From Civil Rights to Lady Gaga: 25 Years of Talks With Tony Bennett

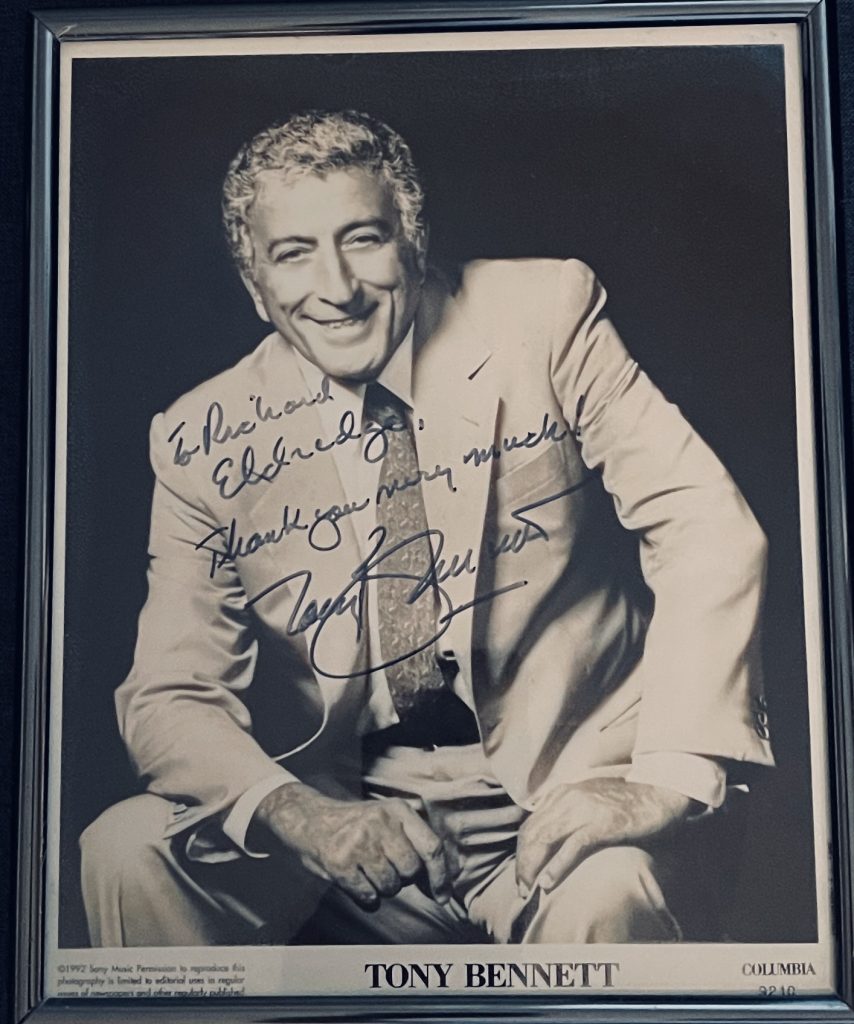

In the middle of an editorial meeting in the Spring of 1990, the conference room phone buzzed. It was Kim, the Atlantic City magazine receptionist. “Rich, Tony Bennett is on line two.” I resisted the urge to roll my eyes as I quickly interrogated the facial expressions of my co-workers. As the magazine’s new, fresh out of J-school associate editor, I was routinely the target of interoffice practical jokes. One floor downstairs, Kim must have sensed my skepticism. She quickly added, “Really, Rich!” I glanced over at the phone. Line two was indeed blinking. Then I remembered the voice mail I had left in the Columbia Records PR Department a few days earlier requesting to speak with the singer about his new album, “Astoria: Portrait of the Artist.”

I dashed into my office, pressed line two and picked up the receiver. “Richard? It’s Tony Bennett. I received a message that you’d like to discuss my new album. I hope you don’t mind my calling you myself.” The voice on the other end was unmistakable.

Thankfully, an advance cassette of his new album had been lodged in my car player for a week and I had already pored through the Fed Ex envelope containing his latest press kit. Cradling the phone between my chin and shoulder, I pull out the album press notes and completely winged my first interview with the legendary performer.

