Race, War and the Art of Resigning: Why Paul Hemphill’s Reporting Still Resonates

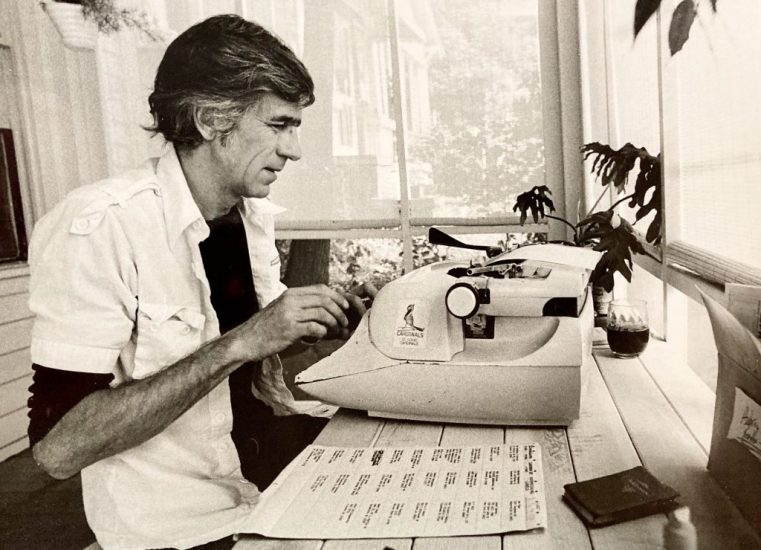

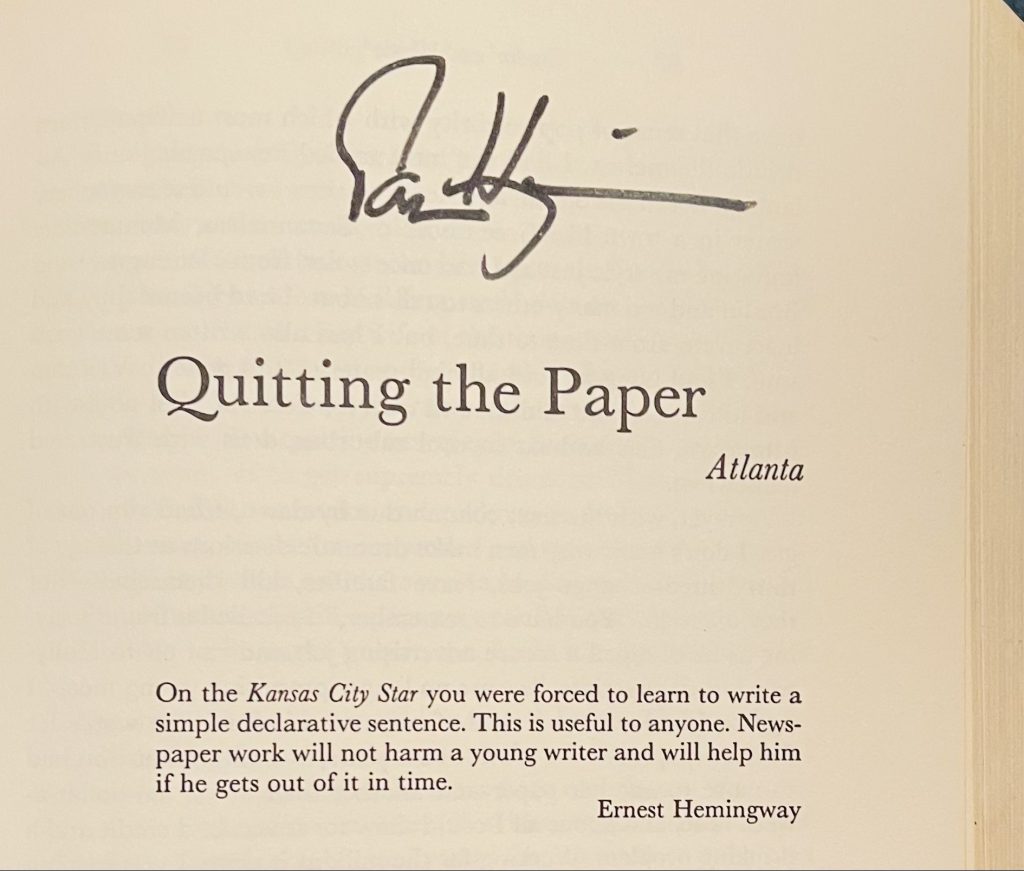

Paul Hemphill didn’t live to witness our current pandemic-propelled “Great Resignation.” And yet, nearly 50 years ago in the pages of Southern Voices magazine, he might have penned the perfect manifesto for the movement. In his iconic essay “Quitting The Paper,” Hemphill recounts the rain splattered evening when, sustained by a series of Beefeater martinis, he walked back to his desk at the Atlanta Journal.

He typed a one-sentence letter, resigning from his $157.03 a week position: “‘Dear Mac, I’m quitting newspapers because I am sick’ — and then I went off to get supremely drunk at Manuel’s Tavern. The next morning broke cold and bleak but, somehow, refreshing. There was a feeling that an exorcism had taken place; that I had successfully negotiated the move from one plateau of my life to another… When I drifted back to the paper to clean out my desk, the old timers glared tight-lipped at one with the audacity to quit. One of the young ones blurted out that it ‘takes a lot of guts to quit like that.’ I said, ‘Christ, it takes a lot of guts to stay. I can steal the kind of money they’re paying me.’”

On Thursday night at the Commerce Club in downtown Atlanta, the former Atlanta Journal columnist, author, novelist and son of the south will be inducted posthumously into the Atlanta Press Club Hall of Fame (he died in 2009 at age 73). It’s an honor that would have pleased Paul, who loved nothing better than to hold court at Manuel’s Tavern on Tuesday nights, unsweetened iced tea in hand, and catch up with his friends, the ink stained wretches still toiling downtown at the big city daily, banging out copy on deadline for the forever looming five-star edition.

Last month, as a friend and an acolyte of his work, I was honored to be interviewed about Paul’s reporting for a video to accompany this week’s induction ceremony. In preparation for the interview, I pulled down many of the 16 books written by Paul over the decades that occupy their own shelf in my home. I discovered that, just as his essay “Quitting The Paper” mirrors the millions of workers who have fled their jobs this year, much of Paul Hemphill’s other work and the topics to which he devoted countless column inches over the decades feel more relevant than ever.

In January, a U.S. president who routinely supplied oxygen to white supremacists left office after his Confederate flag-bearing followers stormed the U.S. Capitol. In August, the human faces of war were horrifyingly brought home when 169 Afghan citizens were blown up while trying to flee Afghanistan as the Taliban resumed control and 13 U.S. troops were killed while trying to extract America from its longest war. A war — and an exit — that was too often reminiscent of Vietnam.

Hemphill’s reporting on race and war (not to mention his life-long allegiance to underdog ball players coming from behind to win it all) could have been published this year.

