Dancing On The Tables: A Celebration Of The Athens-Atlanta Music Scene, Starring The B-52’s, The Fans, The Brains, Glenn Phillips and some act named R.E.M.!

Note From Eldredge ATL guest writer Maureen McLaughlin, the B-52’s first manager: I probably wouldn’t have agreed to write this article except that Eldredge ATL July Guest Editor Vanessa Briscoe Hay pitched an appealing idea — contact people from the Atlanta and Athens music scenes of the 1970s and 1980s and ask them three questions. Whatever you get from them goes in the article. No herding of cats, no follow-up reminders, no begging and pleading allowed.

After spending the past five years of my life working on projects that involved boatloads of goading and prodding, how could I resist participating in this experiment? I sent out a copious amount of emails and got back five responses. The thing is, my five correspondents perfectly exemplify the Atlanta/Athens music connection. Keith Bennett was one of the University of Georgia art students who lived in the vortex of the Athens creative scene, a crumbling ante-bellum mansion belonging to UGA Professor Jim Herbert. Darryl Rhoades was the flamboyant and ferociously funny frontman for Darryl Rhoades and the Hahavishnu Orchestra, and Kevin Dunn was the guitarist for Atlanta band The Fans. Doreen Cochran was band coordinator for The Brains, and Glenn Phillips was guitarist in The Hampton Grease Band. From their stories and experiences, you will be able to see how the paths of the two cities intertwined.

I was a product of the interweaving of Athens and Atlanta, having grown up in both towns and participated in the music scenes in both places. Let’s start with me and move on from there to Keith Bennett and beyond. Thanks to Vanessa, we have also been granted permission to publish some drawings of the era from influential UGA art professor Robert Croker as well. Enjoy!

Maureen McLaughlin

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both):

Both. Definitely both.

2. Your Connection To The Music Scene:

I was the B-52’s first manager. I also did a lot of networking between bands in Athens and Atlanta and other places as well, getting the Fans their first gig in NYC, shortly followed by doing the same for the B’s. Before that, I was going to concerts at the Twelfth Gate in Atlanta and in Piedmont Park.

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

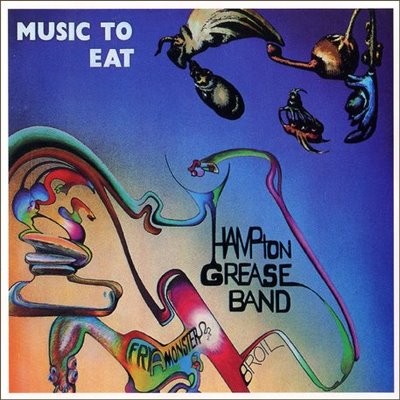

I grew up in Atlanta and went to high school in the Sixties. As soon as I got my driver’s license, my mother turned the family car over to me. The deal was that I had to chauffeur my sisters and brother during the day, and at night I could do whatever I wanted. Having that freedom enabled me to start hanging out at the Twelfth Gate coffeehouse in Atlanta, an experience that changed my life. The Twelfth Gate was started by Grace United Methodist Church to minister to the unchurched street kids hanging out on the Strip. It became a mecca for jazz and blues musicians who liked to play there because the audiences were fantastic, and it was one of the only truly integrated places in Atlanta where they could play. The club was in an old house, and the stage was in a corner of the dining room. The audience crammed into every nook and cranny of the first floor, jamming into the living room and kitchen, and spilling out on to the front porch. The house band was (or might as well have been) The Hampton Grease Band, a brilliant group of musicians who made the panes rattle in the windows with their wild style of jazz. I also saw McCoy Tyner there, and Larry Coryell, Pat Metheny, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGee, Big Mama Thornton, John McLaughlin and many other incredible musicians, including my favorite, Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Between sets, the musicians hung out with the audience, and since many of the players were on a circuit where they came through town regularly, it was not hard for the audience to become friends with the musicians.

I also spent many afternoons in Piedmont Park listening to music. Many groups would play shows for money on Friday and Saturday nights, and then show up at Piedmont Park to spend Sunday afternoons making music. An incredible assortment of people came through there. The Allman Brothers were at Piedmont so, so many times that their music saturated my soul. It would not be unusual to find Edgar and Johnny Winter, Spirit or the Grateful Dead playing there. Something was always going on, and it was all pretty wonderful.

When I moved to Athens to go to UGA, I got on the Concert Committee for the Student Government, which was an excellent way to get Atlanta bands to Athens. I also helped to start a coffeehouse in Memorial Hall at UGA, but it got shut down because we were dancing on the tables and playing inappropriate music, according to someone in the administration. All during my college years and afterwards, I ran a rut in the road from Athens to Atlanta, going to shows at Rose’s Cantina, 688, the Great Southeast Music Hall and a number of other Atlanta venues.

4. What are you doing in music now?

I have been a part of the stage crew for our local music festival, AthFest, for the past 14 years. I get local people to announce the bands on the two outdoor stages. I am also slowly doing the research to write a book about Pylon.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

After the Twelfth Gate closed, many of the musicians who played there began playing at the Great Southeast Music Hall. The two venues could not have been more different. While the Twelfth Gate had a bunch of random second-hand chairs along with sofas and armchairs crammed into a tiny space, the Music Hall was a proper theater with a large stage and plenty of room for several hundred people.

The first time Rahsaan Roland played at the larger venue, I went to see him, and the crowd was horrible. Instead of listening to the music, the audience spent the whole night trying to talk over it. At the end of the evening, Rahsaan Roland Kirk told the audience that they were the worst group he had ever played in front of and that he would never come to Atlanta again. “If you ever want to see me again, you will have to come to the Village Vanguard in New York,” were his parting words to the spectators, who by this time had enough sense to shut up.

I went up to him afterwards to apologize for the crowd’s behavior and he told me, “Little girl (he always called me that), you better get out of Atlanta.” I told him, “Yes sir, I will.” Two weeks later I moved back to Athens, beginning one of the most intense periods of my life. The B-52’s had flown the coop but Pylon was on the rise, as were R.E.M., Love Tractor, The Side Effects, and a whole host of other bands. We had some experiences during that time that can only be told one-on-one, and only then to the most discreet of friends.

