In a Global Pandemic, Evan Lowenstein’s Stageit Offers Out of Work Artists and Fans a Safe Space to Connect

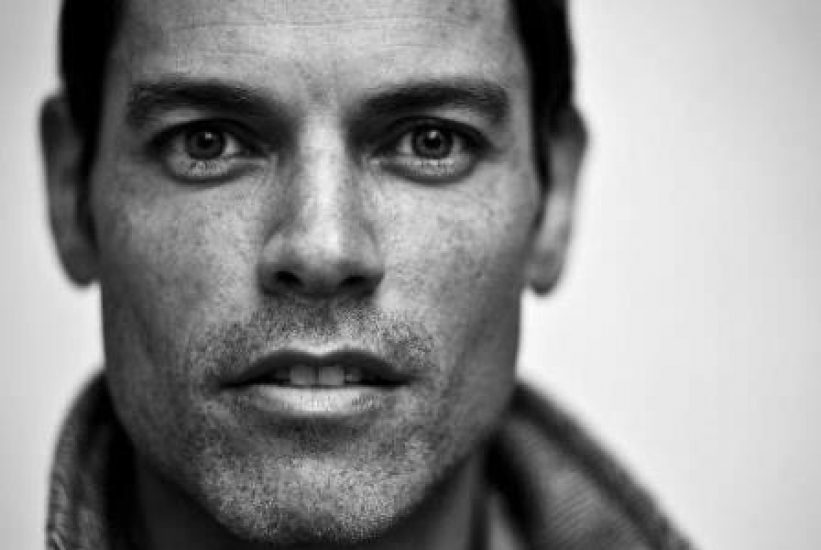

This week, Stageit founder and CEO Evan Lowenstein knew his 10-year-old digital concert streaming platform had scaled an unparalleled peak of success when PayPal suddenly shut down his company’s account. “They flagged us for suspicious activity,” the native Atlantan explained to Eldredge ATL while sheltering in place from his home in London Tuesday. Eventually, Lowenstein was able to convince the digital money transfer business his company hadn’t been hacked but, rather, was rapidly experiencing some unprecedented growth. “In a crazy way, I understand it,” he says laughing. “We’ve gone from having 75 shows scheduled on the site for the rest of this month to over 50 a day.”

Welcome to the perils — and the perks —of running a worldwide streaming performance platform in the time of a global pandemic when nearly the entire world is stuck indoors and live performers across that world are suddenly unemployed.

Billed as “a front row seat to a backstage experience” with celebrity investors including Jimmy Buffett, Lowenstein’s company was launched with great fanfare at SXSW in 2011. Major artists, including Buffett (who once raised $20,000 for charity in 20 minutes on Stageit), the Indigo Girls, Trey Songz, Sara Bareilles, Jackson Browne (who, on Wednesday, announced he had tested positive for coronavirus), George Clinton and Bonnie Raitt have all performed sets on the site.

But Stageit, originally conceived as a way for artists to connect with fans via intimate 30-minute online concert experiences where musicians and listeners can interact together, never took off the way Lowenstein intended. As our app-choked digital universe continued to expand (sometimes hourly), artists had a variety of streaming platforms from which to choose, including Facebook and Instagram with millions of users compared to Stageit’s dedicated but smaller 500,000.

Late last year, Lowenstein plotted a fresh course for Stageit’s success, shifting the digital company’s focus to the “green revolution” by appealing to artists wanting to reduce their carbon footprint, who instead of touring, could use the platform to offer unique up close performance experiences to fans from home.

But as COVID-19 began swiftly moving across the world early this year, Lowenstein took note and wondered if Stageit might become a tool for performers to safely connect with fans. On March 8, Lowenstein wrote an email to investors, basically saying, “This coronavirus thing looks serious. There might be an opportunity here for Stageit to help out artists if they can’t perform live in physical venues.”

And then, crickets.

Lowenstein, who hasn’t taken a salary from Stageit in years, says he wasn’t even logging onto the site daily when everything suddenly changed on Friday, March 13. “The site just went crazy,” says Lowenstein. “We’re doing 50, 60 and 70 shows a day right now. Last week alone, we did $400,000 in revenue. We made a little over $500,000 last year. The response has just been incredible. I’m just happy we had this platform up and running and in place when artists needed it.”

While Lowenstein is monitoring things in London, he’s communicating regularly with Stageit director of artist relations Nick Cox, who’s heading up the company’s operation in Los Angeles. “It’s really been a godsend having people in different time zones,” Lowenstein says. “I’m awake when everyone on the west coast is asleep and when I get up at 5 am here, I’m looking at artists from Australia, Poland and Madrid, Spain doing shows live on Stageit. We’re almost a 24-hour site just like CNN right now.”

