‘I’m an activist who became an artist’: Remembering Harry Belafonte, 1927-2023

His sense of humor surprised me. You don’t expect living legends and civil rights icons to be funny. But yes, Harry Belafonte had jokes. Memories of my 2016 conversation with the activist, actor and singer came flooding back Tuesday morning as my phone screen filled with news alerts reporting Harry Belafonte’s death at age 96.

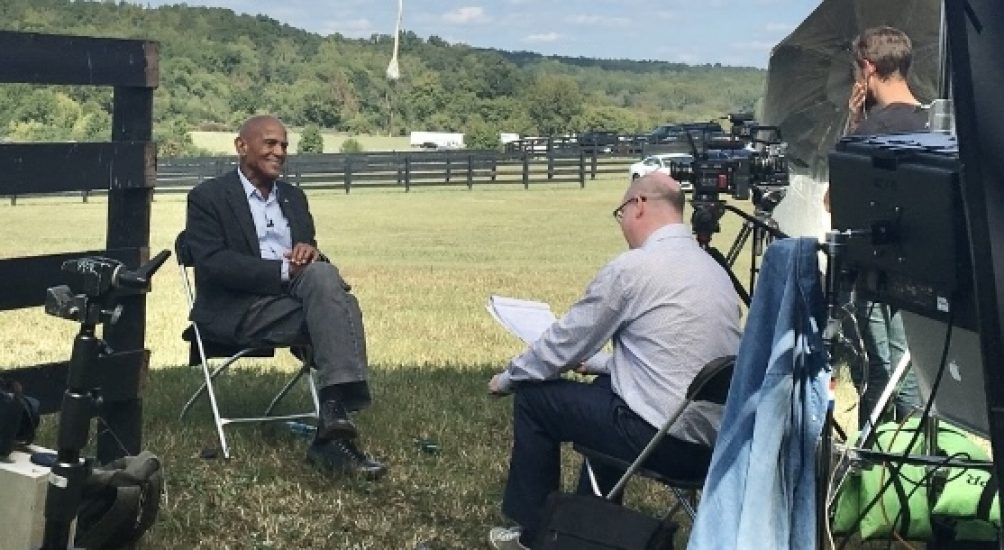

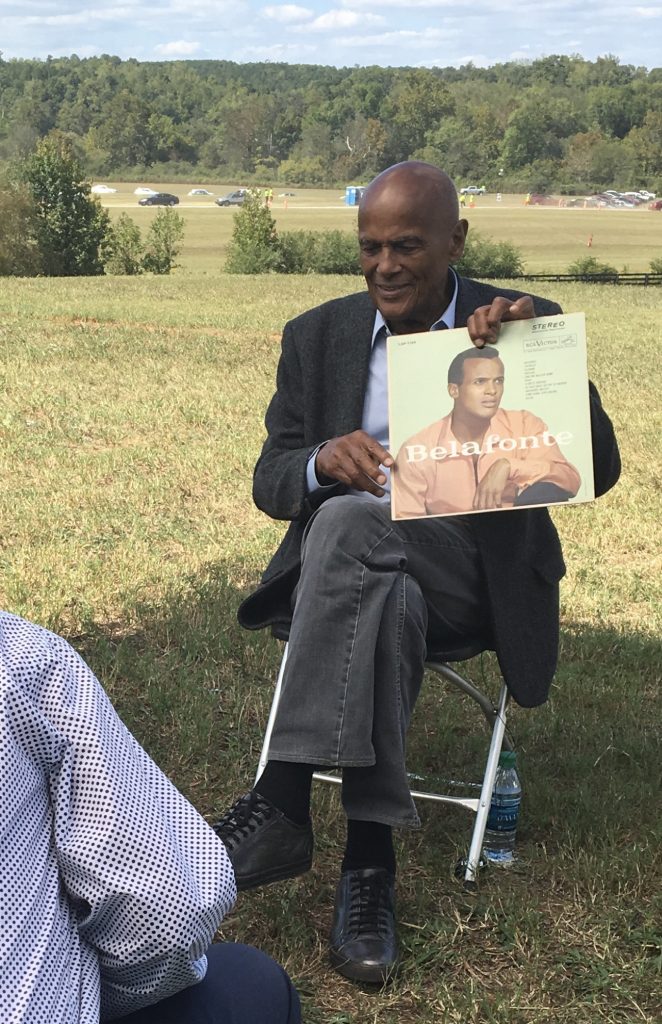

Back in October, 2016, thanks to my friend and then-Billboard magazine deputy editor Isabel Gonzalez-Whitaker, I was sitting in a field in remote Fairburn, Georgia overlooking the two-day Many Rivers to Cross festival. The veteran civil rights fundraiser had asked the likes of John Legend, Common, Macklemore, Santana and Dave Matthews to perform for 22,000 attendees and to donate their time to the cause.

The weekend was a benefit for Belafonte and co-director Raoul Roach’s social justice nonprofit, Sankofa. My interview was set to run as part of Billboard’s annual “Music + Philanthropy” issue. Having raised millions of dollars over the decades for civil rights and social justice causes, Belafonte was a natural fit for the issue.