Keith Bennett

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both):

I was involved in the music scene in both Athens and Atlanta.

2. Your connection the the scene:

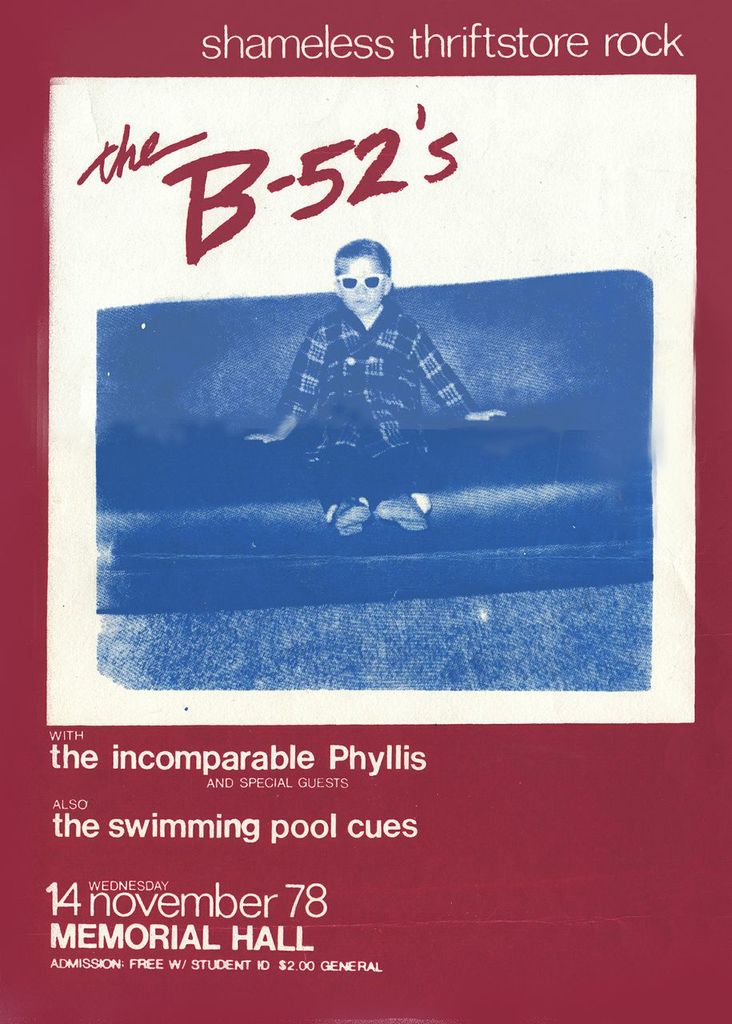

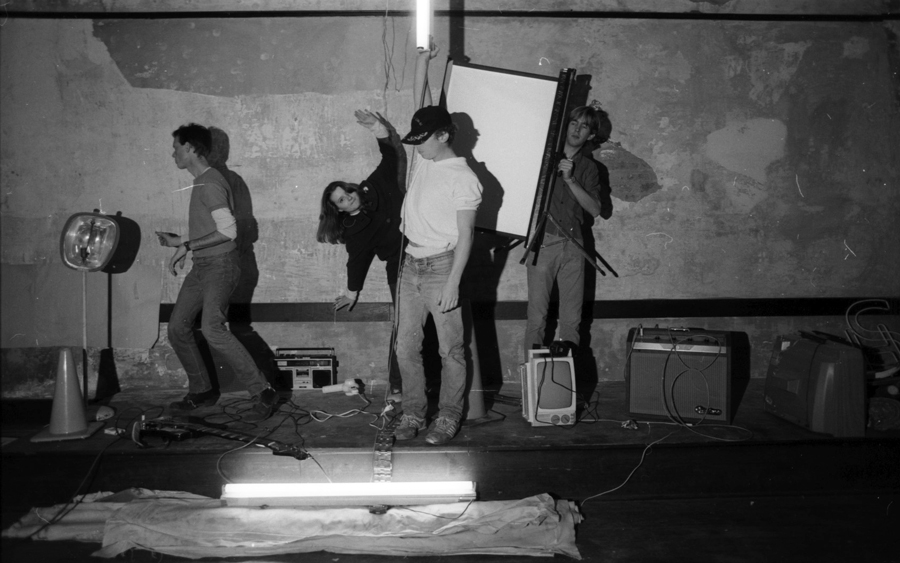

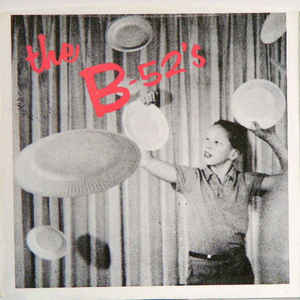

The B-52’s, The Fans, Pylon, The Tone Tones, REM. I was mostly a fan of the bands but I did create graphics for the B-52’s including posters for the group’s performances at the Georgia Theatre in Athens and CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City in New York City. I also designed (with Keith and Ricky’s guidance) their independent single on DB Records, “Rock Lobster/52 Girls.”

In the execution of these projects I designed a logo for the B-52‘s as well. The aforementioned show posters and logo were also part of my exit exam to graduate from UGA with a Graphic Design degree but the work was undervalued by my professors. I received an F for the project and wasn’t allowed to graduate. (I returned the following fall quarter and created an illustration montage in pencil which is what they wanted, not of the B’s but of the Beatles and was able to graduate from college and start work immediately washing dishes at Friends restaurant in the Georgian Hotel, Athens.)

I also accompanied the group on some trips to NYC and helped out here and there. Later, when they signed with Warner Brothers, I became their first roadie along with Moe Slotin, who actually had much experience in rock and roll touring. Since I basically lied to secure the gig, Moe ended up having to train me and he did an excellent job. It was the modern-day equivalent of running off to join the circus, an apt metaphor in more ways than one. Although ultimately it was not my life’s calling, I did end up working three U.S. tours, one Australian tour, and two European tours. I also worked for the B’s in Japan.

