20 Years in the Making, Jazz Fans Celebrate the Release of ‘Becoming Ella Fitzgerald,’ a New Biography

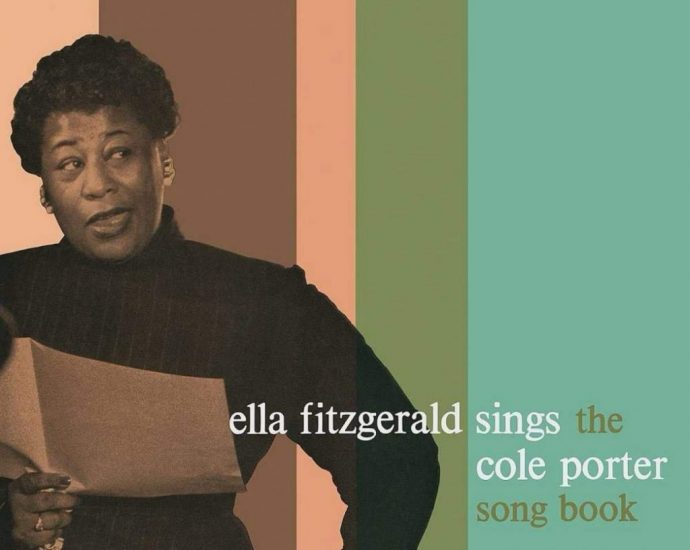

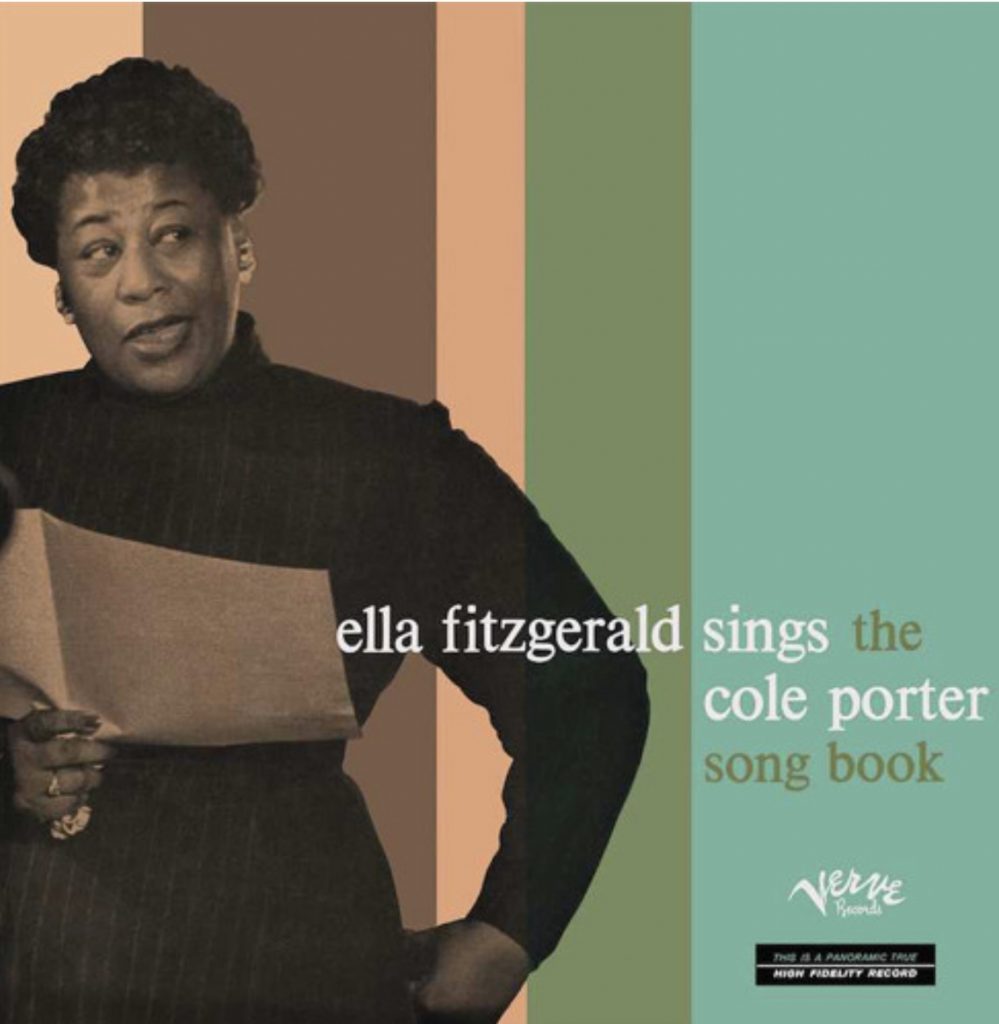

You could say author Judith Tick has been preparing to write Ella Fitzgerald’s biography her entire life. She grew up in a house where the iconic jazz singer’s LPs were front and center below the hi-fi (Tick’s mother, born in 1918, a year after Fitzgerald’s birth, would go to see Fitzgerald and her old band leader Chick Webb as a girl growing up in Boston). As a teenager, Tick memorized the witty, double-entendre tinged songs on the two-record set “Ella Sings The Cole Porter Songbook” and took a sheet music book of Porter compositions to Smith College with her