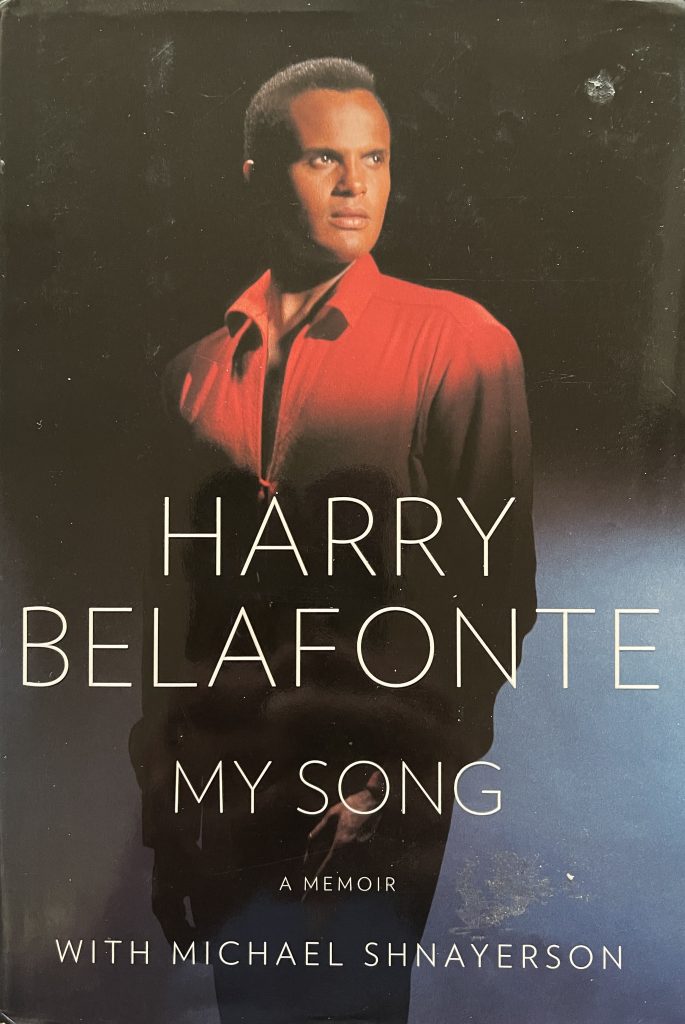

Me? I was decidedly a less natural fit for this assignment. I was a print journalist suddenly surrounded by videographers, photographers and an audio-video team who had literally set up a makeshift film set in the middle of a field to shoot our conversation for Billboard. I had spent the last 24 hours poring through Belafonte’s memoir, “My Song,” along with all three volumes of Taylor Branch’s civil rights trilogy and Nelson Mandela, Coretta Scott King, John Lewis, Xernona Clayton and Andrew Young’s memoirs to research the questions for my 30-minute interview.

As I waited for the video crew to do a light test, I nervously flipped through my pages of questions. Suddenly, an unmistakable voice leaned over and said, “Can I tell you something? You’re the most important man in this vicinity.” He waited a beat, smiled and added, “Make me look good.” I laughed, relaxed and then gently reminded Mr. Belafonte that all the lights, cameras and microphones were trained on him.

