That Time Black Panther Came To Georgia And Kicked Ku Klux Klan Ass!

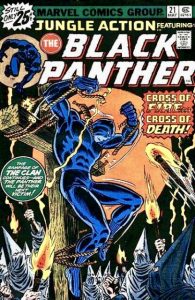

As a 12-year-old in 1976, Tony Cade can still remember walking into Paper Chase, the comics shop across from the MARTA train station in Decatur and seeing the cover of Jungle Action Featuring Black Panther No. 21. The climax of the epic five-issue story arc of “The Panther Versus The Klan” involved Black Panther (aka T’Challa, King of the African nation of Wakanda) battling the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia. The cover featured Marvel Comics’ first black superhero breaking his bonds tied atop a wooden cross surrounded by a mob of torch-bearing klansmen. Inside, the gripping images created by Marvel artist Billy Graham, one of the company’s first black artists, are some of the grittiest in Marvel Comics history.

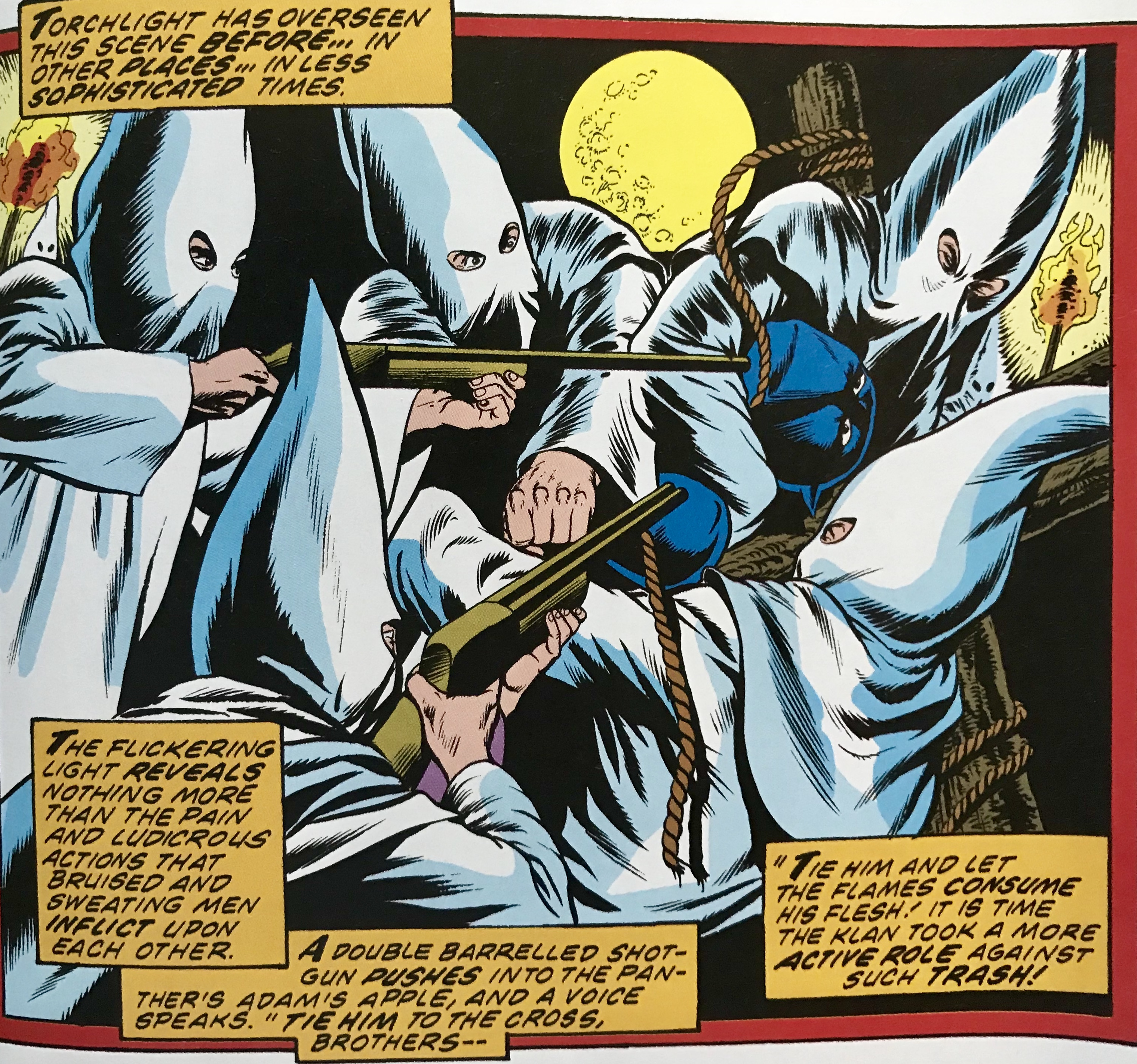

As the issue opens, Black Panther is being burned alive on a cross, surrounded by white supremacists. Writer Don McGregor opens the terrifying tale thusly: “He is not a symbolic Christ. Forget about turning his flesh and blood into some esoteric allusion to the persecution of contemporary man. This is the Black Panther King of the Wakandas. And He is made of flesh and blood. And the flames which consume the cross and his body prove his humanity. And the death-watchers, dressed in white robes revel at his torment. And desire his death!”

