doo ended up making us a lot of money over the years! I love to write. I’d rather write than sing. You can kinda tell things on yourself, but nobody knows what line is true and which one you made up!”

There was an economy to Lynn’s best work as well. In 2021, combing through old vinyl in a second-hand shop in Knoxville, I unearthed a copy of Lynn’s 1967 album “Singin’ With Feelin’.” The lead off track, “Bargain Basement Dress,” a Lynn original, brilliantly illustrates her songwriting acumen. It’s only 1:45, but in less than two minutes, she delivers a 12-round verbal beatdown with a series of increasingly lethal body blows: “Well, on a Friday night, you draw your pay/ And you take in the town/You leave me at home just to lose my mind/For you’re out messin’ around/Well, it’s four in the morning and you’re staggerin’ in/And you sure look a mess/With a smile on your face and out-stretched arms/And a bargain basement dress/I wouldn’t wear that dress to a dogfight/If the fight was free/And the bargain basement dress ain’t enough/To get your arms around me/Well, you say when a man works hard all week/He deserves to play or rest/But honey, that ain’t right, so get out of my sight/With that bargain basement dress/Now, I took all I’m a-gonna take/And I’m leavin’ you the rest/Tell you what I’ll do, I’ll just leave you/That bargain basement dress.”

Sometimes, because she was speaking with an Atlanta reporter, a geographically specific memory would surface. That’s how I first heard about an impromptu slumber party Lynn had with pal Tammy Wynette, following a 1980s gig in Macon. “You see, Tammy was in an Atlanta hospital getting surgery for some of that scar tissue she had,” she recalled to me. “My sister Peggy Sue and I heard a knock on our hotel room door around 1:30 in the morning. I looked through the peephole and said, ‘That sure as heck looks like Tammy Wynette out there in a housecoat.’ She had escaped and had gotten a pilot to fly her down to Macon. I said, ‘Tammy, you’re gonna get caught.’ She said, ‘Shoot, I’ll be back in that bed by daylight. They’ll never know.’ We sat up all night gossiping about George Jones.”

Without blinking, Loretta then launched into a tale about the time she and Patsy Cline decided they were done having children and decided Cline’s husband Charlie Dick and Doo were going to have vasectomies. “We got them appointments at the same time to be fixed,” Lynn recalled laughing. “Charlie went in and got it done, and ol’ Doo, well, he headed for the hills. Two weeks later, I got pregnant with the twins, Peggy and Patsy.” I then asked if she ever told The Lynns that particular story. Loretta’s reply while laughing uncontrollably: “Only about 200 times!”

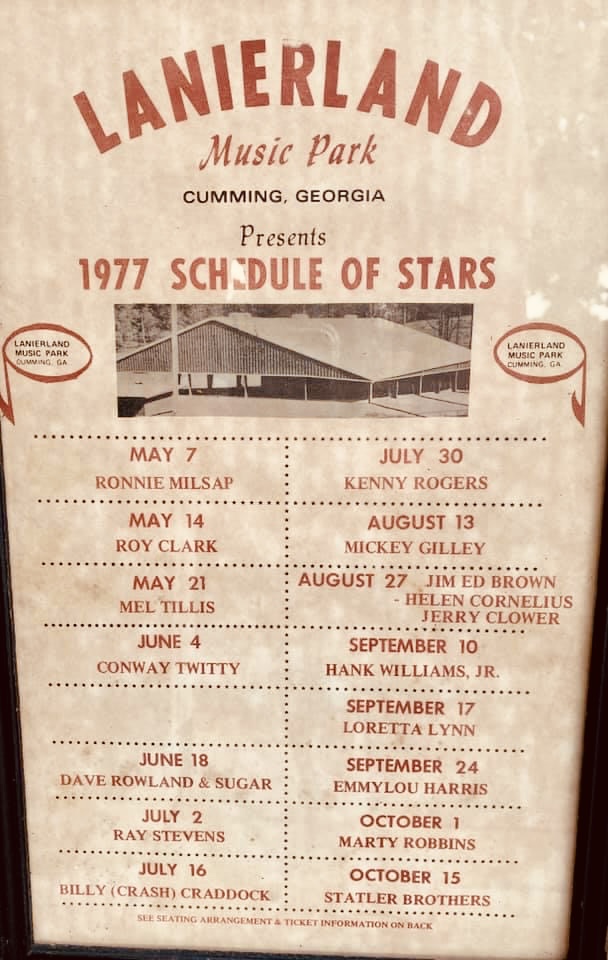

Seeing Loretta Lynn perform live, particularly at the now-late, lamented Lanierland, the bare bones, sawdust on the floor, folding metal chair outdoors country venue in Cumming, Georgia, was a treat. For starters, members of the press who made the drive out from the city to cover a show were routinely invited backstage where Mama Lois Heard would put out a Southern spread for all of the performers and road crew. We’re talking literal piles of home-cooked fried chicken, meatloaf, black eyed peas, sweet potato casseroles, green beans and cornbread for all. And there, standing a few feet away, Loretta herself would be fixing herself a plate — sometimes to her onstage detriment.