Below us on the stage, Public Enemy blasted through a spirited rendition of “Fight The Power” as they finished their set in front of a fist-pumping crowd. A crowd — and an artist roster — organized by Belafonte himself, the same as he had done 51 years before in Alabama when he assembled Johnny Mathis, Tony Bennett, Nina Simone, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter, Paul and Mary and Joan Baez to perform on an outdoor stage constructed of caskets from the local African-American funeral home to entertain and to energize the crowd marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965.

I’ve been asking famous folks questions for over three decades but Harry Belafonte was the first individual who spoke in uninterrupted paragraphs, neatly punctuated. And when he had finished answering a question, he sat in silence and awaited the next question. He didn’t stammer, he never searched for a word. His great intellect and wisdom percolated through every response. If his busy schedule would have allowed, I’d have sat there in that field all afternoon, listening to him recount his life and his philosophies regarding the betterment of mankind.

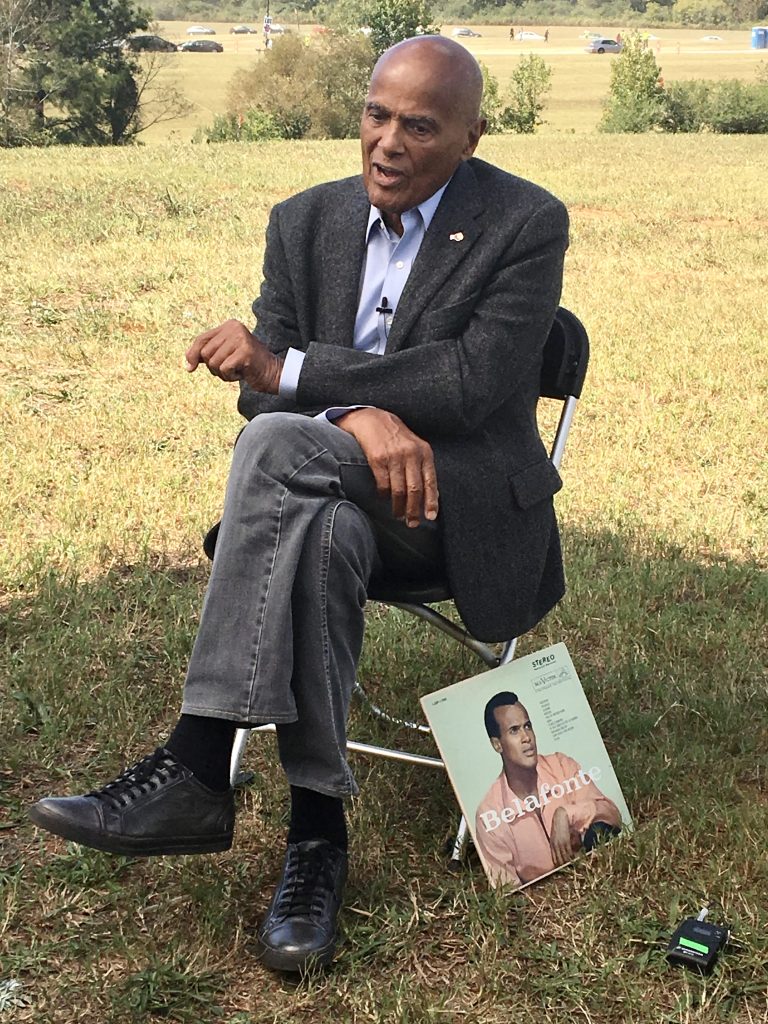

Oh, and the answer is yes. In the fall of 2016, exactly five months before his 90th birthday, Harry Belafonte remained one of the most strikingly beautiful human beings to ever frame an album cover or a movie screen.

But as is the case with most interviews, for the purposes of Billboard’s tightly focused “Music + Philanthropy” issue, much of our conversation had to be left on my digital recorder. As a tribute to Harry Belafonte’s life and legacy, Eldredge ATL is pleased to share with readers the rest of Belafonte’s powerful and inspirational interview from that October 1, 2016 afternoon.

