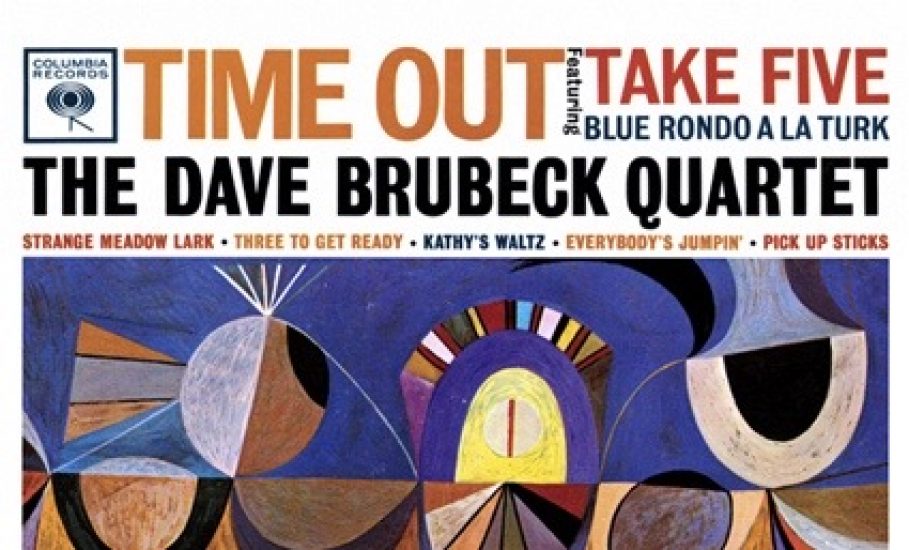

From Civil Rights Struggles to a Red Cross Windfall: The Surprising History of Dave Brubeck’s ‘Time Out’

Thanks to Stephen A. Crist, professor of music history at Emory University, 61 years after its release, jazz fans finally have a painstakingly researched, behind the scenes examination of the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Time Out,” the groundbreaking jazz LP first released in 1959. And Brubeck listeners might just have Johann Sebastian Bach to thank for the tome, since it was the German composer who first brought Crist and Brubeck together back in 1998, when Crist interviewed the jazz pianist for research he was doing on Bach.

While Miles Davis’ equally iconic and best-selling Columbia Records 1959 masterpiece “Kind of Blue” has warranted a pair of book-length examinations by Ashley Kahn and Eric Nisenson, after attending Brubeck’s public memorial at The Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine on May 11, 2013 in New York City, it dawned on Crist that no such book existed on “Time Out.”

“Nobody had done a serious, scholarly study of Brubeck and I was animated, of course, by writing about ‘Time Out,’ because it was the most important project of Dave’s career,” explains Crist. “It’s one of the best-selling jazz albums of all time. Everybody knows it, even if you don’t know it, you know it. It’s been a part of American culture ever since it appeared in late 1959.”

Like Columbia labelmate Davis’ best-selling adventure in modal jazz recorded and released the same year, Brubeck’s LP-length experiment creating jazz in complicated time signatures usually alien to the art form, was an unexpected hit with the public. Today, both albums are so beloved, even the most casual of jazz listeners likely own copies of each. To date, “Kind of Blue” has achieved quadruple platinum sales status (four million copies have been sold) while “Time Out” has gone double platinum (sales of over two million units).

While Brubeck himself was no longer around for Crist to talk to, he left a small mountain of recorded interviews, papers, the original album compositions and even his own tapes from the famed summer 1959 “Time Out” recording sessions, all housed until recently at the University of the Pacific Library in Stockton, California. Brubeck family members, including his widow Iola, son Darius and daughter Catherine (who inspired the album’s “Kathy’s Waltz”) all pitched in to help during Crist’s six years of research and writing. The author also had access to Columbia Records A&R rep. and producer George Avakian’s papers (who signed Brubeck to the label in 1954) and the archives of Brubeck’s longtime Columbia producer Teo Macero, both housed at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Whether you’re a longtime Brubeck aficionado or your exposure to “Time Out” has been limited to the album’s famous track “Take Five” being used in multiple car commercials, there are fascinating revelations aplenty in Crist’s book and it is a must-have addition to any serious jazz listener’s library.

Alongside insights from Crist, here are six things you might not know about the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s most famous LP.

