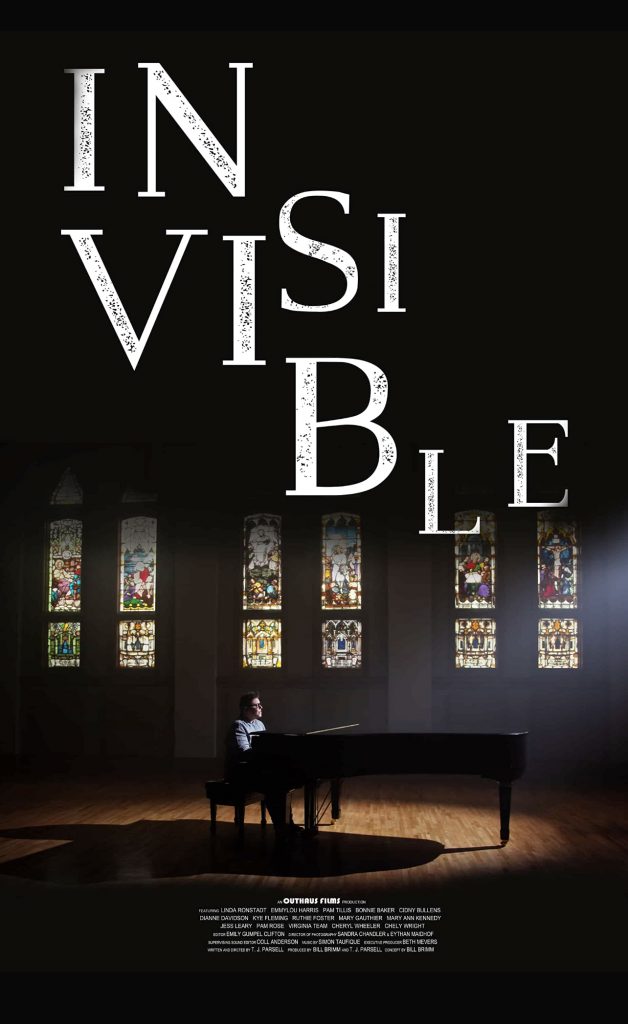

‘Invisible’: An Out on Film Q&A With the Cast of the Powerful New Gay Women in Nashville Doc

Director T.J. Parsell’s emotional and eye-opening new documentary “Invisible” finally lifts the veil on a group of gay women songwriters responsible for some of Nashville’s biggest hits over the last 50 years. Successful songwriters who, due to their sexual orientation in the male dominated country music industry, had to remain invisible in order to make a living.

Dianne Davidson, toured with Linda Ronstadt in the early 1970s but her solo singing career came to a screeching halt in 1974 when she included a same-sex love song on her fourth album recorded in Nashville. Closeted singer-songwriter Kye Fleming co-wrote hits like “Sleeping Single in a Double Bed” for Barbara Mandrell along with hits for Charley Pride, Willie Nelson and Ronnie Milsap while Virginia Team, as art director for CBS Records — one of the few out lesbians at the time in the 1970s — was working with the likes of Johnny Cash. In that same decade, Cindy Bullens was touring with Elton John before her androgynous rocker look and sound sidelined her career. In 2011, the singer-songwriter transitioned to Cidny Bullens and wrote a new album based on his experiences. Bonnie Baker, meanwhile, has written hits for Reba McEntire, Hunter Hayes, Sara Evans, SheDaisy, Rascal Flatts and Chad Brock.

Not everyone was willing to stay in the shadows. Out and proud performer Ruthie Foster puts it succinctly in “Invisible”: “If you have a problem with it, I guess you’re not listening to Ruthie Foster and I’m cool with that.”

Now, thanks to the illuminating “Invisible,” their successful professional lives on Nashville’s Music Row are merged with the personal lives they were forced to keep under wraps in order to work in the still-homophobic country music industry. The doc also tracks the career trajectory of Chely Wright, who was on top of the country charts in the 1990s until she came out on “Today” in 2010 and outed herself on-air to Oprah Winfrey. Sadly, she hasn’t been on country radio since.

The powerful doc (which won the Best Documentary audience award at San Francisco’s 2021 Frameline LGBTQ film festival) screened Saturday night at Atlanta’s Out on Film and is available to stream via the Out on Film website until Oct. 10.

Following the film’s enthusiastically received Atlanta premiere September 25 at Landmark Midtown Art Cinema, producer Bill Brimm, director Parsell, along with Baker, Bullens and Davidson held a post-screening Q&A with the audience and Eldredge ATL editor-in-chief Rich Eldredge.

The following is an edited version of that Q&A.

