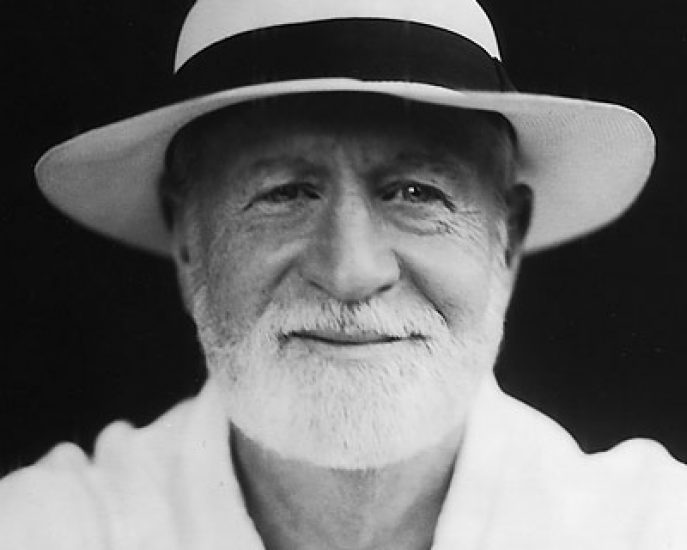

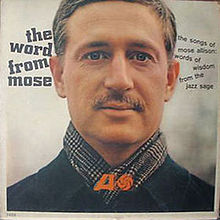

The Final Word From Mose: An Appreciation

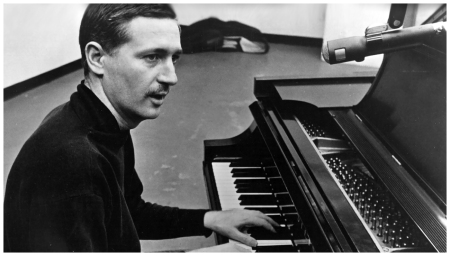

The ritual was always the same. As the final piano chord of the encore drifted out to comingle with the cigarette smoke hanging in the air and the clanging of empty beer glasses being cleared, Mose Allison would pick up the tweed jacket he had draped across the piano at the beginning of his set and slide it back over his slender frame.

The ritual was always the same. As the final piano chord of the encore drifted out to comingle with the cigarette smoke hanging in the air and the clanging of empty beer glasses being cleared, Mose Allison would pick up the tweed jacket he had draped across the piano at the beginning of his set and slide it back over his slender frame.

He’d pause if a fan sitting down front at Blind Willie’s, the venerable blues club in Atlanta’s Virginia-Highland neighborhood, drunkenly thrust an old Atlantic LP at him to sign. But then he’d head to the bar and order a single Rolling Rock beer, a tall boy in a green glass bottle with the painted white lettering. Turns out, the Sage of Tippo, Mississippi was partial to the pride of Latrobe, Pennsylvania.

One night I happened to be sitting on the bar stool next to him, nursing my own bottle of Rolling Rock. He nodded politely in my direction and I thanked him for his set. We struck up a conversation. In less than 10 minutes, the man who was tagged “The William Faulkner of Jazz” managed to weave the novels of Kurt Vonnegut and the trumpet stylings of Louis Armstrong into our conversation. Eventually, I came clean and revealed my occupation to him. I asked if he might agree to a lunch interview the next day to discuss his latest album.

“I’ll be happy to talk to you,” the man I owed tuition money to for my PhD in Irony told me, “but to be perfectly honest, man, I don’t ‘do’ lunch. It’s not really my scene.” Instead, we found ourselves crashed in the lobby of the modestly priced Midtown hotel where he was staying. It was the first of many conversations we would have over the years.

And even though he was recording critically acclaimed albums for Blue Note at the time, the ritual was always the same. I never went through a publicist or a manager or an assistant. Mose didn’t have the time or the money for such things. As he once reflected in his tune “Gettin’ There,” “Limousines and swimming pools/I didn’t get my share/But I’m not downhearted/I am not downhearted/But I’m gettin’ there.”