Eldredge: As someone who has spent your life organizing events like this, as you were driven onto the site of the Many Rivers to Cross festival this morning, did your memory drift back to Selma in 1965?

Belafonte: When I was called to participate in this rather lengthy historical campaign titled the civil rights movement, it was the state of Georgia where I first came. It was here that Dr. King was born. It was here that he resided and a lot of the work that he did was headquartered in Atlanta. When we decided to revisit that memory and energize some of the work we’re doing for the future, coming here was a poetic concept — let’s go to where it all started. Yes, I think of Selma on days like this and the march from Selma to Montgomery and of coming here with the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] and with Dr. King. A lot of memories are evoked. What most pleases me is that so many people are showing up here this weekend. What is most beneficial from that fact is that the movement is not dead. There is still a heart that is courageously struggling for the rights of our citizens.

Eldredge: Fifty-one years ago in Alabama, you assembled the likes of Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis Jr., Nina Simone and Joan Baez and as we look around us here, you have the same galaxy of today’s talent with the same commitments and the same goals. What’s your secret to mobilizing people like this?

Belafonte: The secret to mobilizing people is really motivated by the fact that people are in need of being mobilized. I would have imagined by now we would have settled the voting question. We got the right for Black citizens to vote through acts of the U.S. Supreme Court that Dr. King targeted. And yet, now here we are, all these many, many years later fighting the same issue. As long as there is a struggle, there is going to be a need for us to mobilize. I think the opposition needs to understand that we do not sleep. We may appear to be asleep but we are not asleep.

Eldredge: You founded Sankofa in 2013 out of a sense of need. When did you recognize that another social justice nonprofit was needed in 21st century America?

Belafonte: When I realized the Black community was in distress and in need of financial resources. One of the best ingredients in our community is our arts community. They attract a lot of attention, they attract a lot of audience. I’ve never known America to have as rich a harvest of celebrities as we do right now, coming out of the music business, coming out of the motion pictures and certainly, the world of sports. I can hardly think of one professional game that doesn’t reflect the large presence of the Black community. When our community is looking for resources to help fund things, we turn to our artists to make the commitment because they can pull the audience and they can pull the currency. So when I called a lot of my arts friends and talked about this moment, they willingly stepped into the space.

The fact that I was paid these vulgar sums of money in order to practice this thing that I had fallen in love with was the motive for saying ‘Let’s direct those resources toward places and events that would help to change human history.’

Harry Belafonte, October 1, 2016

Eldredge: In your estimation, what most needs to be eradicated?

Belafonte: (Pausing for 10 seconds before answering) The thing we most want to eradicate can be identified with one banner. It’s called racism. I do believe the issue of race plagues America deeply. And when we are lulled into believing the issues of race have been settled from one period to the next, we are awakened by a new set of realities that say, ‘Well, it’s not quite settled.’ You still have Black men being shot down by lethal process, by representation of the law. You still have communities that are plagued by the gun. We still have people who are disenfranchised. As long as that environment persists, I think we have to continue to mobilize and let our voices be heard to try and change the way in which the system is working.

Eldredge: Over my career, I’ve had the privilege of talking with Mrs. King, Ambassador Andrew Young, Congressman John Lewis and Xernona Clayton. Congressman Lewis told me, “Whenever there was a need, I would hear Dr. King say, ‘Call Harry.’” In both our conversations and in their memoirs, they all credit you for showing up with the money whenever there was a need. You would show up to the SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] offices or where ever the need was with a bag containing sometimes $60,000 or more in cash. To this day, do you have any idea how much money you raised? Does it go into the millions?

Belafonte: Oh, yes, that’s for certain. And by the time I got my hands out of the pockets of other artists’, it was in the multi-millions! (laughs) We were an important instrument in keeping resources flowing to the cause. When I stepped into the world of show business, I really didn’t have my eyes set on a specific. I wasn’t thinking about how great it would be to be Clark Gable, how great it would be to be Bing Crosby or how great it would be to all of these illustrious images that graced our culture.