Flipping through the sequence again 42 years later inside Challenges Games and Comics, the shop he owns and operates at North DeKalb Mall, Cade still marvels at the power of the story.

“These are classic images,” Cade says, paging through Graham’s gorgeously gruesome artwork. “During that time period in the 1970s as a young black kid growing up in the south, the KKK was very real to me. The KKK was something to be feared. They were hosting cross burnings on top of Stone Mountain. It was real and it was terrifying. So when you had a character like Black Panther taking it to them, you were like, ‘Hell yeah!’ Even a comic book character doing what needs to be done helped to calm some of your rage. It allowed you to function in the world without being worried all the time.”

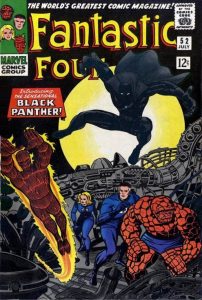

Like a generation of comic book readers, Cade discovered Black Panther when the character, created by Marvel Comics icons Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, debuted for a two-issue guest starring stint in his favorite comic, Fantastic Four No. 52 and 53 in 1966 (blessedly, Lee and Kirby opted not to use the first name they came up with their new creation — Coal Tiger). After luring the crime-fighting quadrangle to Wakanda with a gift of a magnetic wave space ship, Black Panther proceeded to fight — and defeat the Fantastic Four. By the early 1970s, the character was fighting beside Captain America as one of The Avengers and in 1973, he landed his first solo run as the star of Jungle Action Featuring Black Panther, an old Marvel title writer Don McGregor refurbished for the African superhero.

[amazon_link asins=’B079NKRK66,B07CSKDGFF,B079F9D91N,B07M59VXNV,B005KF4T9I,1302901907,1302915428′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’eldredgeatl-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’68fc3ecf-0ee2-11e9-9890-99080b7c81fb’]

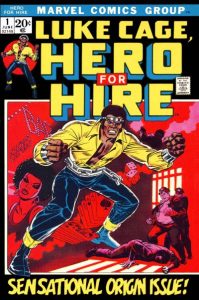

In 1972, Marvel added a second black superhero with Luke Cage, Hero For Hire, a crime fighter based in Harlem. At 25 cents each, Cade scoured his neighborhood for pop bottles to return to grocery stores for the 10-cent deposit. Three pop bottles equaled a new title to add to his growing collection.

In 1972, Marvel added a second black superhero with Luke Cage, Hero For Hire, a crime fighter based in Harlem. At 25 cents each, Cade scoured his neighborhood for pop bottles to return to grocery stores for the 10-cent deposit. Three pop bottles equaled a new title to add to his growing collection.

“As people like to say now, representation matters,” says Cade. “My family was one of the first black families to move into the Greenbriar neighborhood. I was drawn to Black Panther and Luke Cage because they looked like me. What I liked about Marvel was even though these stories were being written by white guys, they didn’t go overboard with stereotypes. They tried to tell meaningful stories. Because these characters looked like me, I wanted the stories to be done well. It mattered that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, when they created Black Panther, they created a superhero who was very intelligent. He was someone who could act and think and do what was necessary. He was protecting his people in a technologically sophisticated African country. That all mattered to me.”

Black Panther writer Don MeGregor is widely credited with creating the first graphic novel with his 13-issue, two-year Jungle Action epic tale “Panther’s Rage.” But his ambitious “Panther Versus the Klan” follow up would also spell the end of Jungle Action.

Tom Heintjes, the editor and publisher of the Atlanta-based comics journal Hogan’s Alley saw Jungle Action’s final trail-blazing continuity as a risky endeavor. “Back then, comics were a much more mainstream form of entertainment so this was a very gutsy story to publish,” reflects Heintjes. “This was the end of the Jungle Action title and they went out on a high note. They threw everything they had into that klan story.”

But re-reading the storyline in 2018, Heintjes has, well, a few issues with the issues. “The material perhaps hasn’t aged so well,” he allows. “These were some young, very earnest white guys. It’s a little embarrassing to read with modern eyes. It’s very heavy-handed, even if well-intentioned.”

But for Heintjes, Billy Graham’s gut-punching artwork is another matter. “Here’s a guy who, like most Marvel artists, was getting a modest per-page rate wage and yet, his artwork is so powerful. It’s authentic, it’s cathartic, it’s a profound artistic experience. As a reader, the art leaps off the page. You feel it.”

As a former Thousand Oaks, Calif. neighbor of Black Panther co-creator artist Jack Kirby (who would write, edit and draw the relaunch of the character when he got his own eponymous comic book in 1977), Heintjes says the Wakandan king is just one example of how Kirby lived his life outside the panels of his comic book creations.