Rich Eldredge: Bill, I want to start with you because the idea for the film was yours. Why did you want to make this doc?

Bill Brimm: A lot of these women have been my friends for many years. I knew their stories and I thought a film like this would be a great way of telling their stories. I talked to T.J. about it and three weeks later we were interviewing Mary Gauthier.

Eldredge: T.J., There’s a lot of emotional intimacy in this film. How did you get these people to trust you and to open up on camera?

TJ Parsell: From our very first interview with Mary Gauthier, Bill and I both just kind of sat back and were blown away by how vulnerable they were willing to be and how open they were. They had a story that obviously needed to be told. Our toughest job was creating the safe space for them so that could happen.

Eldredge: Dianne, you’ve described T.J. as someone who “finds a respectful way to get you to bear your soul.” How did he do that?

Dianne Davidson: You don’t even realize he was doing it until you’re through and you realize you’ve cried and you’ve rended your garments [audience laughs] and you’ve exposed things about yourself that you didn’t realize had happened to you. That’s how deep it is. TJ always had the ability to create that space for you, which is what a good director or record producer does. You create the environment and then allow the creative people to explore and share.

Eldredge: Bonnie, you bookend the film at that piano in Ocean Way recording studios, a converted church in Nashville. The film tracks the autobiographical songs that you create and you perform your powerful song “Dry County” at the end of the film. As a successful songwriter in Nashville, did you have any hesitancy about putting so much of yourself out there?

Bonnie Baker: T.J., Bill and I sat down for the first interview and literally, in the middle of the interview, something cracked. I had never talked about this out loud. I had always just wanted to be a songwriter, not a gay songwriter, a songwriter. It was always about writing songs for other people. It was really hard for me to be out in public. Even standing here, answering questions, is not my easy place. Every showing of this I want to tell people that it was hard for me so if it’s hard for you or if you have kids and it’s hard for them, there are those of us who have fought through it. We’re here.

Eldredge: Cid, everyone who has seen this film knows what a bad ass you are. But you were a bad ass in 1979 on “American Bandstand” with Dick Clark, too.

Cidny Bullens: Dick Clark is a dick [audience laughs].

Eldredge: Dick Clark manages to be misogynistic twice in one movie. You came out of the gate strong with a great debut record, you’re on “Bandstand” but you were an androgynous artist and it ended up hurting your career as a woman. David Bowie, in contrast, used it to sell records. Why couldn’t Cindy Bullens?

Cidny Bullens: Well, we don’t have all night. [audience laughs]. There was a bias against women. I had multiple record execs say to me, “We already have a woman — as in one — on our label. We don’t need another one.” It was doubly hard. It never crossed my mind that being a woman would impair my talent, my trajectory. I also made my own choices and eventually, I just said ‘fuck it.’ It was just road block after road block.

Eldredge: Your 1979 debut album “Desire Wire” is on Spotify. It almost feels like Cindy is singing the opening track, “Survivor” to the future you.

Cidny Bullens: That’s true. My first hit single was called “Survivor” except back then, I was singing to a guy because that’s what they expected female artists to sing about. and it’s true, I am a survivor and I think that’s true of everyone standing up here. We’re all survivors.

Eldredge: Dianne, let’s discuss that Linda Ronstadt scene. Every fan knows she’s been struggling with Parkinson’s and has lost the ability to sing. You sit on her couch with your guitar and discuss touring together in the early 1970s and you begin playing a song you two used to do and she begins harmonizing with you. What was going your mind?

Dianne Davidson: I didn’t even remember that we had that song in the show. I was just playing songs she wanted to hear and all of a sudden she began singing along. I was overwhelmed. It took me back to when we first met, back when we were both kids. I was grateful she felt comfortable enough with me to do that. It meant the world to me.

T.J. Parsell: Usually, when we screen the film, there’s a collective gasp in the audience when she starts singing. But when you’re filming, you can’t make any noise because the microphones are so sensitive. There was that same gasp in the room with us but we had to stifle it. I don’t think there was a dry eye in the room. We were all crying. I was watching the two camera men, their viewfinders were misting up and the poor sound guy is holding the boom and he had tears coming down his face. It was a really powerful moment. Dianne and I had the opportunity to screen the film for Linda the night before it premiered [at Frameline] in San Francisco and that was really powerful as well.

Eldredge: As a gay boy who wore out my cassette copy of Kennedy Rose’s debut album “Hai Ku” in 1989, I’m eternally grateful to you ,T.J., for spotlighting them in the film. Bonnie, what was it like for you, as a fan, to have them sing back-up on your song “Dry County” and to have that moment at the end of the film?