What really moved me was when I saw plays by Clifford Odets and Langston Hughes or when I saw stories being told that reflected the human condition. I said, “I want to be in that space. I want to be a storyteller.” I’m an activist who became an artist, not an artist who became an activist. And in that context, I found that there was a lot to sing about, there was a lot to talk about.

The fact that I was then paid these vulgar sums of money in order to practice this thing that I had fallen in love with was the motive for saying let’s direct those resources toward places and events that would help to change human history. It wasn’t the purpose of my mission, but I got to meet people like Eleanor Roosevelt. She was a remarkable woman. When I spoke with her and dined with her and got counseled by her, it really helped to shape my political sense and the world in which I existed. She introduced me to the new leaders of the continent of Africa while she was a representative of the United Nations for the United States government. This was while she was working on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [in 1948]. She did incredible things.

She reached into the crowd to me and said, “Come work with me.” Then, out of that I met [Paul] Robeson, Dr. [W.E.B] Du Bois and Dr. King and John Lewis. I could go on and on — Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker. It was just an endless parade of magnificent human beings that touched my life. With this reward, I got much more than I bargained for. In that context, I’m going to be 90 in a few weeks. I’ve lived almost a century of life and it has been well spent because I kept good company.

Eldredge: When you look back over your long life and your commitment to civil rights and social justice, what are the moments that stand out to you now where you realize times were changing, that things were improving because of your efforts?

Belafonte: The first major display of that force, that life revelation, came with the March on Washington [in 1963]. I had known that our march would be supported but I did not expect over a quarter of a million people to show up. I did not expect so many great people to step onto that platform and say some of the most glorious things since Abe Lincoln’s Gettysburg address. It was a stunning moment. The best speech of the day, including Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech? It was the speech John Lewis gave. That speech was a profound declaration that inspired and moved a lot of people. We are very blessed that the state of Georgia gave us John Lewis.

Eldredge: You’ve spent a lifetime planning, executing and financing nonviolent protests. In your view, what next steps can Black Lives Matter take to keep its mission moving forward?

Belafonte: I genuinely believe the principles set forth by Dr. King’s mission, where he reached into his Gandhian philosophy, when he reached into his relationship to the Christ story. All of these things were attracted into his being and he made utterances that influenced masses of people to the right end.

When I met Nelson Mandela, one of the things that made him reach out to me was the fact that, while in prison he watched our movement very closely. He said he asked himself, “Who is this man Martin Luther King Jr., who are these people striking a blow for democracy?” He modelled what South Africa and the ANC [African National Congress] did upon what the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] and what the American civil rights movement did. By those facts, I understood we were on the right trajectory, on the right path. And I do believe that all of the leaders who are emerging today to pick up the struggle and to perfect its future, have chosen the right path.

