Live & Uncensored! A Conversation with Keisha & Millie Jackson

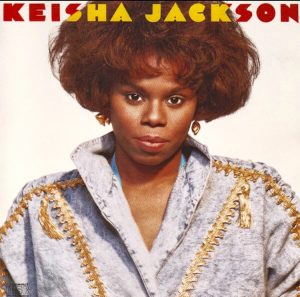

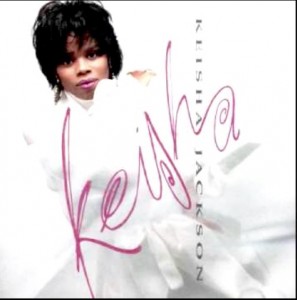

Eldredge ATL November Guest Editor Atlanta singer and recording artist Keisha Jackson tried her best to stay out of the family business. But when you’re the daughter of legendary soul singer and Atlanta resident Millie Jackson, that can be difficult. After briefly pursuing an entertainment law career, Keisha gave in to genetics and recorded a pair of albums for Sony Music.

Eldredge ATL November Guest Editor Atlanta singer and recording artist Keisha Jackson tried her best to stay out of the family business. But when you’re the daughter of legendary soul singer and Atlanta resident Millie Jackson, that can be difficult. After briefly pursuing an entertainment law career, Keisha gave in to genetics and recorded a pair of albums for Sony Music.

Over the years, she’s worked with Atlanta producers L.A. Reid, Kenny “Babyface” Edmunds and contributed background vocals to the recordings of Aretha Franklin, Toni Braxton, Whitney Houston and Joss Stone. She’s toured with Erykah Badu, Angie Stone, George Clinton and in 2014, was a featured vocalist on the 40-city 20th anniversary Outkast tour with longtime pals Andre 3000 and Big Boi. In addition to serving as CEO of her own company, One Voice Entertainment, Keisha is currently working on a new solo R&B and blues album.

In their first-ever joint interview exclusively for Eldredge ATL, Keisha Jackson and her mother, ground-breaking, taboo-busting R&B legend Millie Jackson sat down together to discuss two generations of strong independent women carving out two very unique niches in the R&B industry.

Eldredge ATL: Millie, when did you know you had a singer on your hands?

Millie Jackson: I started getting these reports back to me when she was in college [at University of Bridgeport in Bridgeport, Conn]. She always told me she was too scared to go on stage. Then I find out she was the official “Oh say can you see?” national anthem singer for the college basketball team!

Eldredge ATL: So Keisha, your secret life was exposed.

Keisha Jackson: Actually, it was only a secret from my mother! (Millie laughs). When I was growing up, mom always stressed that she didn’t want me involved in the business so I tried to keep it quiet from her. I honestly tried to do something else career-wise until it became so obvious to me that this was what I was going to do that I put a halt to everything else. I was doing it on the side, I was singing the national anthem at games and I had little groups that I was singing in at school. I didn’t tell my mother because she was always talking about how hard the business was.

Millie Jackson: I wanted you to become an attorney. We needed a lawyer in the family to keep the money! (laughs). It’s a hard life and I didn’t have an education, really. I got through high school by going at night. I thought, since I could pay for it, someone in the family needed to go on and do better than I did.