Later, at that particular 2003 Lanierland appearance, wearing a gorgeous white gown with pink and gold flowers, Lynn lamented to the crowd, “I almost didn’t get this dang thing on tonight. They always feed us real good here. The sweet taters are the best. I won’t feel bad when this dress busts in a minute!”

Later in the set, when someone in the audience shouted a request for “Coat of Many Colors,” a song written by and made famous by her friend Dolly Parton, Lynn rested a hand atop her eyes and scanned the audience. “I’m not Dolly, can’t ‘cha tell?,” cracked Lynn. “What part of me you lookin’ at, honey? Must be my belly!”

The last time I saw Lynn perform live was at the Cobb Energy Centre in the summer of 2008. At age 73, she was seated onstage and apologized when she would occasionally forget a verse or two of one of the songs from her iconic songbook as the audience sang along. Wearing a shimmering pink gown, Lynn admitted, “I don’t know if I did all of that song or not! It’s my age.” Immediately a voice in the back of the venue shouted, “It don’t matter, Loretta. We love you!” Clearly moved, Lynn replied, “I love you too, darlin’!”

For years, Lynn privately battled multiple health issues, including a 2017 stroke. In one of our conversations, I asked her about those supermarket tabloids that always touted dire headlines like “Loretta Lynn’s Brave Final Days.” “Oh, darlin’ I’m fine,” Lynn reassured me. “Usually, there’s a speck of truth in there, surrounded by a bunch of lies. But I sure do like to read ’em. Sometimes, my assistant will come back from the grocery store with three or four of ’em. He’ll say, ‘Well, lookee here, I didn’t know you did that.’ I tell him, ‘I didn’t know it either. Pass that on over here so I can see what I’ve been up to!'”

At the end of what would be our final interview, I used the word “icon” to describe her. It was the only time that Loretta Lynn politely pushed back on one of my questions.

“Oh, honey! I ain’t no icon,” she told me. “I don’t even know what one is. You’re dealing with a girl with a sixth-grade education. You got my manager sitting here a-grinning, though. You should talk to my kids. They’ll tell you I’m not no icon. Here I thought I was a country singer.”

Five Essential Loretta Lynn LPs

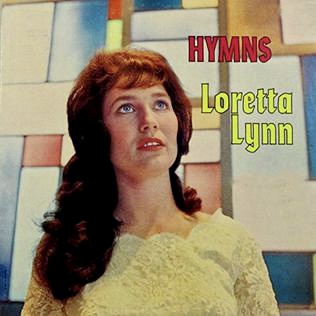

“Hymns,” 1965: Like Elvis, Tammy, Bill Anderson and practically every other country act, Lynn recorded a collection of gospel tunes, including a sublime version of “How Great Thou Art,” along with her opening original tune “Everybody Wants to Go to Heaven (But Nobody Wants to Die).”

“Country Christmas,” 1966: Recorded in July at Bradley’s Barn and produced by Owen Bradley with backing vocals by The Jordanaires, this seasonal classic features Lynn performing stripped down renditions of “Away in the Manger” and “White Christmas,” along with her inimitable originals “To Heck With Ole Santa Claus,” the title track and “I Won’t Decorate Your Christmas Tree.”

“Loretta Lynn Writes ‘Em and Sings ‘Em,” 1970: Ten years into her recording career, Lynn’s label Decca finally compiled an entire album’s worth of her original songs that were usually doled out a few at a time on her albums, along with a new song written for the collection, “I Know How.”

“Van Lear Rose,” 2004: This Grammy-winning comeback record produced by White Stripes rocker Jack White and featuring a line-up of songs all written by Lynn, “Van Lear Rose” sounds as if White and Lynn beamed themselves back to 1950s Memphis and holed themselves up in Sun Records with a couple of distortion pedals. A late-period burst of genius.

“Still Woman Enough,” 2021: On her last studio recording, produced by Johnny Cash’s son John Carter Cash and Lynn’s daughter Patsy Lynn Russell, “Still Woman Enough” is a final victory lap re-examination of some Lynn’s finest songs, including the title track, Honky Tonk Girl,” “One’s on the Way” and “You Ain’t Woman Enough” with friends Reba McEntire, Carrie Underwood, Margo Price and Tanya Turner stopping by to trade verses with the legend.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.