At first I did the back line, the keyboards, and set out Fred’s toys and Cindy’s bongos along with being responsible for restringing and tuning every one of Ricky Wilson’s guitars, every show night which was about five to six nights a week, for eight weeks during that first tour. Ricky was a unique guitarist to say the least and played guitars strung with four and five strings instead of the standard six and he had a different tuning for each guitar. On some, I had to change the tunings during the show as he finished with a guitar that he would be using later in the set, which needed another tuning. I was responsible also for going to Manny’s Music in New York, or sometimes finding a music store on the road and replenishing the crates of super heavy gauge strings that he used on his somewhat funky old Mosrites. He also had a lovely Epiphone solid body (stolen years later at the beginning of “Cosmic Thing” comeback) and a Sears Silvertone copy of a Dan Electro complete with amp and speaker built into the case. (They actually used the case amp on stage in the early days, setting it up and putting a mic from the PA in front of it just as a normal amp). Later, he did have some Fender Strats and some yellow chunky off brand guitar he got somewhere.

Moe set up the drums and ran the sound from the house. We were a pretty tight two-man crew and had it down to every square inch in the truck utilized to its best potential. Moe was anal as hell but had also been around so he was a creature of the rock and roll environment. He told me from day one “there’s no down time in rock and roll,” meaning that after the stage is set and guitars strung and tuned and awaiting the group for sound check or after sound check, there was always something to do and no time to just wander off or not be working. There was always some gear to be checked, case to be struck and stowed, a cable to be taped down … on and on. And he was right.

We would pack the rental truck and repack it at first, looking for the perfect pack regarding the cases and their sizes and shapes, but also the order in which they needed to come off the truck for the set up. We got to a point where we could breakdown and load out in record time and we had to because usually we had to drive an overnighter to the next city, check into a motel for three or four hours of sleep, maybe, and then get up and head to the venue, always arriving an hour earlier than the itinerary indicated. And do the whole thing: the load in, the setup, the restringing of guitars, the sound check, the non-down-time period before show time, eating crappy bar food in the beer and cigarette smoke ambiance of the venue while the band went out on their eternal search for vegetarian fare, the show, the break down and load out and we were off again, usually with Moe driving at first and me writing post cards to folks back in Athens and Macon. Sometimes I was so tired I would try to sleep under the furniture in the dressing room until Moe would find me. But it was great. The best job I ever had. And although I had volunteered to work for free, Ricky saw how hard I was working and told the band that I should be paid. I was already getting a per diem, so I thought I was getting paid.

We played clubs mostly, the odd college but also opened for the Talking Heads at bigger venues as the B’s and Talking Heads shared the same management. Standouts from those early days include — Club 57 in New York, The Exit Inn in Nashville, The Agora Ballroom in Atlanta, The Iguana in Austin, U.C. Berkley with the Talking Heads in the middle of the day in front of student union (we parked the Ryder trucks back to back with a stage in between and used them as dressing rooms), The Greek Theater in LA, opening for the Talking Heads, and some crappy Chinese Restaurant by day that transformed into a rock club at night with a load in from hell, up two flights of stairs.

As far as Pylon goes, I knew most of them from art school or just Athens parties.

I never worked for them but saw them perform around Athens before we left town in fall of 79. I did go out to Nicky Generis’ place in the country one time where I played keyboards and Curtis Crowe played drums while Dana Downs sang and Nicky banged out power chords on the guitar. Dana was a little over served and ended up lying on the floor to sing and I was not that experienced in being in a band so I was not catching on to whatever Nicky wanted us to be doing. He would stop every few minutes and scream at the top of his lungs, “No, No, No! That’s not fucking right! It goes duna duna duna dum bam boom,” or whatever and we’d try again and he’d stop and yell some more. The more he yelled, the wider the grin on Curtis’s face and the more incoherent Dana became and I kept thinking, “This sucks. I don’t want to be in a band.” Later, that nucleus grew into the Tone Tones. I played piano but I was not really the performing type, that is to say I didn’t have confidence. The only other times I played with folks in Athens were jamming with the B’s in their Hull Street rehearsal space, just once (awesome!), and dropping by to visit Vic Varney and ending up jamming in his basement with him and some other cats. That’s it.

In the meantime, my good friend Margaret Katz had been going to check out a band called the Fans. We knew the keyboardist, Mike Green, from our dorm days at UGA. The first time I saw them at Rose’s Cantina in Atlanta, I was blown away. To actually know somebody who could write songs like that and make that kind of sound live? I was hooked. I would spend many days and some nights at their house on Seminole, either before or after one of their shows or when in town to catch other acts that came through. Those punk and new wave acts often knew their counterparts in other cities. It was a network, and people would come to the band house to either say “hey” or to crash. We first met Chris and Tina from the Talking Heads at that house, out on the front porch after The Talking Heads and Elvis Costello show at the Roxy in Buckhead. Some of Costello’s band showed up later, jammed with some of the Fans and ended up spitting at each other and nearly fist fighting for some reason. I guess it was punk.