where she studied feminism and music. Tick would go on to teach both of those subjects at Northeastern University, where she is now professor emerita of music history.

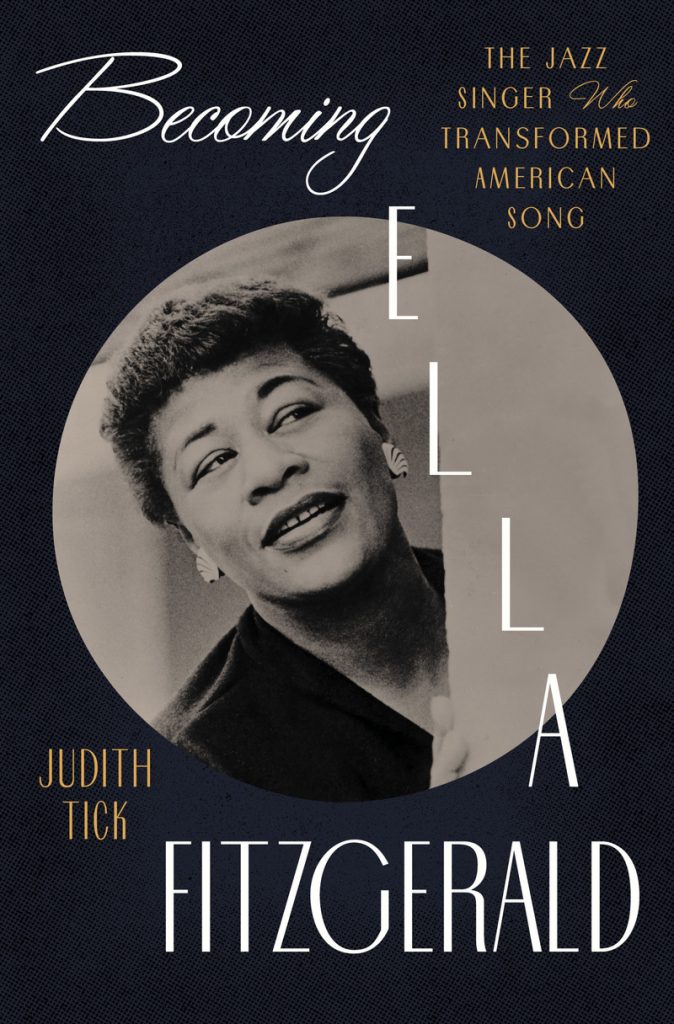

For the past two decades, Tick has been interviewing for, researching and writing “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song” (W.W. Norton & Company, $40). Released in December, the long-anticipated 560-page book is finally being devoured by fans. As the first woman music scholar to tackle Fitzgerald in a definitive biography, Tick brings a much-needed feminist lens to Fitzgerald’s 50-year career even as the ever-retiring artist herself wasn’t especially keen to publicly tout her trailblazing accomplishments with the press.