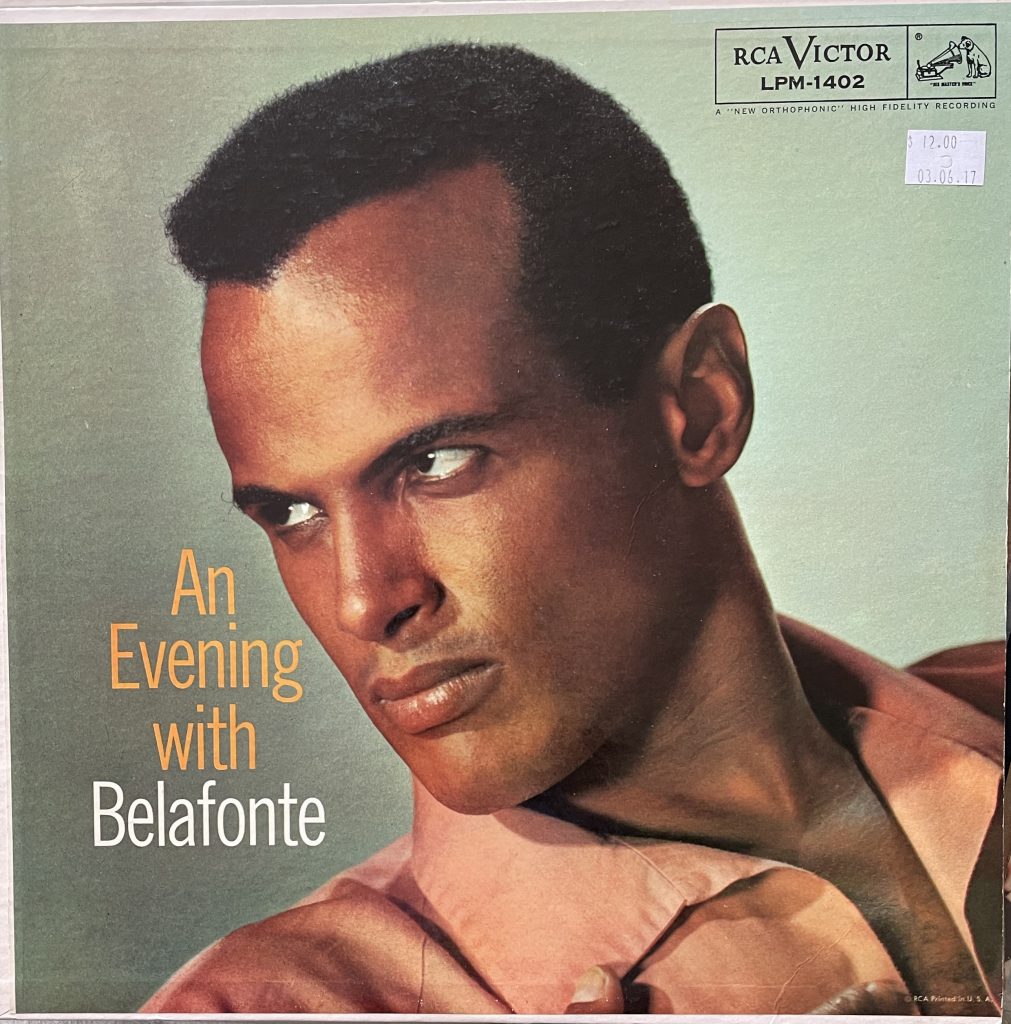

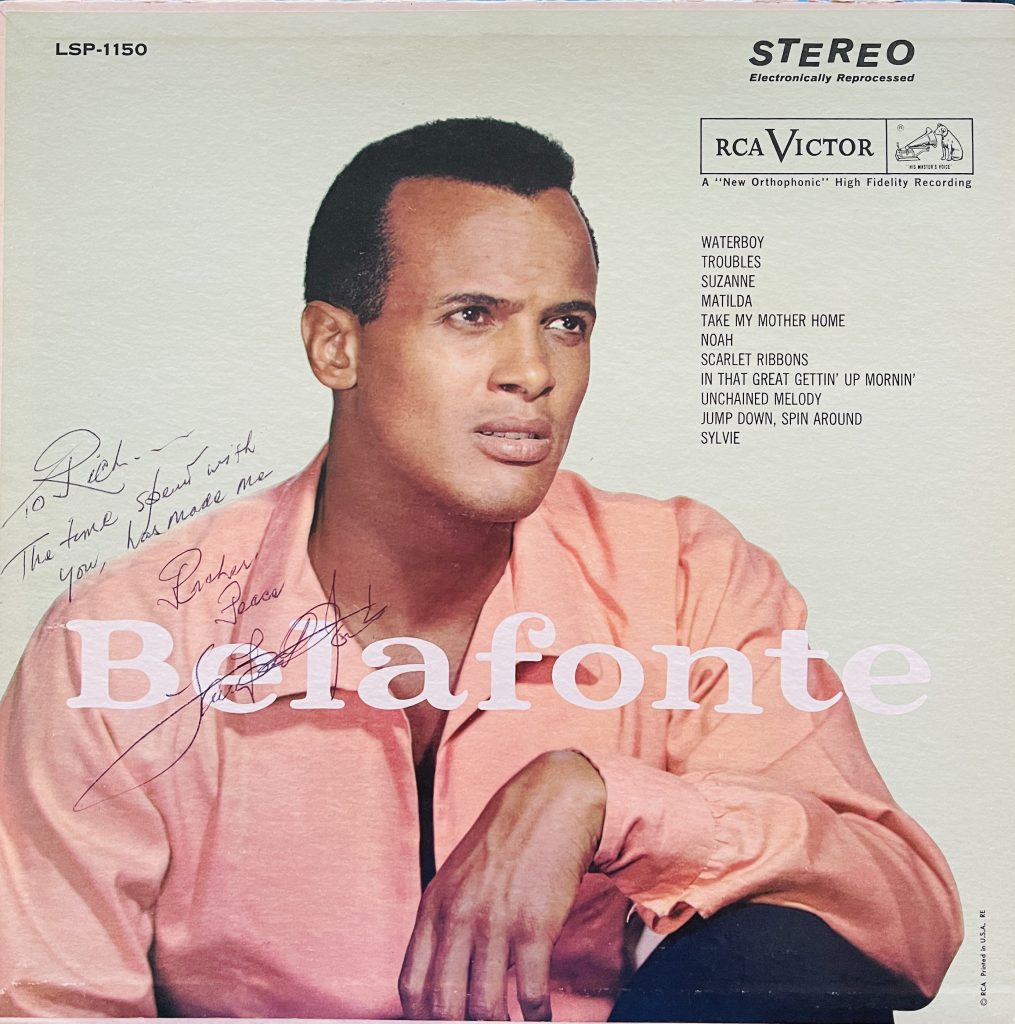

Eldredge: (picking up a copy of his debut album for RCA Records, “Belafonte,” released in 1956 and handing it to him) My last question, Mr. Belafonte, is this: This strapping young man who posed for this album cover in 1956, what would you tell him about the state of America today? What does he need to know?

Belafonte: First, he should know he has a very constipated look. (laughs). The fact that this turned out to be a million seller was indeed a stunning response to me.

I think knowledge about the challenges that face us is a constant necessity. It must never go away. If we do not watch with vigilance, what happens to this fragile thing we call democracy, then, I think we are doomed to fail. The very nature of democracy’s vulnerability is the nature of the ingredients that shape our philosophical concept. When the Greeks came up with the idea, they were onto something that changed the course of civilization. We have got to understand that democracy lets all things be heard. Democracy also picks what will prevail. And if the right side of equation is what governs the human heart, then we’re on the right path. If it doesn’t, then we’ve missed the boat. We can’t afford to do that.

I think there are a lot of things I could have done better. But I would hope that my future influence, my future work would be to encourage other artists to take the leap that I did to help affect change.