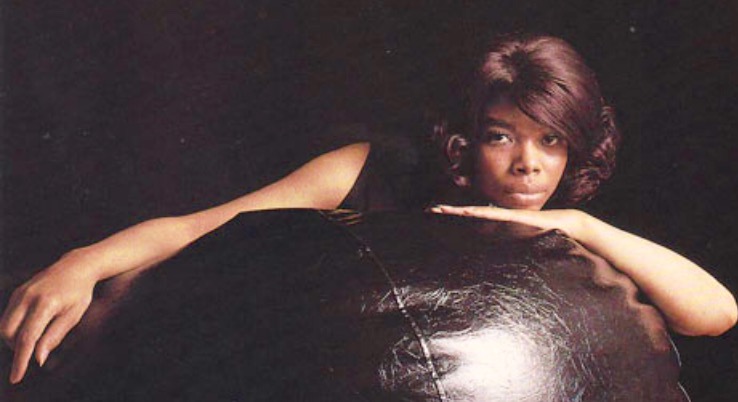

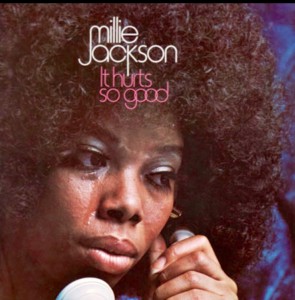

Eldredge ATL: Millie, you’re looked at as a strong independent feminist role model who came up in a male-dominated music business in the early 1970s. How difficult were those early days?

Millie Jackson: For the first five years of my career, I just played crazy. (laughs). They couldn’t figure me out and I liked it that way. Every day I would get off of my day gig and go by the record company, which was a few blocks away. I would sit there and cut up and act crazy in order to learn the business and find out what was going on. I started recording and having hits. Later, when my five-year contract was up, they wanted to offer me a $50,000 bonus to re-sign [with Spring Records]. That’s when I went out and found the most expensive music lawyer in the business and had him renegotiate my contract. You had to look out for yourself, especially as a woman.

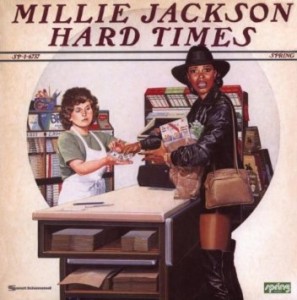

Eldredge ATL: Your career, spanning from writing “A Child of God (It’s Hard to Believe)” on your 1972 debut album, the song “Hypocrisy” for the “Hurts So Good” album in 1973, the two “Caught Up” albums in 1974 and 1975, your “Live & Uncensored” LP in 1979 and the satirical Norman Rockwell painting of you in the grocery store check out counter on the cover of your 1982 “Hard Times” album was all about communicating important societal messages to your listeners. How did that social commentary become so engrained in your work?

Believe)” on your 1972 debut album, the song “Hypocrisy” for the “Hurts So Good” album in 1973, the two “Caught Up” albums in 1974 and 1975, your “Live & Uncensored” LP in 1979 and the satirical Norman Rockwell painting of you in the grocery store check out counter on the cover of your 1982 “Hard Times” album was all about communicating important societal messages to your listeners. How did that social commentary become so engrained in your work?

Keisha Jackson: The “I Had To Said It” album too.

Millie Jackson: Right. Truth is, I never set out to do any of that. I was just writing songs and deciding to record them. It wasn’t about being a leader of anything. I was about communicating how I felt, saying what was on my mind at the time.

Keisha Jackson: For me, that’s such a big difference between the soul music back then and now. These days, those themes, those topics are found in rap music. People back then sang about the times, they sang about their own experiences.

Millie Jackson: The Curtis Mayfields, the Marvin Gayes.

Keisha Jackson: Right. And of course, Stevie Wonder. Today, that’s not in our R&B music. Today, R&B and soul music really just focus on love and heartbreak. But what they’re not speaking of are their specific situations. But rap music has picked up those topics and is addressing them for today’s listeners. That’s a huge difference between her generation and mine. Soul singers today are not tackling those kinds of issues in their songs. Nobody’s taking those kinds of risks now.

Keisha Jackson: Right. And of course, Stevie Wonder. Today, that’s not in our R&B music. Today, R&B and soul music really just focus on love and heartbreak. But what they’re not speaking of are their specific situations. But rap music has picked up those topics and is addressing them for today’s listeners. That’s a huge difference between her generation and mine. Soul singers today are not tackling those kinds of issues in their songs. Nobody’s taking those kinds of risks now.

Millie Jackson: Today’s soul singers are playing it safe.