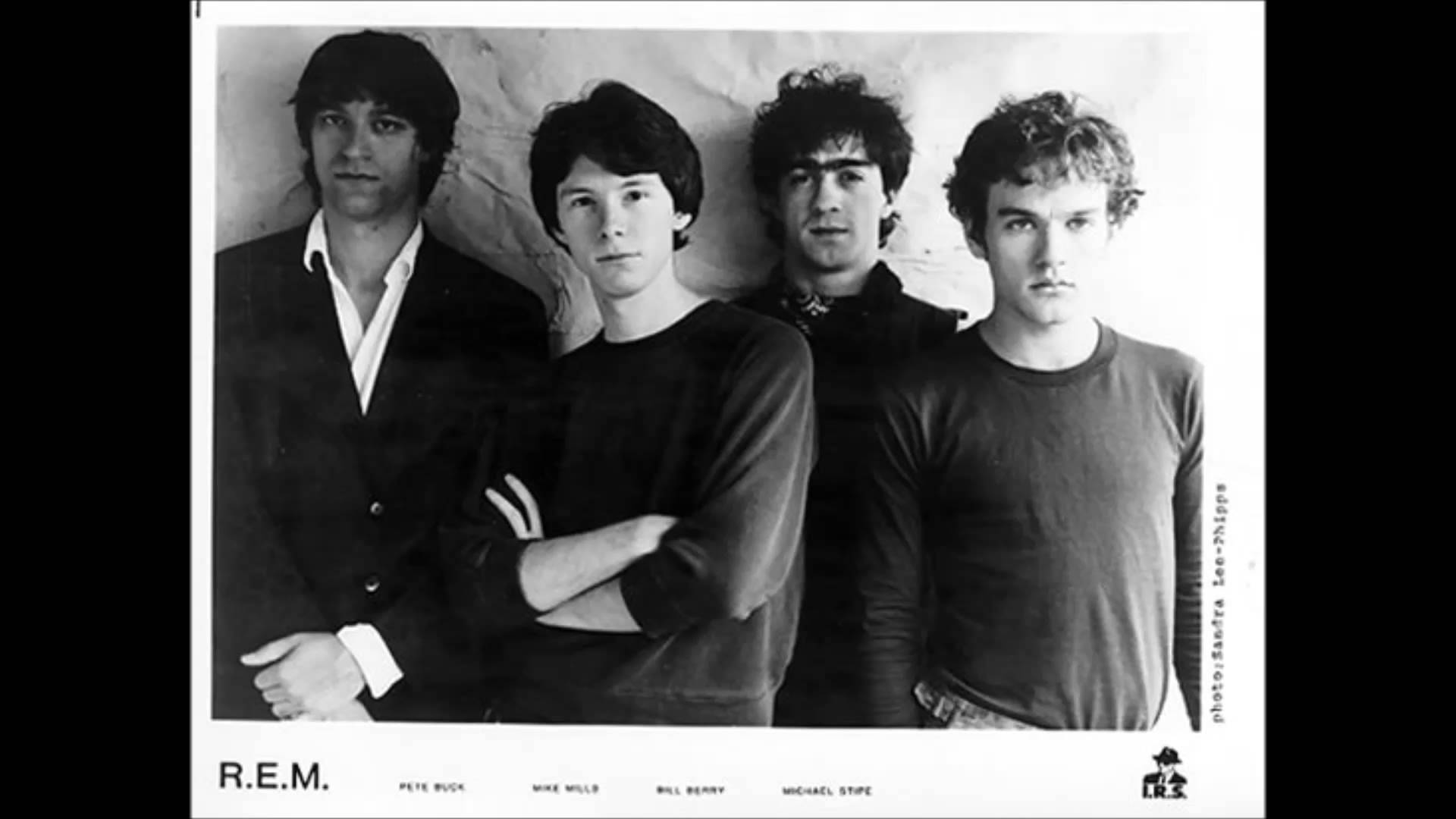

After we had moved away to New York City, we still came home often to Georgia and to Athens. One time while visiting I went to the Caledonia Lounge to catch REM I had heard so much about. I thought, “Man, these guys suck.” Truly, they weren’t up to the standards of other acts coming out of Athens and Atlanta back then. Then, about six months later, I saw them again and they were great. Shortly after that, they began their journey toward world domination. I got to know Bill Berry and Mike Mills pretty well. Both are from my home town of Macon and both were pretty down to earth, talking about the Atlanta Braves and such. I got to know Peter Buck some but not as well and Michael Stipe was a mystery for years, seemingly aloof. However, in recent years I have gotten to know him and like him a lot. But they started after we left town.

Once while visiting, we threw a party in the space that is now the Caledonia but was destined to be the 40 Watt Club for a while. Jimmy Ellison’s band played and Cindy Wilson, Paul Scales and others played a few tunes with them and then a band named Love Tractor made their debut. It was a big night.

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

I saw the B-52’s the first time they performed publicly, at the party on Milledge Avenue, Athens, Feb. 14, 1977. The following weekend, I caught them again at their second party performance in Athens at the residence of Teresa Randolph. I helped them roll up their rug and pack up their minimal gear in an effort to meet Cindy Wilson. Shortly after that, we began dating. Eventually, they signed their major label deal and were going to head out on the road and relocate to New York City (their manager said you couldn’t be in a nationally known band and be based in Athens, GA). In order for us to remain together, Cindy talked the manager into letting me be the one crew member that the hired sound guy would be allowed to have. I volunteered to do this for free even, to sweeten the proposition. The manager said “Sure, cheap labor, keeping one of the singers happy, two for one motel room, you’re hired.”

Moe, however, was not happy about that situation, the singer’s boyfriend going to be on his crew. He called me up in Athens and tried to talk me out of it. He said I didn’t know what I was getting myself into (he was right) and that it would be the hardest thing I’d ever done (right again). He just couldn’t have somebody with no experience trying to do this when it would only be a two-man crew. I did the only thing I could do at that juncture. I lied. It was for his benefit as much as anything because there was no way that Cindy and I were going to be denied this opportunity, especially since it was already a done deal. I thought that I may as well make the cat feel better about it. I told him I’d played in bands in high school (true) and that I had changed strings on guitars (once in a blue moon if one broke, but it was a pain in the ass which was why I started playing keyboards instead – but that part I left out) and that I had set up drums (blatant lie) and after a while, he softened up.

The beginning of the Athens Atlanta music scene represented a life-changing series of events for me and the very thing that was starting to happen unfortunately was the thing that took us far away. Fortunately, the people we knew and still know from those times are so special to us and I feel that no matter where those folks might be, collectively we are all still Athens. It’s more than a place but a shared experience and aesthetic.

4. What are you doing in music now?

Well, I am an art director/graphic designer so I did not remain in the music field after my early roadie years, aside from an unofficial and unpaid position as guest list facilitator. I worked for years in advertising in NYC and Atlanta and designed and produced LP covers on a freelance basis for bands that included the Landsharks, Dreams so Real, Michelle Malone and Drag the River and years later designed a Go Gos re-release of their first LP with additional booklet and bonus material. Also created graphic design for Cindy’s solo project, the Cindy Wilson Band, including press kits, posters, t-shirts and web site. I also designed the B-52’s LP covers for “Mesopotamia” and “Bouncing off the Satellites.”