- Dave Brubeck Was a Social Justice Warrior

The jazz pianist had worked hard to assemble his world-famous quartet of alto saxophonist Paul Desmond (who once famously quipped that the sound he strived to create was the audio equivalent of “a dry martini”), the Kansas City inspired bassist Eugene Wright and time signature defying drummer Joe Morello. On the heels of the release of “Time Out,” which was flying off record shop shelves by early 1960, Brubeck’s booking agency had arranged a lucrative 25-date tour of the American South for the quartet.

There was just one issue — Eugene Wright happened to be a black bassist in an otherwise white act. With $1,500 per gig on the line, Brubeck received a pointed missive from a rep at his booking agency. Recalls Crist: “The letter is in Dave’s papers and it basically said, ‘Look, you’ve got these dates coming up, there’s a lot of money on the line and you know perfectly well that these southern colleges won’t accept a mixed band. Would you please just use a white bass player?’ He was really pressuring Dave. At the bottom, in capital letters and underlined, he wrote, YOU NEED THIS!” Of course, Dave’s answer was ‘Hell no. I wouldn’t do it for a million dollars.’” All but three of the shows were nixed.

A year earlier, a gig at the University of Georgia was also cancelled. The young fan who went to bat for the band with the college administration but was told in no uncertain terms that he would not be presenting Brubeck’s mixed-race band on campus? Future New York Times best-selling novelist Stuart Woods. The writer agreed to be interviewed for Crist’s book. “He sent his cellphone number immediately and said, ‘I’d be happy to tell you the whole story,’” says Crist. “And he did! It was very illuminating.” Meanwhile, Paul Desmond slipped in a final acerbic word on the controversy, slyly inserting a lick of Artie Shaw’s “Nightmare” into the quartet’s recording of “Georgia on My Mind” on the quartet’s 1959 “Gone With the Wind” LP of southern standards.

2. Even the Dave Brubeck Quartet Relied on a Little Studio Magic

While it was attempted multiple times in studio, even on the released version of the track “Blue Rondo a la Turk” careful listeners can make out a missed note by Brubeck and a squeak by Desmond on the complicated completed track. But for Crist, the real revelation was discovered while listening back to Brubeck’s own recording of the album’s ballad “Strange Meadow Lark” among his papers. Says Crist: “I discovered this tune I’ve listened to a million times, is spliced! I realized that even Dave was never able to play that beautiful ballad introduction and then make the transition with the band. So, they got a really good take with the band and then went back and re-recorded the introduction and spliced it together. It’s done so artfully you can’t tell. You have to go back and listen to those recordings in order to hear it.”

3. There’s an Unpublished Brubeck Autobiography

One big surprise for Brubeck devotees scouring the pages of “Dave Brubeck’s Time Out” is the quoted material from an unpublished autobiography manuscript written over the years by Dave and Iola Brubeck. “Iola worked at it for years and years,” says Crist. “I remember when she came to Atlanta for a Brubeck festival back in 2002, she was well into it then. She said she was writing it primarily for the family, just to pass on to them. I never saw the whole thing, but over the years, she sent me extracts from it. It must be hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pages. The family has the manuscript. I wouldn’t be surprised if it sees the light of day at some point.”

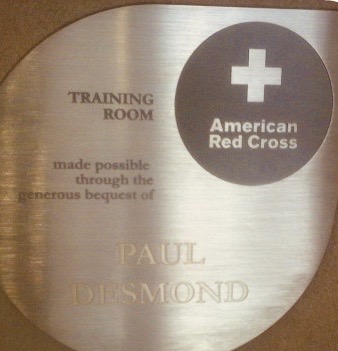

4. Thanks to “Take Five” Royalties, The American Red Cross Has Benefitted to the Tune of $6 Million

Near the end of his life in 1977, Paul Desmond, the composer of “Take Five,” “Time Out’s” most famous track, a dedicated bachelor and lifelong chain smoker, was persuaded by his attorney Noel Silverman to make out a will. Says Crist: “My understanding is Desmond didn’t have heirs and didn’t really have a plan so when his attorney told him he kind of needed to have a plan, Desmond offhandedly replied, ‘OK, let’s go with the Red Cross. They’re a good outfit.’ There’s even an American Red Cross training room [at its national headquarters in Washington D.C.] named after Desmond.” Royalties from the jazz saxophonist legend have now raised in excess of $6 million for the charity.