By raising artist payout percentages from 60 to 80-percent during the global pandemic, Lowenstein and Stageit have become overnight working class heroes to struggling artists, who have had their livelihoods abruptly cut out from under them as public venues shuttered and months and months of scheduled gigs — and income — have evaporated overnight.

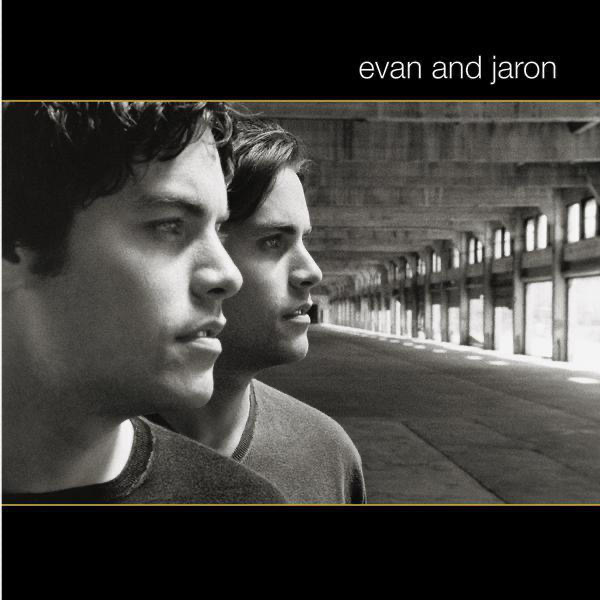

As one-half of the Atlanta acoustic duo Evan & Jaron, who got its start on stages across our city in the 1990s before signing with Columbia Records and landing the Top 20 hit, “Crazy For This Girl” in 2000, Lowenstein, now 46, knows first-hand the importance of offering artists a living wage, a state-of-the-art work space and the chance to interact with anxious fans in a time of global uncertainty.

“Starting out in Evan & Jaron in Atlanta, I know exactly how it feels to get the shittiest slot on the bill and walk out splitting 50 bucks,” he says. “I always want Stageit to be the polar opposite of that. We switched up the business model right now because the people who need the money the most, need to be getting the most.”

And while Stageit’s standard policy has been to pay artists within seven to 10 days of their gig, the company has now brought in extra help to ensure performers are paid within three days or faster.

During the pandemic, Stageit is also offering financially secure bigger acts the opportunity to book shows as a part of its Stageit Local initiative, where they can play gigs to raise money for local musicians, restaurants and bars that have all be financially decimated by the novel coronavirus pandemic.

“We all started out as local artists,” Lowenstein explains. “If you’re a financially secure musician who can go online and ask fans to donate, do it to give back to these communities that supported you starting out. I don’t even care if you use Stageit. Use Facebook or whatever you want, just donate the proceeds of your performance to someone local who’s in need right now. It’s heartbreaking to see so many people being simultaneously affected by this crisis.”

Lowenstein’s one request of these well-intentioned bigger artists? “Just don’t play for free. That can really hurt the smaller artists. If you donate your time to play right now, give the fans a chance to tip you or to donate to those in need.”

Even Evan Lowenstein himself dusted off his guitar and the chords to “Crazy For This Girl” and went live on Stageit this week from London to check in with friends and fans and to donate the money generated from his set to other Stageit artists in need. “I have so many live artists right now, people I’ve known for years asking me, ‘Evan, why didn’t you force me to do a Stageit set years ago?’ They’re seeing the way to use this to connect. It’s like how we’re all discovering right now, hey, that meeting really can be a phone call. We’ve hit this inflection point but it’s bittersweet because the world is suffering so much.”

Quarantined companies are even booking business classes on the platform and Stageit is the official streaming platform for the upcoming Digital Dragfest 2020 taking place on the site March 27 to April 12, featuring drag performers from across the country whose clubs are currently shuttered. “So many of the Dragfest shows are sold out, it’s incredible,” says Lowenstein. “They’re selling hundreds of tickets at $10 each and then adding second shows!”

Before hanging up, Evan provides a quick update on his twin brother Jaron, who is currently safe with his family in Los Angeles (these days, Jaron is busy managing both the global musical phenomenon Post-Modern Jukebox started by pianist and arranger Scott Bradlee and New York Times best-selling author and “Making Sense” podcast host Sam Harris).

As Evan Lowenstein continues to parent Stageit through this unplanned growth spurt, he’s hopeful his little start up ends up occupying a permanent place on artist gig calendars once the world reopens.

Says Lowenstein: “So many performers are being introduced to Stageit right now because they’re being forced to move performances online. I’m hopeful they’ll remember how we supported them and how they were able to connect with fans in a meaningful way and raise some much-needed cash. Maybe they’ll consider how to integrate Stageit into their overall performance schedules. But instead of three shows online a week, maybe it’s one a month or one a quarter with us.”

“No matter how this all turns out, it feels good to know Stageit was there when artists needed us in this moment and we were able to offer a global stage when performers needed one.”

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.