These days, Cindy and I are still married, so I do kid duty while she goes out of town to do shows. Our kids are in bands, and have been since age 9. Their current act is called ARRAY. India and Nolan, our two kids, play bass and keyboards and sing and write songs in the group and they are rounded out by a few other teen aged kids who are all excellent musicians: Mary Frances Kitchens, who has played with Nolan and India since Mary Frances and Nolan were nine years old, plays guitar and writes tightly crafted songs, Max Leech is their phenomenal self-taught drummer, and the latest addition is Andrew Weisburg on keyboards. I am their manager, crew chief, publicist, booking agent, graphic designer and driver of the car. The only thing I don’t help with is their songwriting. I stay out of the creative.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

Wow, that’s a tough one. Mainly because I’ve told so much that I don’t know of anything left untold. And if there was, it would be for good reason and unlikely I’d tell it here.

Darryl Rhoades

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both, if applicable):

My first band, Darryl Rhoades & The Hahavishnu Orchestra (1975-78) was assembled in Atlanta but worked all over the country selling out venues in N.Y.C., Philadelphia, Austin and beyond. One of my favorite shows was a sold out show in a large concert hall at UGA where Capricorn Records came to see us and passed because we were too weird.

2. Name of your band(s) and your position in the band(s):

My first band was Darryl Rhoades & The Hahavishnu Orchestra (1975-78) and the next band was Darryl Rhoades & The Men From Glad (1985-88). I was the leader, frontman and songwriter.

I have been a drummer/songwriter/frontman since 1967 where I played all the Atlanta clubs with “The Celestial Voluptuous Banana”

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

Playing UGA, Between The Hedges (a small nightclub in the student activities building, Memorial Hall) and the 40 Watt Club always felt like home. WUGA played a lot of my material anytime I came out with a new recording

4. What are you doing in music now?

Currently, I am doing one man shows (comedy), writing an autobiography and working on my 13th CD. I’m also involved with four other songwriters and about to go into the studio to start working on a group recording.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

In 1977, I was invited to perform on the WTBS show “James Brown Future Shock” with my band, The Hahavishnu Orchestra. We were known as a theatrical satirical group that featured dancers, backup singers in drag and usually numbered at least ten members on stage at any given time.

Our set on Mr. Brown’s show was shot during the day with everyone wearing pimp clothes and I made my entrance busting through a perforated record drawn on a large sheet of butcher paper where I met two dancers that were tricked out in street ho threads. The band was vamping when I grabbed the mic and started singing our underground hit, “Suicide,” which was a dance song about how to kill yourself. James was watching us and later I was told by one of the camera men that James Brown was baffled and didn’t understand these crazy white people singing about killin’ yourself to a dance step. He reportedly turned to the camera guy and said “Issat some kinda of joke or sumphin?” I stuck around to see him do the intro and laughed as he struggled to say the band name. He eventually got it close enough when he said “Darryl Roe and the Hahavishnu”. It aired on Dec. 31, 1977.

Video: Here is the you tube link of that performance:

Regrettably, James Brown’s intro and outro to our appearance was not put on the video copy they furnished me.

Kevin Dunn

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both, if applicable):

Inasmuch as my Atlanta band of the epoch — v. (2.) infra. — contained one Athenian, whose presence in the lineup resulted in a substantial number of the art department’s student luminaries and their circle attaching themselves to, nay, creating the group’s sociostylistic ambit, that contact in turn initiating a circulation of reciprocal influence that I flatter myself persists to this day, I’m gonna say both.

2. Name of your band(s) and your position in the band(s):

The band was the Fans. I was the guitarist and second-string Komponist, sang mostly backup except on my own tunes. The other personnel were: Alfredo Villar, principal songwriter, lead singer and bassist; Russ King, drummer; and Mike Green, the above-cited Athenian, keyboards.

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

(1.) supra. When, in 1975, my very old friend Harry DeMille began the association with DB Recs founder Danny Beard, whose links to Athens were legion, that would lead to (among other things of well-documented moment) the creation of the music emporium Wax ‘n Facts in Atlanta’s Little Five Points district, the Fans were in desperate need of a simpatico keyboardist. Danny recommended Mike, he being possessed of considerable avant-garde cred, as a plausible candidate. The recommendation panned out, Mike joined the band, and the bi-urban connection was forged in train. The band was holed up on Seminole Avenue in Inman Park, in what was then a desuetude two-story yellow-brick house from the neighborhood’s heyday in the 1920s (it’s quite nice now), and the art party raged on within the ramshackle hulk’s walls pretty much nonstop for three years or so.

4. What are you doing in music now?

Playing stringed and fretted things, either solo (lots of ambient loops, and Middle-Baroque repertory on original instruments) or in the context in divers aggregations, for no money, same as it ever was, as the poet would have it. I released a solo album in 2012, The Miraculous Miracle of the Imperial Empire (kevindunn.bandcamp.com). Having within the last twelve months decamped from the ATL to the Classic City to get married, I am with my new bride Heli, my intermittently-resident son Malcolm, and assorted other players investigating various configurations of material and approaches thereto.

Being both garrulous and repetitive, I doubt any such anecdote, at least as qualified, exists. I’ll instead share with you a top-of-mind bit of rue: it is a permanent source of professional regret to me that I was, during the sessions for the B-52s’ DB Recs single, unable in my capacity as what I like to call “production sherpa” to persuade the band either to deploy an envelope follower-ring modulator combo on a doubled track of the descending guitar figure on “Rock Lobster” or to retain the original Farfisa bass track with the lacuna effected by that one blown analog oscillator on “52 Girls.” Pity, really. If they’d just taken my advice, I’m sure their career would have fared so much better. LOLLOLLOLLOLLOLLOLLOLLOL

And that’s all I got. Mwah.

Robert Croker, The Fans, and the Drongz

One of the most influential teachers in the University of Georgia Department of Art was Robert Croker. His art education began at age 15 at the High Museum of Art. Before coming to UGA, he received an MFA from the University of Arizona in 1966. In his words, “Lamar Dodd rescued me from oblivion” at LaGrange College when Dodd recruited Croker to teach drawing and painting at UGA.