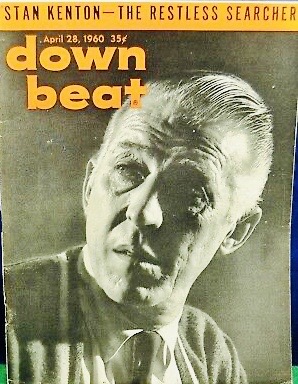

5. Downbeat magazine’s Original Review Trashed “Time Out”

While jazz critic Ira Gitler might now be best known for the many liner notes he contributed to classic recordings, including John Coltrane’s “Soultrane album, in 1960, he shocked Brubeck admirers by giving “Time Out” a rating of fair in the April 28, 1960 issue of the jazz bible, Downbeat. Writing that Brubeck “has been palmed off as a serious jazzman for too long,” Gitler then proceeded to go after Joe Morello’s extended drum solo in “Take Five,” writing that it resembled “the accompaniment for a troupe of trampoline artists.” (Gitler died in 2019). Says Crist: “It was a thorough trashing. I did write to Ira Gitler in the process of writing the book but I never heard back. I basically wanted to know, ‘Any new thoughts on this?’ But he essentially answered that question in Hedrick Smith’s [2001 PBS] documentary [“Rediscovering Dave Brubeck”] when he stated, ‘No, I haven’t really changed my mind. I don’t think this is the essence of jazz.’ While Gitler didn’t like ‘Time Out,’ he didn’t totally write off Brubeck. He just didn’t like this particular album.”

6. There are Four “Time Out” Sequels

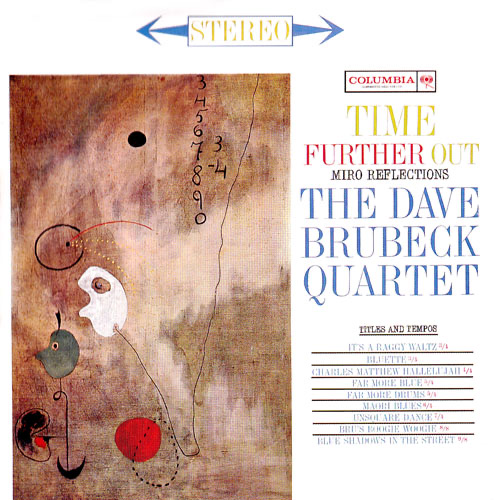

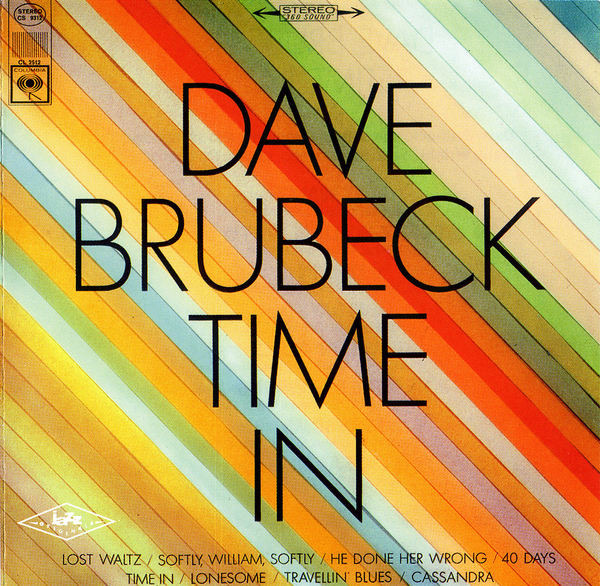

Among the Brubeck papers Crist cites in “Dave Brubeck’s Time Out,” the jazz pianist made no bones about wanting to become “a top name in American jazz.” After signing a contract with Columbia Records and landing on the cover of Time magazine in 1954, Brubeck and the quartet became one of the most financially successful jazz acts in America. So when the public started snapping up copies of “Time Out,” Brubeck immediately began thinking about recording a series of time signature-centered sequels, including 1961’s “Time Further Out,” 1962’s space race themed “Countdown: Time in Outer Space,” 1964’s “Time Changes” and finally, “Time In,” in 1966, one of the final studio sessions the Dave Brubeck Quartet recorded before splitting up with a final show on December 26, 1967, after a successful 16-year run, nearly unheard of for a jazz quartet.

Says Crist: “Dave was totally aware of the commercial considerations of recording sequels to ‘Time Out.’ Once the album took off, it was, ‘Let’s do more!’” So, which of the sequels does Crist routinely play? “The honest truth is I don’t play any of them right now because I did such a deep dive into them while writing the book,” Crist concedes with a laugh. “There are certain cuts I come back to, like on ‘Time In,’ I love the track ‘Cassandra.’ It’s not one of the time experiments but it’s a great tune.”

Emory University professor Stephen Crist’s book “Dave Brubeck’s Time Out,” the latest in the Oxford Studies in Recorded Jazz series, is now available.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.