“Jack was egalitarian,” says Heintjes. “He believed that everyone deserved to be treated equally and fairly. He valued everyone. So it’s not surprising that he helped to create Black Panther and went on to create [Captain America’s African-American crime-fighting partner] the Falcon. Even in the same 1966 issue of Fantastic Four where Black Panther is first introduced, there’s a Native American character, Wyatt Wingfoot fighting alongside the Fantastic Four. Jack and Stan Lee were both Jewish New Yorkers. Neither went by his birth name professionally [Jack Kirby was born Jacob Kurtzberg and Stan Lee was born Stanley Martin Lieber]. They knew what it felt like to be an outsider and their stories and characters reflected that. It’s safe to say if Jack Kirby were alive today, he’d be the first person in his neighborhood with a Black Lives Matter sign on his front lawn.”

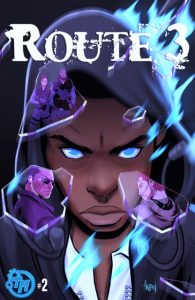

For Khari Sampson, the editor and letterer on the Route 3 comic book series published by Tony Cade’s Atlanta-based Terminus Media, the character and adventures of Black Panther made an indelible imprint on his creative life. He sees director Ryan Coogler’s new big budget blockbuster feature film adaptation, “Black Panther” debuting in theaters this weekend as a way to empower a whole new generation of young people. Sampson attended a press screening of the film this week to write a review for the Gwinnett Daily Post.

“Not to put too fine a point on it, but this movie changes everything,” says Sampson. “For young people to see a cast like this where we’re not the tokens, where we’re not the first people to die? If you’re brown or black and you’re looking up on a movie screen and seeing yourself as a central character driving the story? That’s a game-changer.”

These days, Sampson has his name on the front cover of Route 3, a comic book series starring Sean

Anderson, a fictitious Stone Mountain 16-year-old kid of color just looking to survive high school and ends up becoming a superhero fighting the country’s war on terror. Sampson is hoping Sean does for kids today what Black Panther did for him as a young comics fan, who was inspired to first write and draw his own comic book creations back in the 1980s.

But when Sampson transferred his creations into a fresh sketch book, he noticed something about his work: “I got to about page 12 of my retrospective before I saw my first black character. They were all white. As a comic creator, I had to ask myself why. It’s because I wanted to be Luke Skywalker like all the other kids. Most of my favorite comic book heroes were white because that’s what was out there to read. I realized I had to darken up my cast, I needed to create more characters of color within my own work. It’s one of the reasons I’m proud to have my name on and be a part of the Route 3 comic.”

Back in his Challenges Games and Comics shop, Route 3’s publisher Tony Cade is discussing Black Panther’s 52-year cultural impact on comics fans. His shop has been a safe haven for comics and gaming nerds for so long now, some of his original customers have grown up to become police officers or to create their own entrepreneurial endeavors. It’s why Cade sponsored two advance screenings of “Black Panther” this week at Atlantic Station and North DeKalb Mall.

“This is a cultural moment,” Cade says. “You have an ensemble black cast with a proven black director and a powerhouse like Disney financially backing it. It’s not a comedy or a gangster flick. We’re not shooting at each other or selling drugs to each other. It’s an opportunity for us to see ourselves on screen in a whole new way. And if people win awards for this film, they’ll win them for playing something other than a slave. That all matters. For years, at all the comics conventions, black people have been telling the folks who run Marvel Studios, ‘If you give us a good ‘Black Panther’ movie, we’ll support it with our dollars. Look at the advance ticket sales of this thing. They’re through the roof. There’s a reason Netflix’s [servers went down due to high user volume] the weekend ‘Luke Cage’ premiered [in 2016]. Hollywood should get ready!”

But even now as a comic book publisher himself, putting superheroes of color out into the world while running a business where a second generation of customers discover a safe space and find community with other comics fans, Tony Cade still has a few iconic holes in his personal comic book collection.

Sure, he’s got mint copies of Fantastic Four No. 52 and 53 featuring the debut of Black Panther, Luke Cage Hero For Hire No. 1 and even DC Comics’ Black Lightning No. 1, but a few issues remain elusive.

He points to the cover of Jungle Action No. 21 from May 1976 with his favorite superhero breaking the bonds of that burning cross with the menacing torch-bearing klansmen below him.

“It’s an issue that’s difficult to find in mint condition,” Cade concedes. “It’s hard to find one out there in good shape because those issues were so well read over and over and over again. It was one of those you loaned to your friends to read. The pages got creased and the covers got bent up because people were reading them. For me, that’s the secret of a great comic book. Those are the stories that stay with you.”

“The Panther VS The Klan!” comics are collected along with the entire “Panther’s Rage” continuity in the new “Marvel Epic Collection: Black Panther,” Marvel Books).

Route 3, created by Robert Jeffrey II, is available at Challenges Games and Comics inside North DeKalb Mall or digitally at terminus media.com.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.

Me and ‘Black Panther’: part 3 — Blackest film ever? | Bridge Over Troubled Opinions

February 26, 2019 @ 12:15 pm

[…] old Atlanta Journal-Constitution colleague Richard Eldredge, founder and editor of EldredgeATL.com, came calling to get my take (along with others’) on “Black Panther” in the leadup to the film’s release in February 2018. But I really did not quite understand […]