Thanks to new digital archives, Tick was able to dig into pivotal coverage of Fitzgerald’s early career reported by the nation’s Black newspapers, including the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Defender and the Atlanta Daily World. In addition to unearthing previously unread interviews with the singer and talking to Ella insiders, including musician Buddy Bregman (who had the arduous task of arranging 32 Cole Porter tunes for 1956’s “Ella Sings the Cole Porter Songbook,” the inaugural offering in what would become the signature songwriter tribute series of Fitzgerald’s career). Tick also paints a three-dimensional portrait of Fitzgerald’s longtime manager and Verve Records founder Norman Granz, whose love of the singer transformed her career, making her an indelible artist in the history of 20th century pop music. While Fitzgerald died in 1996 at age 79, her new musical output continues unabated at Verve as archivists at the label keep discovering previously unreleased concerts Granz recorded for the label in the 1950s and early 60s in the Verve vaults.

The following Eldredge ATL conversation with “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald” biographer Judith Tick has been edited for clarity and length.

Eldredge ATL: One thing that sets this book apart is the subject was no longer with us when you began your research. There had been some sizable road blocks put up for earlier Ella Fitzgerald biographers during her lifetime, right?

Tick: I think her office and Norman Granz in particular helped the side of Ella who wanted privacy. The privacy element also was exaggerated by her own illnesses, starting with her heart problems in the late 1980s. For me, I’d also say another big motivation for this book was feminism and revisionist scholarship. I’m a second-wave feminist historian and I’m used to seeing women neglected and misinterpreted in the mainstream, partly out of willful ignorance, partly out of historical interest. So, when I read that Norman Granz said that Ella had no idea of who she was, it just made me more determined to prove him wrong. In fact, she had a strong sense of her artistic identity. She didn’t want people to focus on her private life. She didn’t believe that was important. So, I followed her.

The other distinguishing aspect of your Ella biography was by the time you were researching for “Becoming Ella,” so many of the nation’s iconic Black newspapers had been digitized and the decades of content was made available for online users, particularly for white audiences who didn’t have access to the original print issues distributed in Black communities.

Tick: In doing research, I immersed myself in Black newspapers. And as a white woman, a white person, I felt the gulf between my lived experience and Ella’s very strongly. I decided to immerse myself in the world she grew up in. Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Defender, the Baltimore Afro American, the New York Amsterdam News, the Norfolk Afro American. I learned how important music and entertainment was to the vitality of the new economy for Black people. I also got a different view of American racism by reading those sources.

It was fascinating to learn just how many obstacles were placed in Ella’s performance path due to racism in the American South. A 1938 dispatch from the Atlanta Daily World in particular paints a vivid picture of a segregated south where the right side of the city auditorium was reserved for Black fans while whites sat on the left. And yet, thanks to that concert account, you can sense the excitement of that midnight performance.

Tick: Absolutely. It transcended those boundaries, it transcended those ropes put down the middle of auditoriums and ballrooms. Another big push for me was the treatment of Ella as a female performer which I call ‘Jane Crow,’ a term well known in Black literature. Ella broke barriers of what Black women could do. When she was starting out, Black women were supposed to sing the blues mainly. Billie Holiday showed them you didn’t have to and so did Ella. That was a big turning point. When bebop came along and her great friend Dizzy Gillespie was popularizing it, she just went for it in a time when few women were daring to scat, bebop style. Betty Carter credits Ella with opening that door.

While Ella wasn’t leading protest marches, she was an activist in her own way. You quote Coretta Scott King from her remarks given in 1988 where she refers to Ella as “one of the heroines of our history.” Ella used music and the stage to create as you call it “social harmony.”

Tick: Yes, and so did Duke Ellington, so did Louis Armstrong and Count Basie. That was part of their mission. Maybe not explicitly stated in Ella’s case but she talked about it in interviews and in the tribute she wrote for Martin Luther King, Jr. [“He Had a Dream”]. She really believed in the power of music to unite us. She was also able to extract the essence of King’s message which was nonviolent protest.