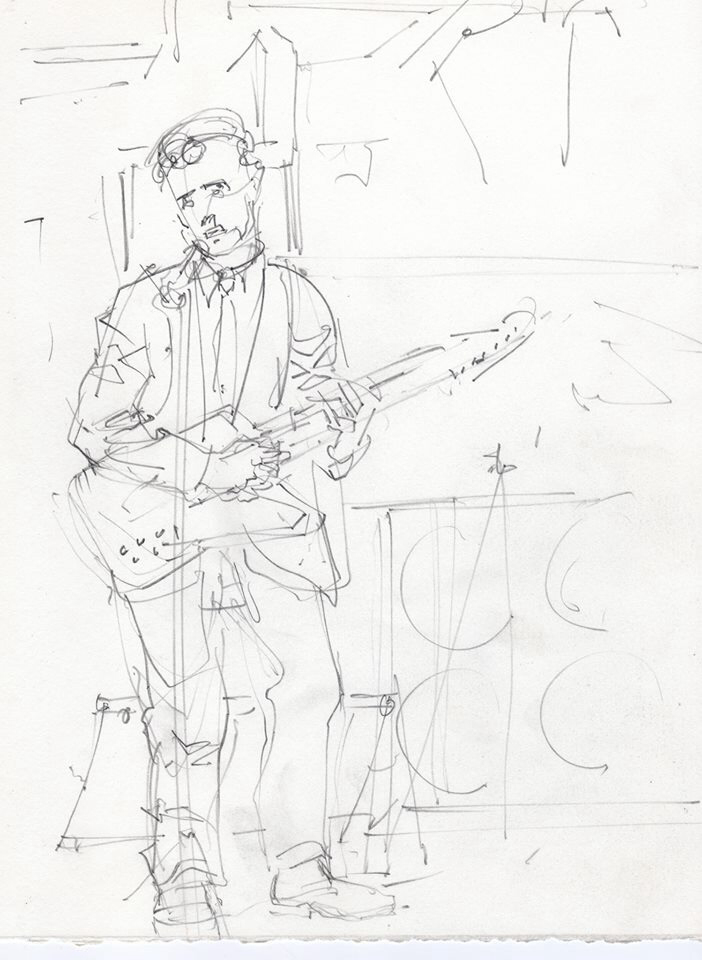

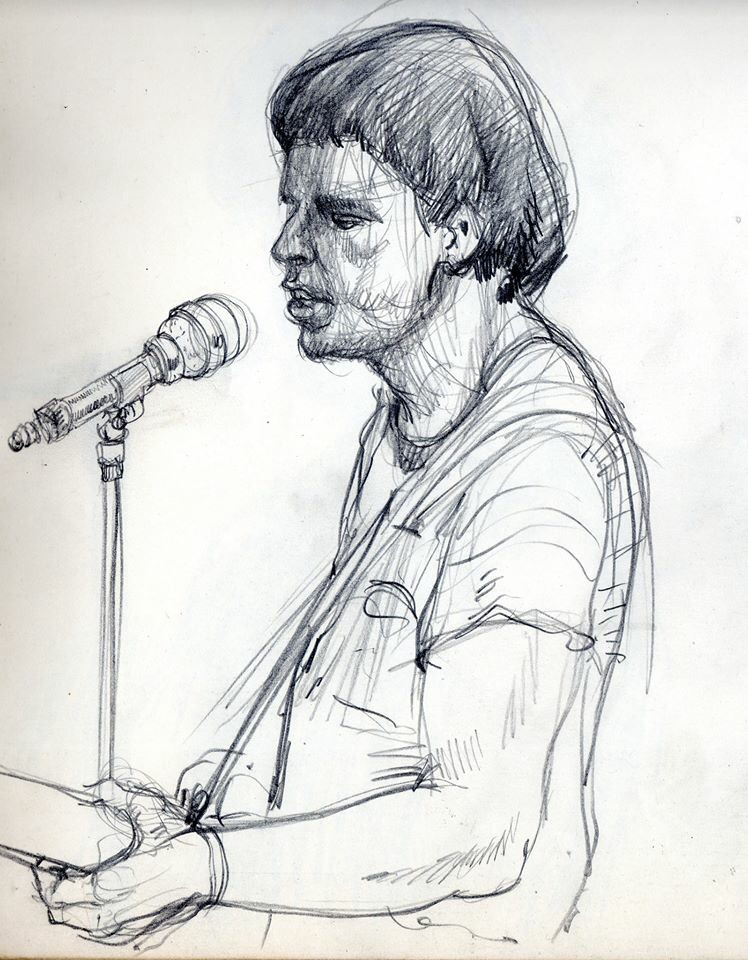

Sketch from Notebook

Medium: Graphite on paper

Credit: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift of the artist in memory of Margaret Katz Nodine.

During his tenure on the UGA campus, Croker taught Introductory Drawing for seven years. He became a major influence on his students (Including Pylon bassist Michael Lachowski) through his innovative teaching techniques, and in his last year at UGA, his independent study classes and individual critiques sometimes lasted late into the night.