It was the first of what would become a series of conversations we would have over the course of my now 30-year career. While I’ve interviewed hundreds of famous people through the years, Mr. Bennett has a special place in my heart. He’s the only performer I’ve interviewed in every decade of my career, from the days I got carded anytime I walked onto a casino floor during my two years at Atlantic City magazine, fresh out of college. And then, through my 16 years at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and my current role as a contributing editor at Atlanta magazine.

When famous folks die, my phone doesn’t usually blow up. But when word spread Friday morning of Mr. Bennett’s passing at his home in New York at age 96, four dear friends immediately texted to express their condolences. That’s what the singer’s life and music meant to us. Throughout our nearly 25 years of conversations, the performer was always kind, accommodating, a complete professional and very punctual. On Friday, I spent the day going back through our interviews together. Listening to Tony talk about his unparalleled career, served as the perfect balm as tributes to him poured in from across the globe. Here’s a selection of Mr. Bennett’s wit and wisdom, dispensed to me over two and a half decades of reporting on his career.

Atlantic City, 1990

As I was embarking on a career back in 1990, Tony Bennett was hitting the reset button on his. After 15 years away from Columbia, the label that had signed him in 1952, (and the same label that let him get away in the early 1970s when he famously battled against recording contemporary rock material), he was back and now, as part of his new contract, was finally cutting the kinds of albums he always wanted. As he once told me, “Columbia was always focused on the next hit single. I wanted to create a hit catalog.”

“Astoria: Portrait of the Artist,” an autobiographical song cycle named for his old Queens neighborhood, was a stepping stone on that comeback path. When I asked what inspired him to re-cut one of his first big hits, “Boulevard of Broken Dreams,” he told me, “Unfortunately, the song remains relevant in 1990. It’s obscene to see a country like ours with such a high rate of homelessness. We have to find a way to address the problem and give these people their dignity back.”

Bennett’s soothing jovial voice inspired me to be a bit more confident, so I allowed my inner jazz nerd out to ask the singer about recording with likes of Count Basie, Stan Getz and Bill Evans. “All of those albums were recorded with great care. I refuse to compromise and I won’t put out a record unless I feel it’s a good performance.”

As a former college intern at Spin magazine, I asked Bennett what inspired his recent feature-length interview in the youth-skewing rock monthly. “I was thrilled with the Spin thing,” he said. “I’ve never been a believer in that whole ‘generation gap’ concept, anyway. Young people today are very open to things and have a very keen interest in the older standards. Actually, most of the time I feel like a 15-year-old myself!”