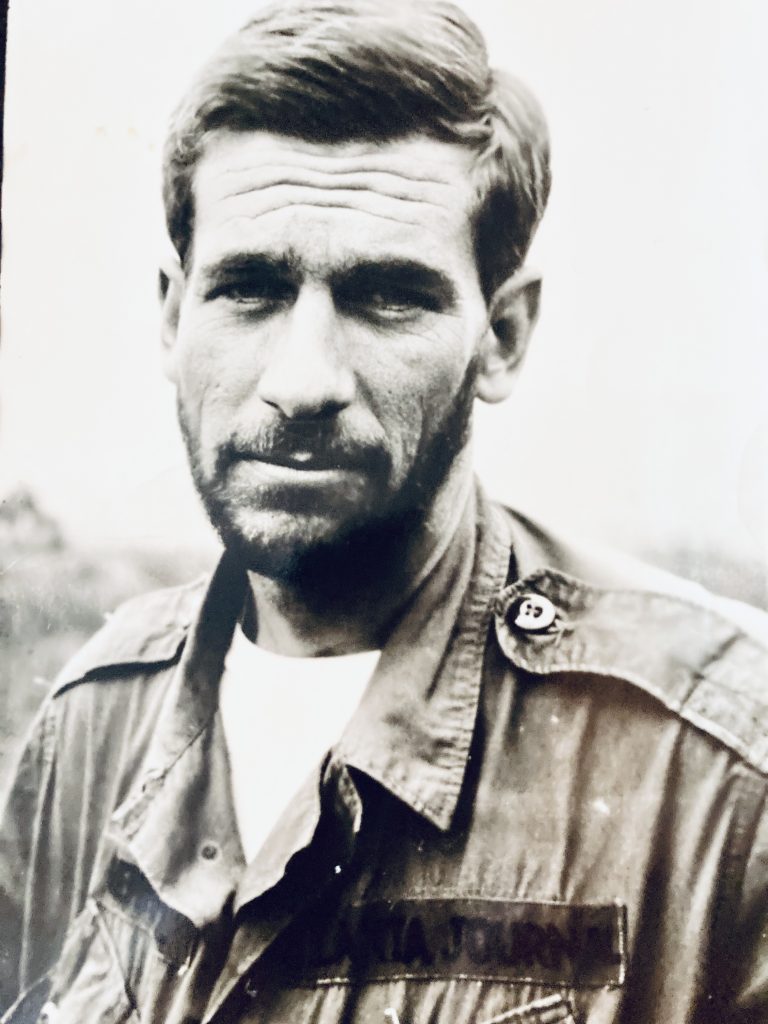

Back in the spring and summer of 1966, the Atlanta Journal sent its star columnist, the self-described “Jimmy Breslin of the South” to Vietnam to bring the war home to readers. From the cockpit of an F-100-F Supersabre jet fighter flying over Saigon, Hemphill wrote, “You never know what it is going to be like. Most of the time it is a matter of working like a computer. You are shown a map and given the coordinates, and somebody out on the flight line loads your bird with napalm and rockets and rounds of bullets, and you have a briefing and get in the air and unload your arsenal when your charts show you are over the proper target, and within two hours you are back home on the ground drinking coffee, and if somebody asks you what the war is like, you do not know, because yours is a computer war.”

Back on the ground in Dak To with the A-Company, 2nd Battalion, 502 Infantry, Hemphill tagged along with Captain Ronald Brown, 26, a former Georgia Tech football player. “Sergeant Lamb looked at the North Vietnamese soldier’s body sprawled out where he had died,” reported Hemphill. “The body smelled like dead fish. ‘Sir?’ he said to Brown. ‘Yes?’ ‘This boy is really gonna smell.’ ‘So?’ ‘It looks like we’re gonna be here awhile.’

‘OK,’ said Brown. ‘Cover him up. Throw some dirt.’ ‘Yessir. Thank you, sir.’”

When Hemphill returned to Atlanta, his ex-Marine managing editor asked him when he had changed his stance on the war from Hawk to Dove. Hemphill replied, “Since the day a kid died in my arms in a bomb crater.”

Over the past four years, millions of Americans have been forced to come to terms with the racist childhood friends, former classmates and neighbors, railing daily against Black Lives Matter marches and kneeling NFL players in their social media feeds, emerging from underground like cicadas. And sometimes, that racism emerged within their own families. The intersections of race, politics, and familial polarization were visited frequently by Paul Hemphill, a Birmingham native, in his work. But perhaps most pointedly in his 1971 New York Times essay, “Me and My Old Man.” Paul later referred to it as both “a favorite piece and the most painful to write.”

“I had been raised by a black maid named Louvenia, never thinking to ask why she took her lunch on the back porch,” he reflected in the piece. “We had a decision to make: fight desegregation or work for it. My old man made it easy for me. During the time I was living under his roof he had seldom felt it necessary to comment on the balance of the races, but the sight of those uppity folks actually demanding service in white Southern restaurants during the early 1960s drove him into a frenzy. This wasn’t my old man. It was somebody else. An autographed 8 by 10 of George Wallace showed up on the family piano. He quit hiring blacks to help him unload his truck — at his age, rolling into his trailer tires that sometimes weighed 500 pounds. He talked about reactivating his father’s old squirrel rifle, which hadn’t been fired in at least 40 years. There had been a time when my old man’s audacious verbosity made him tacky, but now the family was rallying around him as though he were some kind of proletarian prophet. Birmingham became a nice place for me to stay away from.”