Still holding the LP as we wrapped up the interview as the lapel microphone was removed from his shirt and the cameras stopped recording, Belafonte requested a pen. Without a word, he then inscribed the album, “To Rich, The time spent with you has made me Richer. Peace, Harry Belafonte.”

I thanked him for both the autograph and his time. I wanted to say more to him. But out of the corner of my eye, I saw “Rush Hour” actor Chris Tucker standing by himself with a Belafonte album of his own waiting to be signed. I realized the organizer of the Many Rivers to Cross music, art and justice festival had to get back to work.

Ten minutes later, as the video team finished breaking down the makeshift set, these people I had met just three hours before the interview in a barn onsite, came over to me, thanked me for such a strong interview and wrapped their arms around me.

In the span of just a couple of hours, we had bonded.

I was happy but still surprised by the sweet gesture when I spotted Belafonte’s black SUV slowly exiting the area. The back window rolled down. A beaming Belafonte stuck his head through and yelled, “Get your hands off him. He’s mine!”

We all stood laughing when I impulsively decided to dash over to the vehicle. I stuck my hand through the still-open window, shook his hand and said, “Mr. Belafonte, thank you again for such a powerful interview. It was a pleasure to meet you.” Harry Belafonte patted my hand and said, “Young man, the pleasure was all mine.”

A moment later, with gravel dust still hanging in the air, the SUV and Harry Belafonte were out of sight.

Chattahoochee Hills photos of Belafonte and Eldredge taken by Sonia Murray, Oct. 1, 2016.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.