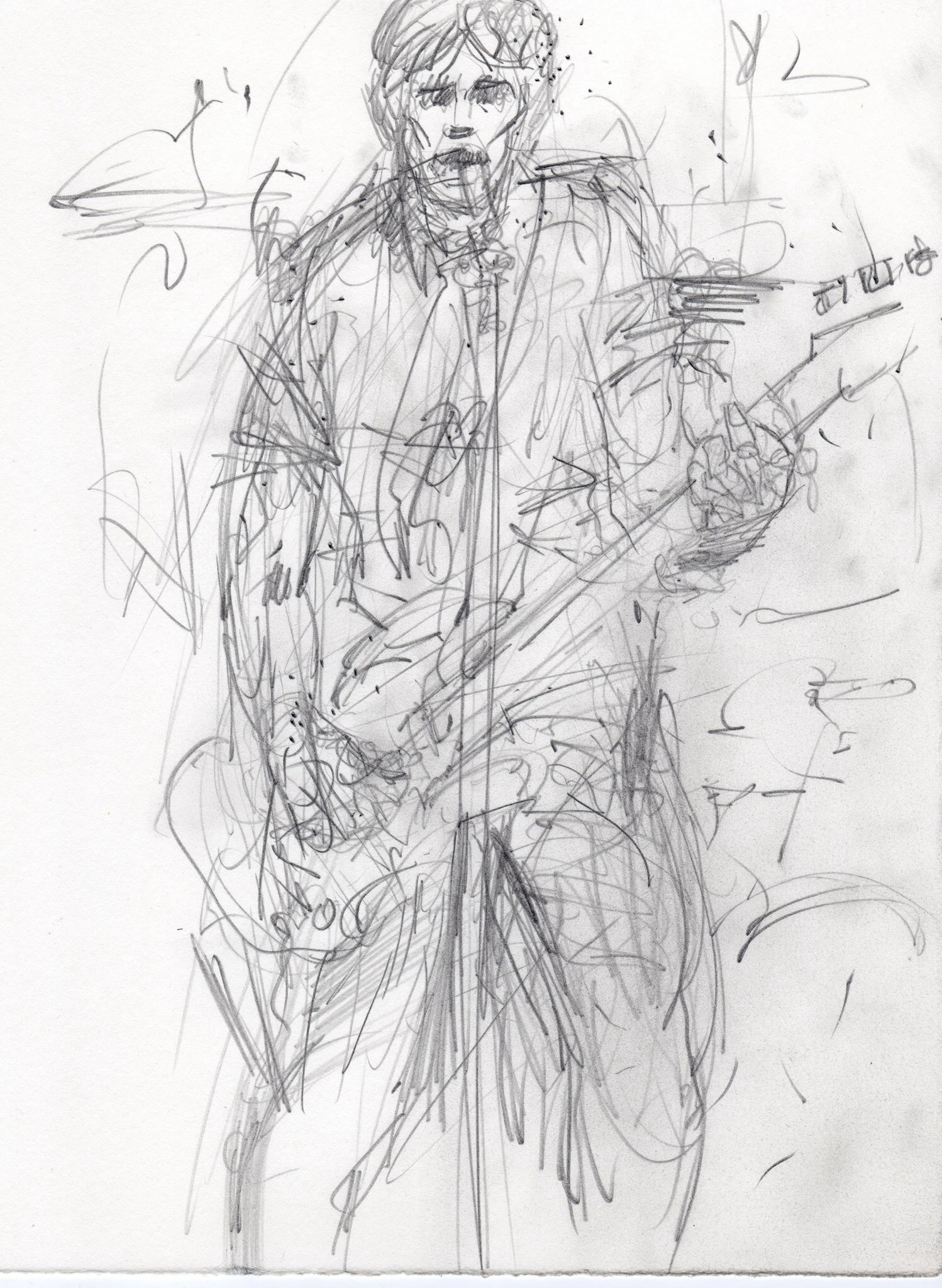

Sketch from Notebook

Medium: Graphite on paper

Credit: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift of the artist in memory of Margaret Katz Nodine.

Total immersion in art was the rule, and the art building was open 24 hours a day to accommodate the prodigious amount of work that was being produced.

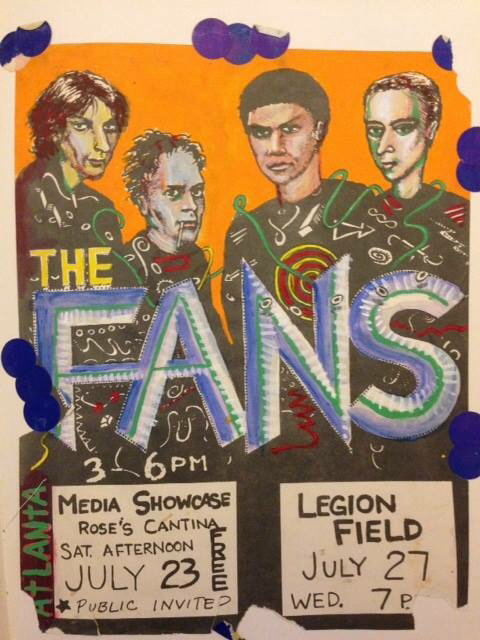

Sketch from Notebook

Medium: Graphite on paper

Credit: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift of the artist in memory of Margaret Katz Nodine.

Part of the discipline – if it could be called that – was that students were encouraged to make drawings (drongz) everywhere they went: — restaurants, bars, and night clubs were favorite places to make some of the 100 drawings that each student was expected to come up with each week.

Sketch from Notebook

Medium: Graphite on paper

Credit: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift of the artist in memory of Margaret Katz Nodine.

Croker drew everywhere he went as well. The drawings seen here are from two of his sketchbooks, which he donated to the Georgia Museum of Art in memory of Margaret Katz-Nodine, one of his most talented students. Along with being a gifted artist, Katz, as she was known in those days, was also a “living, breathing part of the [Fans],” according to Croker.

Sketch from Notebook

Medium: Graphite on paper

Credit: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift of the artist in memory of Margaret Katz Nodine.

This particular set of “drongz”, as Croker calls them, came from The Fans performing at Rose’s Cantina in Atlanta, and CBGB’s in New York City.

Doreen Cochran

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both):

Atlanta

2. Your connection to the music scene:

The Brains, band coordinator

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

When the Brains played with the B 52’s first time. You were there!

4. What are you doing in music now?

Nothing in music now.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

I told my friends about this and they said, “What story haven’t you told?” Well, really the story I haven’t told is that I am not as knowledgeable in the music biz as everyone thought. I just knew I liked the Brains and I could organize and sell them. I was flattered and just didn’t let on…..

An addendum to Doreen’s answers from Maureen:

Doreen was one of the central figures in the Atlanta music scene, in part because she managed the Brains and ran the Brains’ fan club, which was one of the best organized fan clubs going at the time. She was also important because she was a woman doing a job that most women were not given an opportunity to do. I managed the B-52’s and she managed the Brains, so we always presented a united front. Her claim that she didn’t know what she was doing doesn’t hold water with me, except for one thing. We were all walking through uncharted territory. The only thing we had that set us apart from the rest of the bumbling idiots was that we had each other. Athens bands and Atlanta bands supported each other and shared information to a degree that would be unthinkable today.