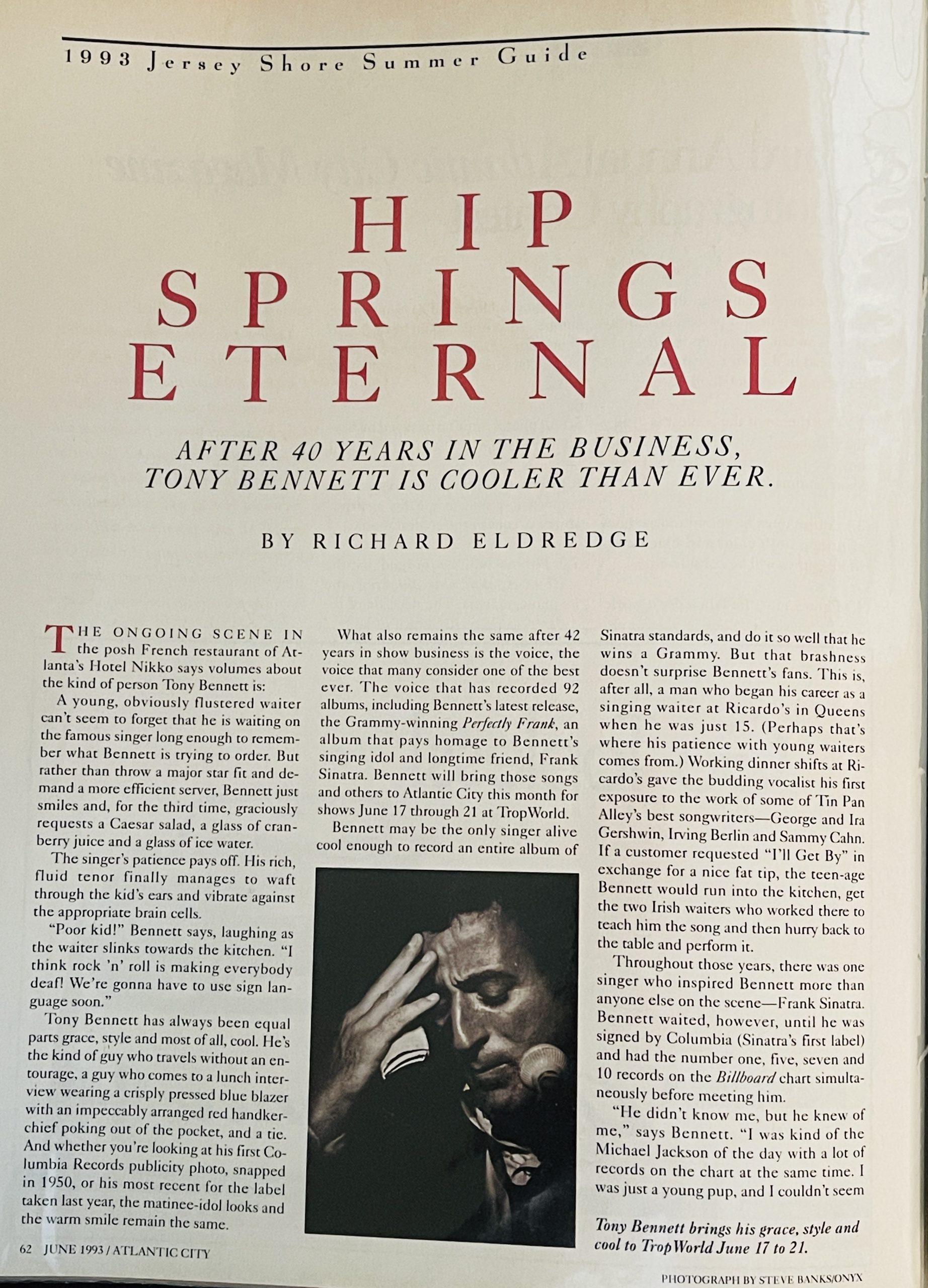

Hotel Nikko, 1993

Three years later, in Atlanta, we met up for lunch to discuss “Perfectly Frank,” his Grammy-winning jazz trio tribute to pal Frank Sinatra’s saloon and torch songs, recorded with longtime pianist and arranger Ralph Sharon.

Again, sans entourage, the singer glided off an elevator by himself and into the lobby of Hotel Nikko at noon sharp, wearing a crisply ironed blue blazer with a crimson pocket square poking out. He greeted members of his trio checking in while simultaneously guiding his guest toward the doors of the French restaurant.

At lunch, the singer’s tastes were simple — a Caesar salad with grilled chicken and a glass of cranberry juice. But the young server waiting on Bennett couldn’t seem to forget that he is waiting on the famous singer long enough to remember his order. Bennett kindly repeated his order. On the third try, the singer’s rich Astoria, Queens-accented voice finally registered and the server slinked off to the kitchen. “Poor kid!” Bennett said laughing. “I think rock n roll is making everybody deaf. We’re gonna have to use sign language soon!”

Bennett’s patience with the young server perhaps came from having started out as one himself at Ricardo’s in Queens at 15 in 1941 as a singing waiter. If he didn’t know a requested tune, he’d run into the kitchen and ask the waiters to teach it to him. Then, he would dash back to the table to perform it in exchange for a fat tip. Among the most requested songs? Sinatra’s hits with his then-big band boss Tommy Dorsey.

Twenty four years later in an interview with Life magazine, Sinatra famously said, “For my money, Tony Bennett is the best singer in the business.”

When I read the quote back to him, Bennett gracefully side-stepped the compliment. “Sinatra pulled me aside one night backstage at the Paramount Theatre and gave me this piece of advice: ‘Don’t ever compromise. A lot of producers are going to try and have you do some quick novelty song that will make quick bucks. Only sing a song if you like it. Otherwise, you’re going to hate singing it night after night. Only go for quality.'”

As the waiter returned to clear away the salad bowls, Bennett, the visual artist, could no longer resist the table’s view of the Japanese garden outside. He pulled a small sketch book and a pencil out of his jacket pocket and set to work using small delicate strokes. Slowly, the rocks and trees outside began to emerge on his pad.