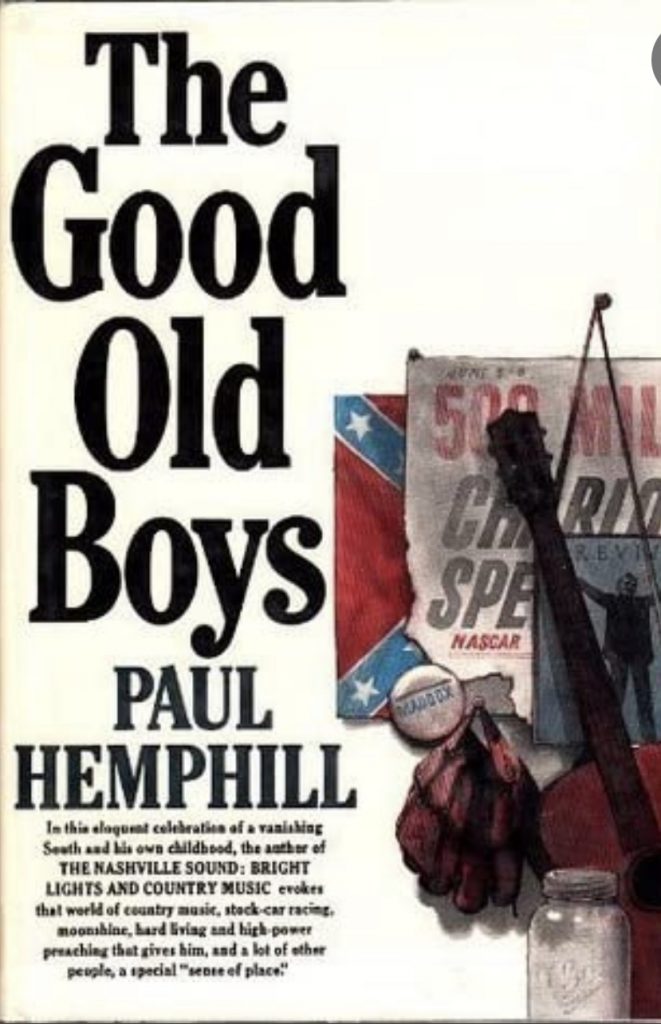

In the introduction to “The Good Old Boys,” a 1974 collection of his journalism covering the south, he wrote, “If you don’t know what a good old boy is, you never will — and he could be a mean son of a bitch: half-educated, vengeful, regressive, sadistic and, by all means, a racist. He could kill a dozen people with bad moonshine and then come out against fluoridation as a Commie plot to poison the water. He could teach his kids hymns on Sunday morning (“Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight…”) and string up the church janitor that evening after prayer meeting.”

Hemphill later recalled the swift reaction to “Me and My Old Man” back home in Birmingham: “My mother ordered my old man to buy up every copy of the Sunday New York Times in which it appeared and burn them in the backyard.” In his 1993 Pulitzer Prize nominated memoir “Leaving Birmingham,” he wrote about what his hometown had become as epitomized by his Hank Williams loving, truck driver dad: “this good man now eaten by racism as though it was cancer.”

In 1971, Hemphill co-wrote “Mayor: Notes on the Sixties” with one of Atlanta’s most influential political leaders, Ivan Allen, Jr., a man who on his first day in office in 1962 ordered all “White” and “Colored” signs removed from city hall. In one of the most riveting chapters in the memoir, titled simply, “Martin Luther King, Jr.,” Allen recalled instinctively but nervously driving with his wife to the King family home in Vine City to be with Mrs. King in the minutes following MLK’s assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968. Later, as other cities across America burned, Allen anxiously paced in his kitchen as his own city prepared for King’s funeral. Thousands of grieving mourners were arriving in Atlanta when the phone rang. On the other end, was a young minister from Central Presbyterian, a huge church across from city hall. “Our board of deacons voted on it and it was unanimous,” the minister informed the mayor. “We’re housing 300 Negro citizens tonight. We’ll provide meals for several thousands during the march when they pass by the church and we’ll have living quarters for as many as we can take. But we’re going to need 600 blankets.”