You also cover Ella’s 1955 arrest in Houston where the police alleged she was arrested for gambling. But in reality, she wasn’t shooting dice in her dressing room. She got arrested for performing in front of an integrated audience. Reading your book, I learned Houston officials later received a lot of blowback after the arrest was made public.

Tick: They did. I have a friend, a musicologist who remembers how embarrassed some of the elite in Houston felt at this shameful set up. Norman Granz was a great civil rights activist. He insisted on those venues being integrated. Sometimes, it was terrifying. You never knew what was going to happen. One night in North Carolina a mob gathered, waiting for them because they were enraged at the integration that had occurred against their will and knowledge. They escaped with their lives. And Ella stayed on stage until everyone else left.

You also separate fact from fiction with Ella’s historic first booking at the Mocambo on the Sunset Strip in 1955. The famous story of course is that Marilyn Monroe, a dear friend of Ella’s, helped her secure the booking by promising to sit in the front row each night. In reality, she wasn’t there. But even Ella herself continued the myth by repeating that story in a 1972 interview.

Tick: Marilyn Monroe did help her get the booking. But the issue was not around Ella being a Black performer. The Mocambo was booking Black performers, it was jazz. Ella was too identified with a kind of music that the Mocambo club owner believed would not attract audiences. This was before she began recording the song book series so he didn’t know or understand the jazz/pop synthesis she was about to forge. He didn’t understand her universal appeal. He underrated the appeal of jazz as well.

“Jazz critics undervalued Ella. They put too much emphasis on whether or not she could deliver sensual readings of texts. They came up short in dealing with women, with Ella and with women in jazz.”

“Becoming Ella” biographer Judith Tick

Since you brought it up, I can’t speak to Ella Fitzgerald’s biographer without having you discuss her iconic song book series recorded for Verve Records in the 1950s and 60s. You had deli sandwiches with Buddy Bregman in his Los Angeles apartment, the guy who arranged 1956’s “Ella Sings the Cole Porter Song Book,” the inaugural songbook in the series. The quote that stunned me was when he told you, “I was never an Ella Fitzgerald fan, ever. I was more Broadway than jazz.” [Bregman’s uncle was legendary “Funny Girl” and Gypsy” Broadway songwriter Jule Styne and his daughter is Emmy-winning Tracey E. Bregman, a “Young and the Restless” daytime icon]. But for Norman Granz, that made him the ideal guy for this first songbook. Would it be an underestimation to say Buddy Bregman was a character?

Tick: (laughs) No, it wouldn’t. That’s why I loved talking to him. I just clicked with him right away. I saw all of those photographs from his entire career covering every single wall of his small apartment and I just understood him in some way. Maybe because he was of my father’s generation. He was a child of Broadway. He revered those songwriters in a different way than jazz musicians approached them. For jazz musicians in general, those songs were fodder for their own improvisation. For pop singers, they were fodder for their personalities. For arrangers like Nelson Riddle, he went with the pop singer personality like Frank Sinatra. But Buddy Bregman heard Ella when she said, “I want to be true to this material.” He didn’t push her to jam or to scat. He just embraced her aesthetic. And so, they sound very truthful.

There are so many moments while reading this book where my jaw just went slack.

Tick: Good! (laughs).

That moment at Zardi’s when they’re rehearsing the songs for the Porter song book and Bregman explains to you just how intentional Ella was about wanting to present herself as a blank canvas in service to the songwriter. Who else would do that? Who else would separate out their ego like that? You would never had seen Sinatra do that.

Tick: Right. Or Billie Holiday. But Ella brought jazz into the process in her own way, which was swing. Everything she touched in that Broadway repertoire had that vital element of swing. She was bringing jazz into it in the most authentic way. As the song book series grows, she became more invested in making them personal. By the time she does the Irving Berlin song book, she’s doing parodies of Ethel Merman. By the time [“Ella Sings The George and Ira Gershwin Song Book”] arrives with Nelson Riddle, they’re doing sophisticated arrangements. They’re very different from the earlier Buddy Bregman approach.