“Painting is a great joy for me,” he told me. “I paint every day the same way I run scales every day. I think you have to be disciplined in life. I like to bring watercolors with me when I’m on the road. Believe it or not, I learn a lot about singing through painting.”

Having taken up an hour of his time, I clicked off my recorder and closed my notebook to indicate I’d gotten everything I needed for my magazine feature on his creative rebirth.

Bennett glanced at his watch and said, “I don’t have to be at the Fox Theatre for sound check for another two hours. Would you stay and have coffee with me?”

For the next 30 minutes, the singer regaled me — off the record — with stories about his friends Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Rosemary Clooney, his encounters with songwriters Ira Gershwin and Harold Arlen and his old battles with Columbia Records to make the kinds of records he wanted instead of covers of Beatles tunes.

“Now, all they want are concept records!” he said laughing. “I can record whatever I want. What I regret about the music business today is only Sinatra, Bruce Springsteen and I have that freedom. When I was coming up, a performer’s individualism was the most important thing. Dinah Washington, Peggy Lee, Kay Starr, Jo Stafford, Sinatra, Mel Torme, Rosemary Clooney and Doris Day could all sing the same song and sound completely different. They each had their own style. Now, these young kids get built up by these record companies only to find out their career lasts three weeks. It’s obscene.”

99X Concert, 1994

In April 1994, on the heels of “Steppin’ Out,” his Grammy-winning tribute album to Fred Astaire and his now-legendary “MTV Unplugged” concert, Bennett was back in Atlanta to perform an exclusive concert for the alternative rock station 99X as part of the station’s Live X series, accompanied by his longtime pianist Ralph Sharon. Performing for kids in Pearl Jam T-shirts standing next to grandmothers at King Plow Arts Center, the singer seduced everyone in the room with his half century catalog, including “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” and “Body and Soul,” while pausing to tell the crowd about his friend Billie Holiday. As Bennett stayed for more than an hour after the performance to pose for photos, I walked up to one of his original fans to ask for a quote. “”The only regret I have about being here,” the 67-year-old whispered conspiratorially, “is that I didn’t bring any underwear to throw on the stage.”