Recalled Allen of what was going through his mind at that moment: “So this is how Atlanta was going to react. In the back of my mind all along had been great fears that the major factor in whether Atlanta was going to have serious trouble or not was not with the black people but with white racists. But here was a young Presbyterian minister saying his church was opening its doors to Negro visitors. Later in the day, hundreds of other white churches in the city made similar announcements. It took me only a minute to call Third Army headquarters and get six hundred blankets.”

Like his writings on race and war that continue to resonate in these times, Paul’s most famous essay, “Quitting The Paper” offers a blueprint for today’s working stiffs who have the audacity to reimagine their careers and reassess the quality of their lives. Recalling the day after his own Great Resignation from the Atlanta Journal, Hemphill wrote, “By noon, I had an agent in New York, by two o’clock I had a bank loan of $2,500, by five o’clock I had a modest office above a tire re-capping place and by bedtime I had enough insurance — disability, hospitalization, life — to take care of a Marine platoon in combat.”

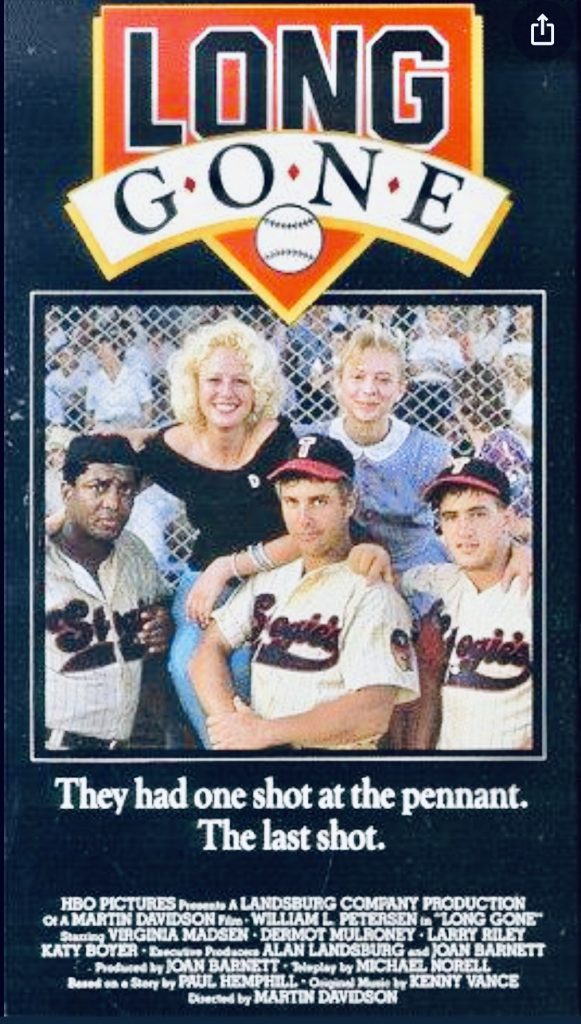

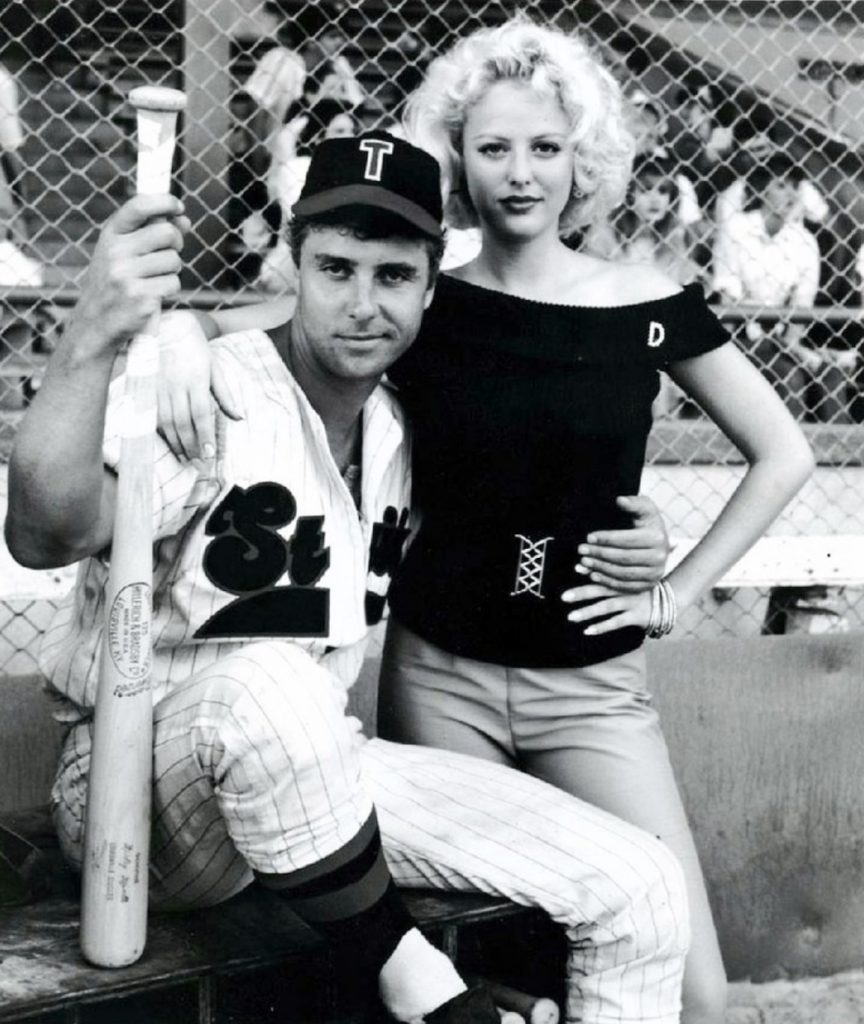

Shortly thereafter, he inked a deal with Simon & Schuster to embed himself for months inside the home of country music to write “The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music,” the first serious look at the American art form, a debut later lauded by the New York Times. Then came the offer to collaborate with Ivan Allen, Jr. and “Long Gone,” the 1979 baseball novel inspired by his adventures growing up in the minor leagues. Hollywood would later cut Hemphill a check for the screen rights to the book when HBO turned it into a 1987 film starring William Petersen and Virginia Madsen. For baseball fans, the movie has become a cult classic.

In all, Hemphill authored 16 books over a half century. And while he was pleased whenever someone told him “Quitting the Paper” had inspired them to do some career housecleaning of their own, he was quick to caution others considering taking the leap. “All of a sudden there is no Big Daddy to give you a paid vacation, pay your phone bill for business calls, let you take a day off, refund your business expenses, cover your hospital bills or pay your postage,” he warned in the piece. When a younger Journal colleague offered to quit in solidarity, Hemphill told him, “It isn’t your turn yet.”