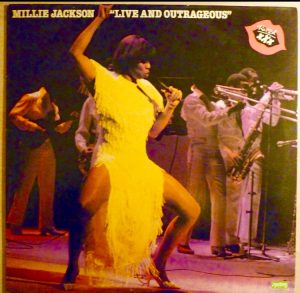

Keisha Jackson: Exactly. As I got older, I began to appreciate what my mother did. I recognized the importance of speaking out. As a kid, sometimes it was embarrassing. Nobody else’s parents were saying those things and they certainly weren’t going on stage and singing about them. The good thing was, where I was being raised in Teaneck, [New Jersey], I was surrounded by a musical community that was committed to talking about those same issues. But when you were in elementary and junior high and going to school with regular kids, it could be tough having Millie Jackson as your mom. The other kid’s moms weren’t on the cover of her “Live and Outrageous” album with the gown split up the sides and your mom is squatting. There were times when I felt like I had nothing in common with the other kids. I had a long awkward stage. And then when I finally came out of it, I was almost Millie Jackson, Jr. I embraced it.

Keisha Jackson: Exactly. As I got older, I began to appreciate what my mother did. I recognized the importance of speaking out. As a kid, sometimes it was embarrassing. Nobody else’s parents were saying those things and they certainly weren’t going on stage and singing about them. The good thing was, where I was being raised in Teaneck, [New Jersey], I was surrounded by a musical community that was committed to talking about those same issues. But when you were in elementary and junior high and going to school with regular kids, it could be tough having Millie Jackson as your mom. The other kid’s moms weren’t on the cover of her “Live and Outrageous” album with the gown split up the sides and your mom is squatting. There were times when I felt like I had nothing in common with the other kids. I had a long awkward stage. And then when I finally came out of it, I was almost Millie Jackson, Jr. I embraced it.

Millie Jackson: And I was always on your case about not being like me, too. I remember one day when I had the “[Phuck U] Symphony” out [on the 1979 “Live and Uncensored” album] and I caught her walking through the house singing it and I remember yelling, “What are you singing?!” And she said, “Nothing. I just like the music.”

Keisha Jackson: OK, so this is the thing. You’re going to pick up things from your environment. It’s all about what you’re exposed to. That’s what helps to build your character. It’s what I heard everyday because that was her new song and it was everywhere. It was inevitable that it would get stuck in my head. I did know that it wasn’t appropriate to sing. So I hummed it. (both laugh).

Eldredge ATL: OK, Keisha, be honest. Growing up in Millie Jackson’s house, a performer who broke barriers to become one of the most explicit R&B artists to ever grace a stage, did she have rules about words you couldn’t say in the house?

Keisha Jackson: I would say yes, absolutely. But it was never explicitly stated. It was just understood. I knew what was proper and what wasn’t.

Eldredge ATL: Millie, were there words that were off limits in the house?

Millie Jackson: Not for me!

Keisha Jackson: (laughs) That is entirely accurate! My friends were all into smoking and cursing and I just wasn’t into all that.

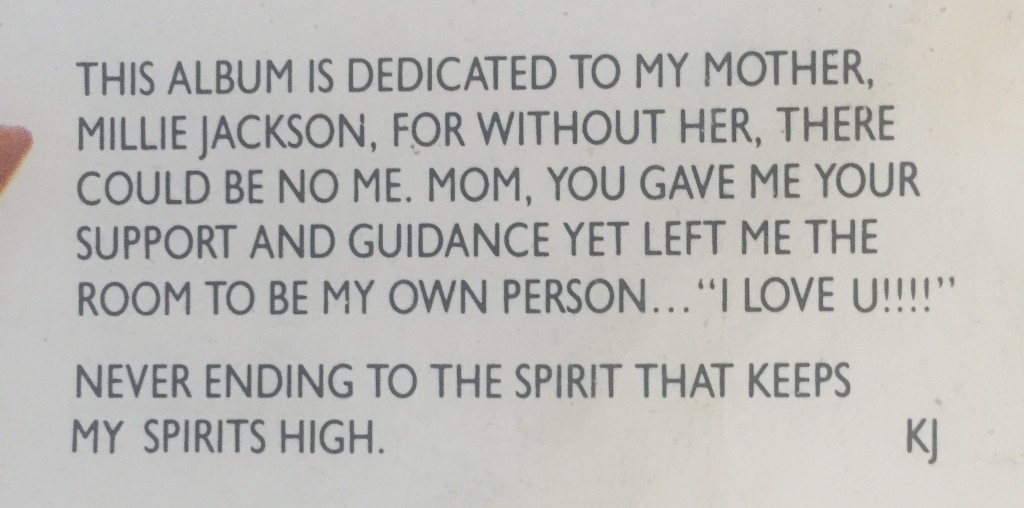

Eldredge ATL: Your 1989 debut album, “Keisha Jackson” is dedicated to your mom. You wrote: “She gave me support and guidance but she left me room to be myself.” How did she do that?