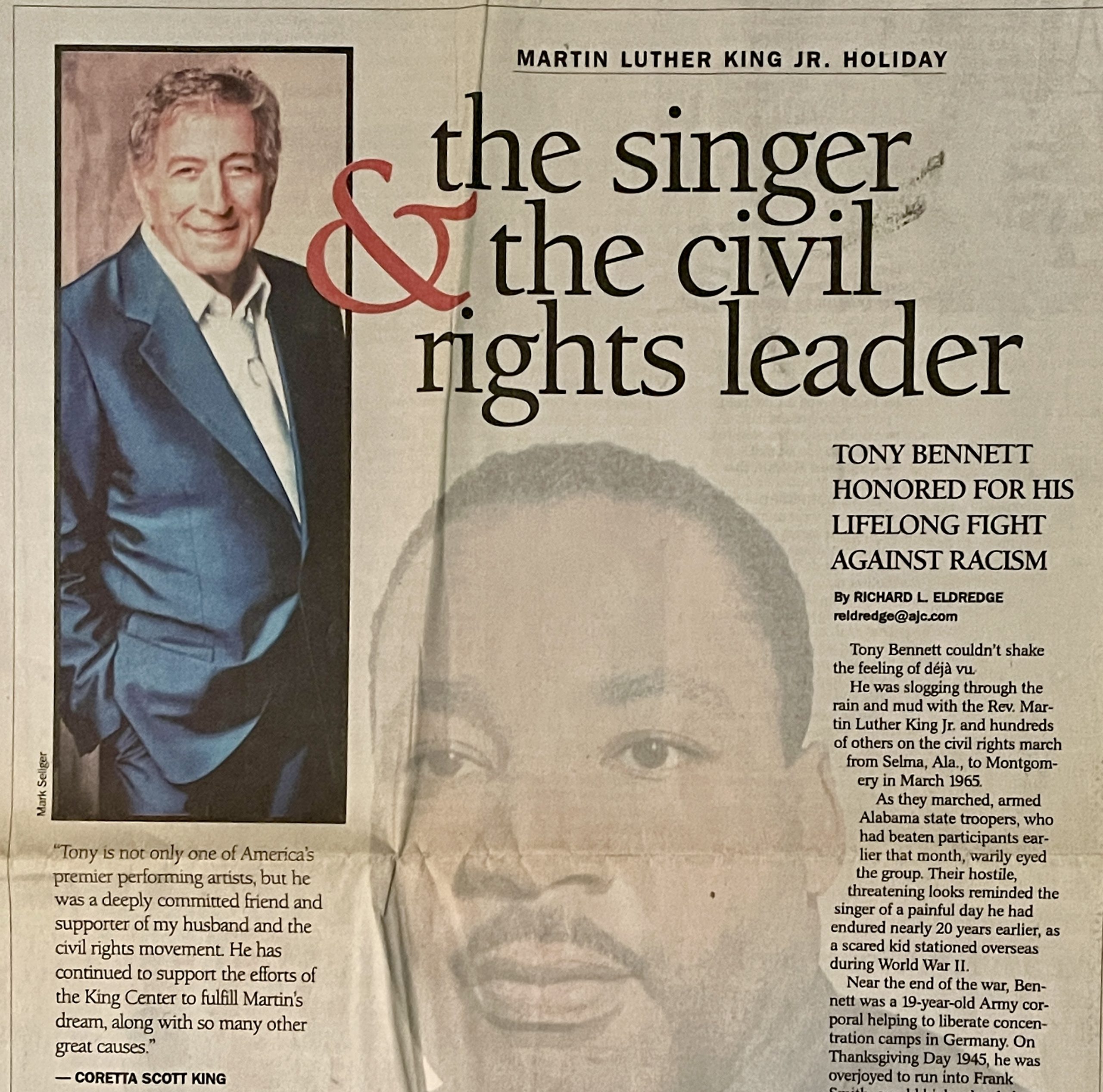

King Center, 2001

Just before Christmas in 2001, I was writing the AJC’s daily Peach Buzz column when I received word that Coretta Scott King would honor Tony Bennett at the annual King Center Salute to Greatness fundraiser. I immediately wrote up the item for the next day’s edition. When I got to my desk the next morning, an email from an irate reader was waiting: “Did the King Center run out of qualified Black people to honor?” While I was initially taken aback, the email inspired my proudest conversation with the singer.

It became clear that although Bennett had detailed it in his 1998 memoir, “The Good Life,” many people had no idea about his work behind the scenes in the civil rights movement. When his friend Harry Belafonte called him in 1965 to ask for his help with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee planned march from Selma to Montgomery, the lifelong social and political progressive immediately said yes.

I emailed Bennett’s longtime spokeswoman Sylvia Weiner and pitched her an idea about a story on Bennett detailing his contributions to the movement pegged to the Salute to Greatness dinner in January. A week later, the singer was once again on the other end of my phone.

Our conversation on that morning was the most personal and painful I ever conducted with Tony Bennett. He described the sense of déjà vu he felt as he trudged through the mud with Dr. King and the hundreds of marchers in Alabama in 1965 as armed state troopers glared at them.

Bennett told me the scene reminded him of Thanksgiving 1945, when, as a 19-year-old corporal, he was overjoyed to run into Frank Smith, an old high school pal from New York. The pair reunited while liberating concentration camps in Germany. Bennett invited Smith to have a holiday meal in the Army dining hall. Upon entering the hall, Bennett recalled, “A superior office took a razor, cut the stripes off my uniform, threw them on the floor and spit on them. He told me, ‘You’re no longer a corporal, you’re a private. Get your stuff. You’re outta here.” Bennett’s old high school buddy was a Black man. The future singer was then assigned to digging up mass graves of American war casualties and reburying them in individual plots.

“I just could not believe that such bigotry existed in the United States Army,” Bennett told me quietly. “It was deeply humiliating for both of us. It was just incomprehensible to me that I was being condemned just for being buddies with Frank. To this day, we can barely speak to each other about that day. It’s just too emotional.”

Years later in 1958, Bennett had just wrapped the recording of his trailblazing jazz record “The Beat of My Heart,” created with the top jazz drummers of the day: Chico Hamilton, Jo Jones, Billy Exiner and Art Blakey. For the album cover, in recognition of their work, Bennett proudly posed with the drummers, most of whom were Black. Days after “The Beat of My Heart” hit record shops, Columbia Records yanked it.