I’m familiar with that particular piece of advice. A couple of decades back, frustrated with my own career trajectory at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, I applied for a newspaper columnist job in Las Vegas. I flew out to Nevada, interviewed and ended up landing the job.

But the reality of leaving my adoptive hometown and a city I loved covering nagged at me. “You’ll know when it’s your time to quit,” Paul told me. Around that same time, there was a release party at Manuel’s Tavern for Paul’s latest book, a novel titled “Nobody’s Hero.” In my copy, his inscription was short and sweet: “Don’t Leave. We need you.” So, I didn’t. It ended up being some of the most valuable advice I’ve ever received. And Paul was right. When it was time for me to move on, I knew.

Thanks in no small part to that advice, you’re reading these words on a digital platform I started, a platform dedicated to the city’s stories I want to cover. As one of the many reporters whose work he helped make better by showing us how to do the job, I’m thrilled that our mentor, the lanky scribbler in the faded jeans, the Braves cap and broken in boots has been selected by his peers for the 2021 Atlanta Press Club Hall of Fame.

Assessing his legacy after Paul’s passing in 2009, actress Virginia Madsen (who memorably portrayed his tough cookie heroine Dixie Lee Box in the film adaptation of “Long Gone”), sent a letter to his friends and family. It was read at a special screening of the film at Manuel’s Tavern. “A great writer can never truly die,” she stated to the assembled. “A great writer can only continue to live on, each time his work is experienced. Each time his words flow again, his spirit flies back to us and serves us again with words that are truly a feast.”

Thank you, Paul for leaving us such an enduring literary legacy, a truly bountiful feast that continues to nourish us all, each time we open one of your books.

Above photos of Paul Hemphill courtesy of Susan Percy

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.