So I called his house, waited for that familiar Mississippi drawl on the answering machine and left him a message. Or sometimes, his wife Audre would answer and give me the number to where he was staying in whatever city he happened to be playing in.

On Tuesday morning, four days after celebrating his 89th birthday, Mose Allison died at his home in Hilton Head, South Carolina. He left us over 30 studio and live recordings, including his last release, “Mose Allison: American Legend Live in California” recorded in 2006 and released in 2015. His recordings for Prestige, Columbia, Atlantic, Elektra and later, Blue Note were prized by jazz and blues fans but they sold modestly. Mose made more money, thanks to the rock n rollers like The Who, fans who famously included his “Young Man Blues” on the band’s iconic 1970 “Live at Leeds” LP and artists including Van Morrison, Elvis Costello, The Clash and Bonnie Raitt who also covered his work.

Along with Leon Russell (who covered his tune “Smashed!”), Mose served as a music teacher for Atlanta’s most famous piano player, Sir Elton John. Sitting at his kitchen table on the morning after catching a set by Mose at Blind Willie’s, I mentioned attending the show in passing to Sir Elton. His eyes lit up, he rested his chin in his hand and excitedly said, “Tell me everything!”

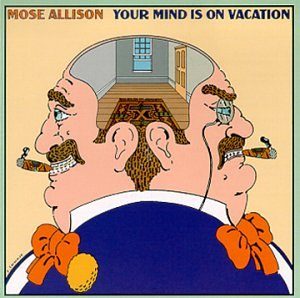

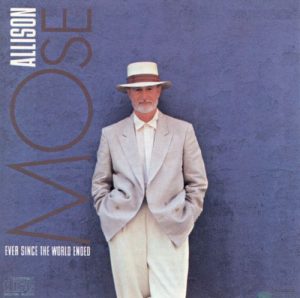

My first introduction to Mose Allison came from my college academic advisor who  was one of the approximately three listeners who regularly tuned into my late-night jazz shift on the campus radio station. Tossing a copy of “Your Mind Is On Vacation,” Allison’s 1976 Atlantic Records release into my hands one afternoon in his office, Dr. Mercier told me, “Here, meet yourself, with a Mississippi Delta accent. You need to play Mose Allison on your show. He’s a gifted jazz pianist. You’ll like him. He’s a wise ass, just like you.” I was still spinning records for collegiate insomniacs in 1987 when Mose released his acclaimed comeback album, “Ever Since The World Ended.” Set against the backdrop of Ronald Reagan’s America, the lyrics were both witty and wicked: “Ever since the world ended/I don’t go out as much/People that I once befriended/Just don’t bother to stay in touch.”

was one of the approximately three listeners who regularly tuned into my late-night jazz shift on the campus radio station. Tossing a copy of “Your Mind Is On Vacation,” Allison’s 1976 Atlantic Records release into my hands one afternoon in his office, Dr. Mercier told me, “Here, meet yourself, with a Mississippi Delta accent. You need to play Mose Allison on your show. He’s a gifted jazz pianist. You’ll like him. He’s a wise ass, just like you.” I was still spinning records for collegiate insomniacs in 1987 when Mose released his acclaimed comeback album, “Ever Since The World Ended.” Set against the backdrop of Ronald Reagan’s America, the lyrics were both witty and wicked: “Ever since the world ended/I don’t go out as much/People that I once befriended/Just don’t bother to stay in touch.”

On Tuesday afternoon as appreciations began emerging from Rolling Stone, NPR, The New York Times and The Guardian, I found myself digging through old interview cassette tapes, wanting to hear Mose’s voice. The first tape I put my hands on was an Allison interview. I dug out an old cassette recorder, pried the corroded batteries out of it, popped in some fresh double AA’s and hit play. To my amazement, I realized I had never published the contents of the interview. In honor of the life and career of jazz and blues legend Mose Allison, here’s the final word from Mose himself.