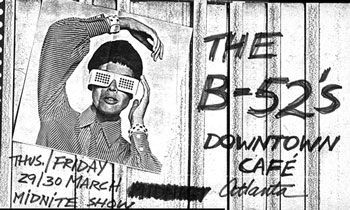

The show with the B’s that Doreen refers to here was at the Downtown Cafe in Atlanta. I remember taking a walk with Tom Gray after sound check, and he told me, “Maureen, I have written a song.” His words were full of wonder, and I knew that whatever this new song was, it must be something really special. That night, the Brain’s played Tom’s new song: “Money Changes Everything.” It was the song that catapulted Tom and his band into the fame stratosphere when Cyndi Lauper recorded it three years later.

Video: Tom Gray performing “Money Changes Everything” with another epic Atlanta band, the Swimming Pool Q’s, January 28, 2007.

Glenn Phillips

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both, if applicable)

Throughout my 50 years as a musician, I’ve been based in Atlanta and played Athens countless times as well.

2. Name of your band(s) and your position in the band(s)

I was a founding member of the Hampton Grease Band in 1967, as well as one of the band’s two principal songwriters (myself and Harold Kelling). When that group broke up in 1973, I started playing and recording under my own name and now have eighteen albums out, including two with Jeff Calder (of the Swimming Pool Q’s), under the name Supreme Court. I’ve also recorded with Cindy Wilson of the B-52s, Pete Buck of REM, Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead and many others.

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

The Grease Band was based out of Atlanta and started playing Athens in the late ’60s. That continued for me throughout the ’70s and ’80s, and Cindy Wilson and I did a show together at last year’s AthFest. I’ve always thought of the two cities as being creatively connected, and I feel incredibly lucky to have ties to both.

4. What are you doing in music now?

My first solo album “Lost at Sea” was recently rereleased as a 40th anniversary double-vinyl album on UK label Shagrat Records (it was originally released on Virgin Records), and this fall they’re putting out a live album of my 1977 show at London’s Rainbow Theatre. I’m also in the midst of recording my next album of new material and still playing out live.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

I’ve never told the whole story of how and why the Grease Band started the free concerts in Piedmont Park in the spring of ’68. Although we’re known today for the eccentric music on our double album “Music to Eat,” when we first started out in ’67, we thought of ourselves as a blues band. This was right before the blues explosion hit the South, although at the time, soul music was quite popular here, like Motown and James Brown.

We considered ourselves blues purists, though, and would never play anything as commercial as James Brown, so when we played one of our first jobs at a high school dance, the reception was not enthusiastic — we cleared out the room. We figured the high school crowd just wasn’t hip enough for us, although it may have also had something to do with the fact that we stunk: We were just starting out and most of us could barely play our instruments.

In any case, we decided to take our music where we thought we’d be appreciated, to an African-American club called the Poison Apple Room. Atlanta was still a pretty segregated city back then, but the owner hired us anyway. He was hoping to expand his business by drawing some white kids to his club and saw us as a possible way to do that. I think he also felt sorry for us — we were like dogs at the pound looking for a home, and he took us in.

Once we started playing for the club’s audience, though, our dreams of acceptance collided with reality. Unfortunately, they knew the difference between the real thing and a group of oblivious suburban white teenagers. Nonetheless, they politely tolerated us, although one member of the audience decided to give us a music lesson. He walked up to the bandstand while we were in the middle of a song, reached into his coat, pulled out a gun, and pointed it at us. Then he made a request, “You play some James Brown or I’m gonna blow your fuckin’ head off.”

As I mentioned earlier, we’d never played a James Brown song in our lives, but it’s amazing how fast you can learn to do something when there’s a gun pointed at you. We launched into the worst ever cover version of “Popcorn,” and from that point on, the club’s owner would greet us each night at the door with, “You boys need to sell those goddamn guitars and amplifiers, and buy you some p**sy.”

The reception we’d gotten at the high school dance and The Poison Apple Room got me thinking we might want to find some other places to play. I had noticed there was an electrical outlet in the Piedmont Park pavilion, and in the spring of ’68, I took a clock radio down there and discovered it was a live outlet. The following weekend, the band set our equipment up on the grass, plugged in, played and crowds of hippies started gathering around us. We asked no one for permission nor did we apply for any permits — prior to our makeshift concerts, no electric bands had played there before, so this was uncharted territory, but we kept it up every weekend, and by the middle of that summer, the shows had grown to include many other great Atlanta bands. By the following summer of ’69, we were doing shows there with the Allman Brothers and The Grateful Dead.

Great things have strange beginnings.

Video: This clip features Cindy Wilson of the B-52s with Glenn’s band doing “Give Me Back My Man,” which seems perfect given the subject of the Atlanta and Athens music connection:

The featured image of the B-52’s at the top of this story was photographed by Terry Allen and is used with the kind permission of the photographer.

Join the conversation and share your favorite memories of the Athens and Atlanta music scene in the comments section below!

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.

Robert L. Croker

January 28, 2022 @ 2:41 am

I’m proud and happy to see some of my drongz on this site, BUT… The poster for The Fans (Legion Field and Rose’s Cantina) above is credited to me, but the artist is Robert Nielsen, an extraordinary talent, wit, and born anarchist, who had a finger in every slice of every pie in Athens, and who would occasionally show up for classes, if only to disrupt them. He currently lives on Long Island, where he and his wife Billie produce “Billiebeads” custom jewelry. He is also still crazy as a Junebug…

William R. Barnett

April 14, 2018 @ 1:58 am

Not sure of the name of the nightclub (?) at UGA’s Memorial Hall, but there was a Between The Hedges music club and it was under world famous Allen’s Bar on Prince Ave in Athens where I definitely saw Darryl Rhoades there in ’73 or ’74.Helped me with my music education immensely. LOL!

Curtis Knapp

August 16, 2016 @ 4:11 pm

If the Piedmont Park B52s photo of everyone is an SX70, it is my photo. I took and gave away a bunch that day in Atlanta. Wonderful day!

John Harriman

July 24, 2016 @ 9:25 am

I had the honor of recording and playing cello on Glenn’s “Lost at Sea” album. And in between 1975 – late 1990`s Glenn had me play on a few songs in some other of his albums. However the biggest thrill was to come back after 40 years with the majority of the original band members to relearn the songs and perform the 40th Anniversary “Lost at Sea” Album show to a sellout crowd in Duluth, GA.