“They had meetings about the cover, and they were worried about how it would sell in the South, so they replaced it with a text-only cover,” he explained. (When “The Beat of My Heart” was reissued by the label on CD in 1997, Bennett, now in his role as Columbia’s elder-statesman recording artist, made certain the original cover was used).

So in 1965 when his pal Belafonte phoned about the march in Alabama, “I jumped right on it,” the singer said. “When we all got there, though, there was some apprehension. We were one step away from being in a war again. I remember thinking, ‘This is uptight — watch it.’ I couldn’t believe the people down there were used to all of that.”

In the evenings, Bennett told me he and the other celebrities on the march, including Sammy Davis Jr. and Billy Eckstine, performed for the marchers. “One night we found this clearing in a field, but there was no stage. Someone knew a mortician, who loaned us 18 caskets, and we made a stage out of them.” After the march, Bennett was driven to the airport by Viola Liuzzo. Later that day, the 39-year-old civil rights activist was shot and killed by Ku Klux Klansmen.

Dr. King expressed his appreciation to Bennett in a typewritten letter dated April 5, 1965, a letter that proudly hung in Bennett’s Manhattan office for decades. “I speak for myself and for the courageous 300 marchers and all the other people spurred on to those final miles to the capital in Montgomery,” King wrote. ”Your talent and goodwill were not only heard by those thousands of ears, but were felt in those thousands of hearts, and I give my deepest thanks and appreciation to you.” Below the salutation, King added in his handwriting, “The SCLC could not make it without friends like you and neither could I.”

Before hanging up, Bennett reflected on a recent conversation he’d had with Harry Belafonte on the tumultuous time. “Harry just reaffirmed for me that we’re all political animals when injustice is happening,” he said. “We’re all such a small speck in the face of the universe. Every single person on this planet is important and should be respected equally. As Billy Eckstine told me that day in Selma, ‘Hey, if this country doesn’t work, the world isn’t going to work.'”

Fox Theatre, 2011

Now as an Atlanta magazine contributor in advance of his November 25, 2011 concert at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre, Mr. Bennett and I kicked off an interview by discussing his tradition of turning off all amplification at the historic 1929 theatre and bouncing his voice off the venue’s back wall. He had learned the trick decades earlier, playing the chain of Fox Theatres across the country. “I played the one in Atlanta, there was one in the Midwest, there’s one in San Francisco. They’re beautiful. They’re like the Radio City Music Hall. They’re a lot larger than a lot of the other theaters and acoustically they’re perfect. That’s where I like to work. I don’t like the big stadiums. I always look forward to coming back to the Fox in Atlanta and having them cut the microphone. Anytime I can do that, I love to do it. There aren’t a lot of those places left. You’ve got to take advantage of those perfect acoustics whenever you have the chance.”

For his new “Duets II” album, Bennett had just cut his first duet with fellow New Yorker Lady Gaga. On paper, the pairing sounded crazy. On record, it was sublime. “I just love her completely,” he told me, sounding like a smitten teenager. “We hit it off instantly. I’ve been doing this for a long time. I’m 85 and I first became well known in 1950. I was the Justin Bieber of my time. But I’ve never met anyone who performs better than Lady Gaga. She sings beautifully. She plays terrific piano. She knows how to dance. She reinvents herself day to day. I’ve never seen anyone as intuitive and as creative as Lady Gaga.”

Tragically, Bennett’s pairing on the project with Amy Winehouse on the Billie Holiday chestnut “Body and Soul” turned out to the last thing she recorded prior to her 2011 death of alcohol poisoning at age 27. As delicately as possible, I asked the singer about the similarities between Winehouse and his friend Lady Day, both taken from the world too soon by substance abuse.

Bennett paused for a moment to collect his thoughts. He told me softly, “It was wonderful to work with Amy but tragic at the same time.” Anger rising in his voice, he added, “I wanted to get a hold of her and her father and sit them down together. I wanted to tell her, ‘You’ve got to stop or you’re going to die.’ This young angel of a great singer who sang better than any of the young singers out there is gone.”