As a fellow feminist, I’d love to ask you to discuss the cover of the Ella Sings Cole Porter Song Book.” You describe the album cover photograph, writing “The photo dignifies her status as a modern, professional working musician. A Black woman without a white woman hairdo, posing assertively with her hand on her hip, holding a lead sheet in rehearsal.” I say this as an Ella fan, there were a lot of album covers over the years featuring Ella in some terrible wigs. Here is Ella with her natural hair in 1956 on the cover of a gatefold two-LP set that was selling for $9.95 in 1956 dollars. Why was that important?

Tick: Here she is going natural, not bothering to adhere to white norms. Here is a photograph of an assertive artist listening intently and running the show. It’s a strong statement from Norman Granz, who probably helped that cover come into being. It’s a different image of Black women. Now, Black women are coming into their own in the 1950s. They’re going to college. Ebony, Hue and Jet magazines are featuring articles about strong women, who are entrepreneurs, who are getting educated. And it’s definitely a trend that would have appealed to Ella’s base in the African American world of the 1950s. Ella was always adored by the public but with jazz critics, with the exception of [Metronome magazine and Los Angeles Times jazz critic] Leonard Feather and some others, I’d say Ella was undervalued. The critics put too much emphasis on whether or not she could deliver sensual readings of texts. They missed the sensuality and the originality in her voice itself. After all, Ella is touring the world and bringing the song books to audiences who don’t speak English. And they get it. They get “every time we say goodbye I die a little,” they get “Too Darn Hot.” They get the spirit through music as much as words. Jazz critics are now looking back on their own history and realizing that they came up short in dealing with women, with Ella and with women in jazz in particular and the history of vocal jazz in general.

You took such a nuanced approach to Norman Granz in this book. He is equal parts hero and villain.

Tick: Aren’t we all.

Without him, there wouldn’t be the records on Verve, the songbook series and the global elevation of Ella’s stage career. But Ella also sometimes viewed him, rightfully so, as an interfering presence.

Tick: Over time, our deepest friendships and our deepest relationships change. And that’s the case here. She loved Norman Granz and understood that he loved her. And he understood the gold they made together in the 1950s and 60s but then, he had his own life to live. He went to live in Europe. He couldn’t deal with America anymore. I want to pay tribute to [“Norman Granz: The Man Who Used Jazz for Justice”] biographer Ted Hershorn, without whom I could not have developed any understanding of who Norman Granz was. Ted takes a nuanced approach as well. It’s true that Granz struggled with the way Ella’s relatives behaved. Family matters are complicated. It’s so important to not think we know better than the people who are in the family. But in the end, when she wanted to make an album, he was there. He got the people, he found the material. He never stopped being a great manager for a great artist.

I had no idea until I read “Becoming Ella” that after Granz sells Verve and moves to Europe, the company doesn’t renew her record contract in 1966.

Tick: It’s all about business and profit. You’re as good as your last hit. And Ella just wasn’t making hits. But look at the competition in the mid-1960s. Aretha Franklin is coming up, you have the whole movement of soul, which had a big impact on Ella’s taste. There’s the folk movement. Who would be relevant from the 1950s if you had to compete with that milieu?