Millie Jackson: Easy. I yelled “I’ll kill you if you do that!” a lot! (laughs)

Keisha Jackson: When I got signed, I wasn’t looking to be signed, I wasn’t looking for a deal. I had recorded some demos for the song “Hot Little Love Affair.” It was supposed to be submitted for Diana Ross. The label heard it and said, “We want the girl who is singing.” They had no idea the girl was Millie Jackson’s daughter. It was, “We just like the way that girl sounds. Sign her.” I went to my mother and said, “I have this deal” and we briefly discussed her managing me. But we mutually agreed that wasn’t going to work, personality-wise. As a result, she granted me the freedom to make my own decisions. She didn’t go into mom overdrive. She always offered advice but often the best advice I took from her wasn’t what she was offering. It was watching her throughout her career and learning from her how to handle your business. I saw what to do and what not to do.

Keisha Jackson: She would call me up on stage to perform to with her. I’d be like eight or 10 years old, sitting in the wings of the Apollo Theatre and she would call me up to adlib on any song she happened to be doing. It was never the same song, never the same part twice! It was just on a whim. I felt like someone punched me in the chest because I knew it was coming. I was completely and totally paralyzed. I hated it but I loved it at the same time. I mean, she would do it in the middle of “Hurts So Good,” which was completely inappropriate, given my age (Millie laughs). It was awful.

Millie Jackson: It wasn’t awful because you always did good, you always rose to the challenge. She knew music and she could adlib like nobody’s business. Plus, she could do these incredible runs that I couldn’t even think about being able to do. She had technique. I was just so proud. I don’t think I’m the greatest singer in the world. When I started out, I was scared to death because I had no training. That’s the whole reason I started talking crap in my act in the first place. But this girl can really sing.

Keisha Jackson: It taught me how to think on my feet and I learned how to improvise on stage, which was incredibly important. It was on the job training.

Keisha Jackson: The “sh*t-talking” family legacy? Not very.

Millie Jackson: What did you just say? (laughing)

Keisha Jackson: You heard me. (Millie laughing). It’s more important for me to teach my kids to say how you’re feeling. It’s important to be honest. It’s important to be heard. Your voice is really important. It’s about being forthright and real. That’s the family legacy that I want to carry on.

Editor’s note: A few minutes after Keisha’s conversation with her mother concluded, she called back to discuss an incident from her childhood that would shape her life and how she viewed her mother. In the early 1980s, Millie Jackson traveled to South Africa to perform a set of concerts, unaware of the looming political powder keg of apartheid.

When she finally got home, the people in this country were boycotting her for going to South Africa! They were boycotting her shows and her music, picketing out in front of Carnegie Hall and at the Apollo. I was scared for her. Finally [in 1984], she went in front of United Nations with a bunch of other recording artists [as a guest of Ambassador Oumarou Youssoufou, executive director of the Organization of African Unity] to announce she wouldn’t return to South Africa. After she returned to the U.S., the people boycotting her in her own country had no idea that she had, in fact, refused to play to a segregated audience in South Africa. She went to the U.N. and said her piece.

That was a key moment for me as a kid. It told me a lot about her strength of character and about who my mother was. I was very proud of her. She stood up for what she believed and she stood up for her people. She doesn’t tell that story. But it made a huge impression on me. My mother has always been a strong woman. She rarely cries. She steps up to the plate, whether it’s difficult or not. She gets the job done. I want people to know that story about her. It makes me very proud to be like her and to be her daughter.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.