He allowed his anger to dissipate and told me, “I wish you could have heard Billie Holiday when she wasn’t on drugs. You would have been amazed at how good she was. She was so much better when she wasn’t high. It’s the same thing with Amy Winehouse. If only she had stopped. Everybody loved her. Everybody cared for her. It’s a tragedy.”

To lighten the mood, I shifted our conversation to the Johnny Mercer tune “I Wanna Be Around,” that became a standard in his act after serving as the title track on his hit 1963 album. I asked him if it was fun singing a song so out of character with his public persona. “It’s funny, I’ve never looked at it as a mean song,” Bennett chuckled. “I think it’s something that happens to everybody on the planet. At one point or another, we’ve all been in that guy’s shoes [laughs]. Somebody’s going to break your heart. I look at it as a lesson in how to forgive when you’re tempted to be that mean.”

I closed our conversation that afternoon by tiptoeing my way into inquiring about Bennett’s infamous 1971 album, “Tony Sings the Great Hits of Today,” featuring a drawing of Bennett in psychedelic hipster threads on the cover. The album served as a breaking point for Bennett and Columbia Records. He loathed the album and wrote disparagingly of it in his memoir. I had unearthed a pristine original pressing of the album in the dollar bin at Criminal Records a few weeks before our interview and was amazed at how it had mellowed with age. In the intervening decades, the tunes on the album, written by Jimmy Webb, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the Beatles and Steve Wonder, had all ended up becoming modern standards. I asked the singer if he had ever re-evaluated it.

“I have,” he told me. “It’s funny you mention that. It’s going to be included in a big boxed set [Tony Bennett: The Complete Collection] that Sony is putting out of seventy-five of my albums from 1950 to now. I’ve been listening to the digital versions of them. My catalog is still enjoyable for me to listen to because we used the best orchestras, the best musicians. The albums still hold up. Turns out, even that one!”

Chastain Park, 2013

My final interview with Tony Bennett in the Spring of 2013 might also be my favorite. I once again let my inner jazz nerd out as I had in our first interview in Atlantic City in 1990. The occasion was the release of the singer’s long-lost live recording, “Bennett/Brubeck: The White House Sessions, 1962” recorded with the Dave Brubeck Quartet at the base of the Washington Monument. Brubeck and Bennett, both at the top of their game, had been invited by President John F. Kennedy to perform for journalism students spending the summer in the nation’s capital. Listening back to our conversation a decade later, it’s impossible to detect which of us was more excited to discuss the previously unreleased musical treasure.

An archivist at Columbia Records had unearthed the mislabeled recording following the jazz pianist’s death the previous December at age 91. I could practically hear Bennett beaming through the phone as he excitedly told me, “I can’t believe they’ve resurrected this wonderful concert. I couldn’t believe it when they sent it to me! The remarkable thing for me when I heard it again was that it sounded like I sound today. It just shows that being around great jazz artists like Dave Brubeck, you can learn a lot. It doesn’t sound dated at all. It sounds like something I would be doing today.”

I related to Bennett that he and Brubeck sounded like a couple of jazz tennis players in the finals at Wimbledon. For example, on the opening number together, Bennett throws to Brubeck unexpectedly in mid-phrase by announcing to the audience, “Come along and listen to the lullaby of. . .Dave Brubeck!” Not missing a beat, Brubeck served back the melody to Bennett equally unexpectedly. I told Bennett, “On this recording you can almost make out the two of you smiling and sweating up there, can’t you?”

“Absolutely!” Bennett conceded laughing. “You can even hear me tell the audience at one point, ‘Please give us a break because we’ve had no chance to rehearse this thing. Wish us luck!’ It was just completely spontaneous. I loved it. As a performer, I always listen to the audience. And that day was very special because it was an audience comprised of young people who had just graduated from colleges all over the country invited by the president to the White House. They were journalism students. They were going to be the future reporters and interviewers of the world and their reaction to what we were doing on stage was so wonderful and spontaneous. It was thrilling and it fed into what we were doing up there.”

His comment immediately made me think about that equally green reporter and interviewer Bennett had cold-called in Atlantic City that Spring afternoon in 1990. So as we were wrapping up our interview, I took the opportunity to remind the 86-year-old of his kindness that day and how much our 23 years of conversations had meant to me.