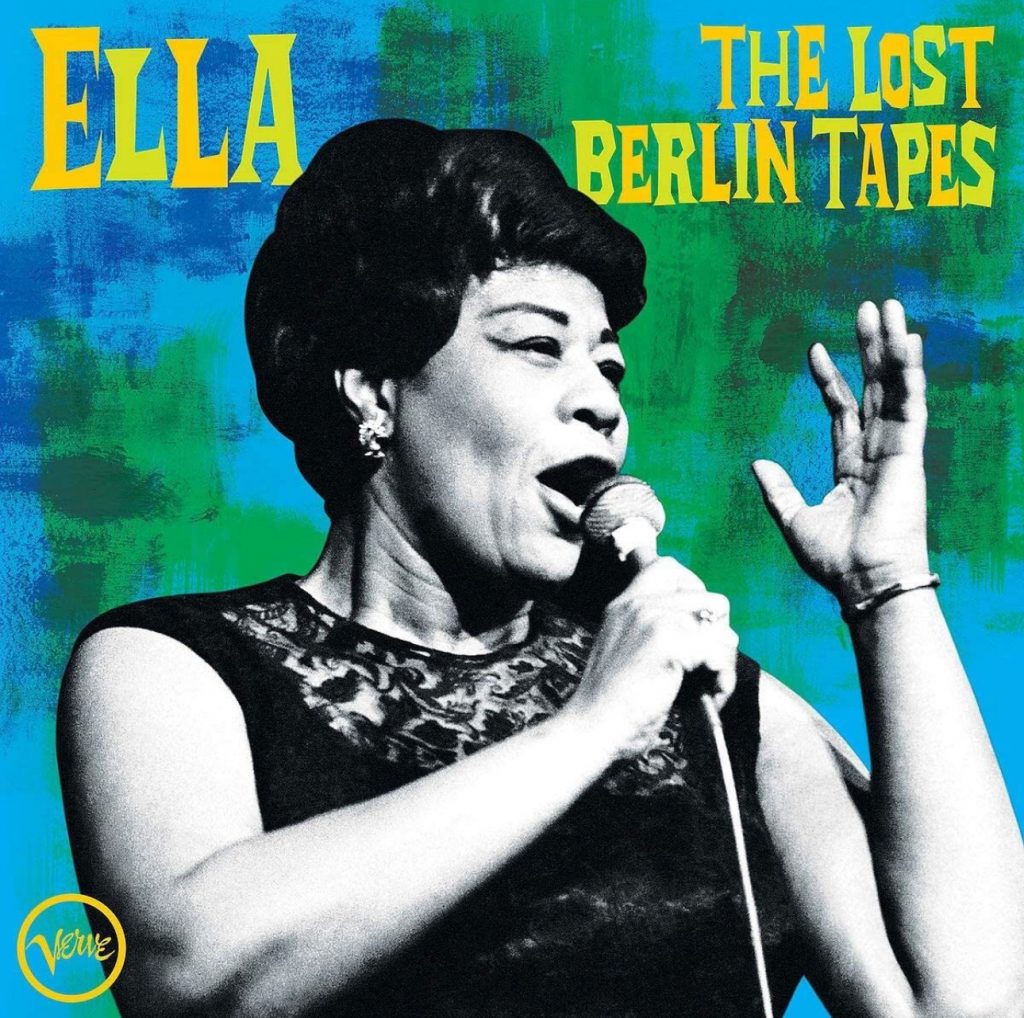

As a lifelong Ella fan, I’m grateful for the continuing deluge of new previously unreleased live Ella recordings that keep getting discovered in the Verve vaults. There’s 2018’s “Ella at Zardi’s” and “Ella at the Shrine,” the 2020 “Ella The Lost Berlin Tapes” and 2022’s “Ella at the Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook.” Did those releases help bolster you as you were writing the biography as these new albums helped to raise her profile?

Tick: Yes, especially the brilliant [2009 4 CD set] “Twelve Nights in Hollywood.” That was a game changer for many people. It served as a kind of canon of her repertoire. And then, thanks to YouTube, there are all of these TV concerts from all over Europe and in Japan that American audiences never saw. I had this enormous treasure trove of material come out during the course of this book.

I finished “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald” on a plane from Philadelphia to Atlanta and when I got to page 436, I was sitting there in my cramped little coach seat crying.

Tick: Good!

You give Ella the last word. Why was that important?

Tick: As a biographer, I believe your subject always has the last word. Always. I emphasized her interviews throughout the book because they were so little known. She made such an impact on me as a way to live one’s life. For me, it was a tribute to that influence that the book had on my own life.

“Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz singer Who Transformed American Song” is in book stores now and available via Amazon.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.