Bonnie Baker: They are two of the loveliest human beings. Mary Ann Kennedy and Pam Rose have integrity and talent and no ego. They always had their arms around my shoulders saying, ‘What can we do to help?’ We had a cellist for the end of the film and T.J. came up with the idea to have them do bgv’s [background vocals]. I said, ‘They’re not going to drive into Nashville and spend the day recording a song.’ And T.J. called back and said, ‘They’re both in.’ It was a beautiful moment and they’ve become friends of mine. They truly are as kind as you see in the film.

T.J. Parsell: Bonnie is very stoic and very grounded so you never know if she’s into an idea based on her reactions, which are often one word. I remember saying to her, “We found this amazing studio that looks like a church.” And she said, “OK.” And I’m seeing cello, do you think we can work a cello into this? “Well, I’d have to write it but OK.” And I’m thinking of asking Kennedy Rose to sing back-ups and Bonnie said, “Get the FUCK out of here!” [audience laughs and applauds].

Eldredge: T.J., that pizza dinner scene with Kennedy Rose and singer-songwriter Cheryl Wheeler and [veteran record company art director] Virginia Team not only sharing their coming out stories but singing together on Cheryl’s song “Driving Home” is just incredible. Was that another night when you were thinking, “Is this really happening?”

T.J. Parsell: Probably every filmmaker sitting in the audience knows that you sometimes put stuff together and hope it works. We kept the wine flowing that night. [audience laughs]. One of the P.A.’s jobs was to discreetly keep filling their glasses. And Virginia Team got wise to it and she started tapping her glass when she wanted a refill. [audience laughs]. Bill and I were in the other room watching the monitor, hoping they would forget we were there. And then the magic happened. It was lightning in a bottle.

Eldredge: What is remarkable about this film is that it proved inspirational for the people who participated in it. Dianne, you have a new album out, right?

Dianne Davidson: Yes, it’s called ‘Paragon.” And that album from the 1970s that’s referenced in the doc, I’ve also released that as “1974,” and it includes the [same-sex love song] that got me kicked out of the club. It’s been pretty incredible. The film has been extremely important to me. Life has been a struggle but I know these people have my back no matter what. The biggest thing for me in this film is the relationships that have come out of it.

Eldredge: Cid, tell us about your latest album, “Walking Though This World.”

Cidny Bullens: It’s my first record as Cidny since my transition. I like to say I make a record every 10 years whether I need to or not. It’s a reflection on my transition. There are also a couple of love songs to my wife. I’ve known pretty much everybody in the film for 30 years except for Dianne, Bonnie and Chely Wright. Every time I see this film, I love these people more. The film has been a great gift but the greatest gift is the camaraderie and the friendships that have developed from the film.

Bonnie Baker: Getting to meet Virginia Team and having her text me all kinds of fun, nasty, dirty, awesome things is one of the greatest joys of my life, along with meeting Mary Ann and Pam, Kennedy Rose and all of these people that are a part of the film. I felt like I had lived in this little compartment in Nashville, trying to be good, trying to keep quiet and keep my head down. And all of a sudden to have this community love me for exactly who I am? That’s been the biggest gift.

Eldredge: It’s often frustrating watching this film because as the viewer we’re thinking, ‘It’s 2021, how the fuck is Nashville still operating this way?’ But then again, straight men are still in charge. Bill, are you hopeful this film can create change?

Bill Brimm: I think we’re already starting to see some changes in the business. There are a couple of country artists who are out now. They’re not on TV talking about it but everyone knows and they’re able to work.

T.J. Parsell: I would like to say I’m hopeful that the film will make a difference. But the reception in Nashville so far has been a little underwhelming. We got into the Nashville Film Festival but they wanted to put us in the basement of Belmont University on a Monday. The press has been slow to come around. We’re going to keep pushing. But I think we still have a long way to go. There are a number of artists in Nashville who are gay and everybody knows it — everybody except their audience. Even Katie Pruitt, whose gorgeous song you hear at the end of the film, was slated to be in the film. We were excited about it and she was excited about it. But then her middle-aged, heterosexual manager talked her out of it and said, “Look, you are this close to breaking through. Wait until you’re on the other side and then maybe.” Given what we’ve learned about Nashville while making this film, I’m not sure I blame or disagree with him or her.

But I’m happy that her song runs in the end credits of the film because it’s a beautiful juxtaposition to Dianne’s song and story. Here is a young gay artist whose love song to her lover ended up launching her career.

The last thing I want to say is this: all of the young artists coming up now hold an enormous amount of gratitude to the women in this film because they are heroes.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.