“I could tell back then that you got the music,” Tony Bennett told me. “It’s always a pleasure to talk to someone who gets the music. I hope you’re coming to the Chastain show. I love playing there. It feels like the whole public of Atlanta is out there with you. And they’ve always been beautiful to me. That’s what fuels me. To have a crowd that warm and receptive every single time you play in front of them is just beautiful. I can’t wait to come back and sing for you all again.”

Thankfully, in his 70-year career, Tony Bennett did a lot of singing, leaving behind hundreds of hours of recordings for us. Sleep well, sir.

I am indebted to Atlanta photographer and filmmaker Clay Walker for graciously allowing Eldredge ATL to use his photograph (above) of Bennett performing in 1996 at Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park for this appreciation.

Tony Bennett Suggested Listening

The singer released nearly 100 albums over the course of his 70-year career. These are the albums I return to again and again.

The Beat of My Heart, 1957: Bennett’s first foray into jazz with jazz drummers Chico Hamilton, Jo Jones, Billy Exiner, Art Blakey, Candido Camero and Sabu Martinez. Trumpeter Nat Adderley and tenor saxophonist Al Cohn also contribute on the project. The album aptly demonstrated Bennett’s instincts for improvisation to skeptical jazz critics.

Tony Bennett Sings For Two, 1961: An intimate piano-vocal studio recording with Ralph Sharon at the keyboard. Without orchestrations, Bennett’s voice and his interpretive skills are on full display. Bonus: this bare-bones album infuriated Columbia A&R chief Mitch Miller, best known for his schlocky “Sing Along With Mitch” LPs.

My Heart Sings, 1961: A joyous swinging big band record featuring saxophonist Zoot Sims, Eddie Costa on vibes, Milt Hinton on bass and future “Tonight Show” band leader Doc Severinsen on trumpet. One of the many highlights is Bennett’s powerful interpretation of Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill’s ballad “My Ship.” It’s rare that meatballs have ever been rolled and submerged into a pot of simmering Sunday gravy in our house without this playing.

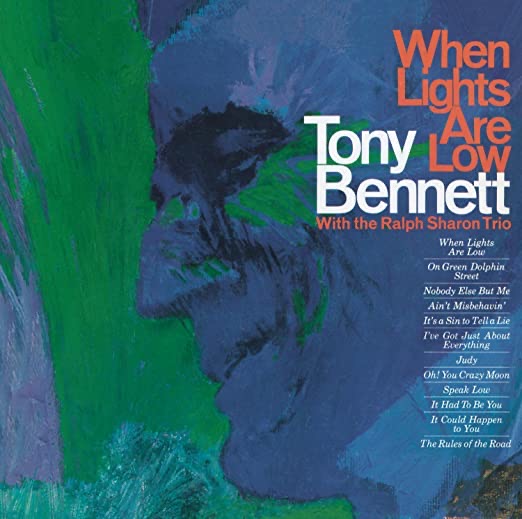

When Lights Are Low, 1964: Bennett’s first jazz trio record with pianist Ralph Sharon remains perhaps my favorite of all the singer’s many albums. I even dedicated an entire tribute to it during the COVID pandemic lockdown. As the title, taken from Benny Carter’s ballad, indicates, it’s a mood record perfect for a quiet evening at home, relaxing. Bonus: Bennett caught hell from the Columbia art department for commissioning illustrator Bob Peak to do the cover portrait. In his memoir, Bennett recalled the head of the art department grousing, “If the artist starts telling us what to put on the album cover, I’m out of here.”

Perfectly Frank, 1992: The singer’s tribute to longtime friend and mentor Frank Sinatra. Recorded with his longtime pianist Ralph Sharon and a jazz trio, Bennett wisely avoids Sinatra’s signature numbers and digs deep into his catalog, reimagining the songs from the Great America Songbook. Clocking in at 73 minutes, it’s also one of Bennett’s longest studio recordings.

Bennett Sings Ellington: Hot & Cool, 1999: Recorded to commemorate the centennial of mentor and friend Duke Ellington’s birth, “Bennett Sings Ellington” is one of the singer’s lushest, most tragically overlooked later recordings with arrangements by Jorge Calandrelli featuring the Ralph Sharon Quartet, jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis and a full orchestra.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.