On his humble beginnings in Tippo, Mississippi:

I learned music from listening to records. I had a cousin who owned some jazz records and a wind up Victrola. There was no electricity at the time. That’s how I first heard Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong. My father was a self-taught stride, I guess you would call it, ragtime pianist and he did it semi-professionally in his younger days. There was always a piano in the house. I took lessons when I was five. It got me familiar with the keyboard.

We got electricity down there when I was about 12 or 13 and then we got jukeboxes in the general store and in the service stations. They had maybe 70 percent country blues on them and the rest would be big band swing. It was just nothing but cotton farms down there in the Delta when I was growing up. I got to hear a lot of what used to be called race records that way from the black sharecroppers.

The first live blues artist I got to see was Sonny Boy Williamson at the Beale Street Auditorium in Memphis. They did a matinee for white people and I got to see him play.”

[amazon_link asins=’B01LT37KO0,B0064WNA4G,B000000ZBE,B0034PHWHW,B00123MAN4,B0181WMHU4,B00KYBBT8C’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’eldredgeatl-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’cfc7fdf4-0ee9-11e9-9f49-69b1faff71e3′]

On Writing His Signature Tune “Your Mind Is On Vacation”:

People always ask about the inspiration for that tune. I was playing a gig at the Showboat in Washington D.C. back in ’58 or ’59 and it was so noisy I couldn’t hear myself up there. That was probably the spur that made me want to write that. I came up with the line ‘Your mind is on vacation and your mouth is working overtime.’ Over the years, I’ve rewritten some of the lines of the song to make it more universal. Finally, I realized I was talking about myself.”

On Inserting Irony and Humor Into Jazz:

On Inserting Irony and Humor Into Jazz:

“Someone once accused me of having an irony hang up but that’s just one of the forms of humor you deal with in your surroundings. I come from that rural Mississippi Depression era thing. There was a lot of irony, stoicism and understatement. I got all that from my childhood. That’s how we got through all that. Country people, farmers, they never said anything straight. There was always innuendo or understatement involved. You were the wise fool.

I’m kind of a deadpan comedian disguised as a piano player. Sometimes if a tune gets too many laughs, I start to feel guilty up there. But it’s all within the context of the music. Some jazz critics say I’m cynical. That’s just something critics will write about you when they don’t want to spend the time to really listen to the songs I’m writing and singing. There’s always a joke in there somewhere. It happens so frequently to me though that it made me go to the dictionary and look it up to make sure I understood the proper definition of the word. The first meaning of ‘cynical’ is ‘distrustful.’ I want to ask those critics, ‘OK, when was the last time you went downtown and left your car unlocked?’ This is the age of cynicism. It’s become necessary. If you’re not cynical these days, you’re in trouble!”

On The Greatest Review He Ever Received:

I’ve been to some jazz concerts that were so grim, man, I couldn’t believe it. The reason I got interested in jazz was that exuberance, you know? Over the years, people who hear you play will come up to you after a job and say something to you that no critic has ever been able to put into words about you in print but it turns out to be more pertinent than anything. A couple of years ago here in Atlanta, this lady came up to me after the gig and said, ‘What I liked about your set was how much you joy you played with. I remember thinking, ‘Man, after doing this for half a century now, somebody finally got it.’ When you listen to Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong and Louis Jordan, the founders of this music, joy is at the root of it. It just comes down to joy.”

Twenty six years ago on the closing track of Side One of his LP “My Backyard,”  Mose Allison penned his own epitaph with the ballad “Was” when he wrote: “When I become was and we become were/Will there be any sign or trace/Of the lovely contour of your face/And will there be anyone around/With essentially my kinda sound?”

Mose Allison penned his own epitaph with the ballad “Was” when he wrote: “When I become was and we become were/Will there be any sign or trace/Of the lovely contour of your face/And will there be anyone around/With essentially my kinda sound?”

The answer is No. You were truly one of a kind, Mose. Sleep well.

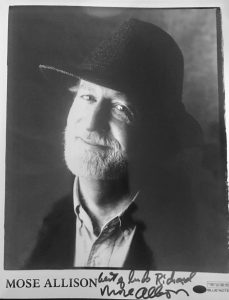

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.