‘I’m a Storyteller’: Terry Burrell on Bringing Billie Holiday to Life in ‘Lady Day’

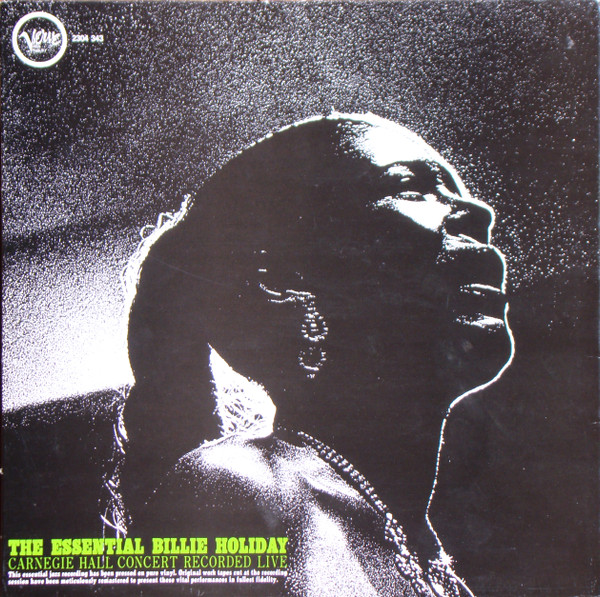

She emerges on stage, broken and boozed up. The members of the jazz trio behind her nervously exchange glances in the dark. And by the time she’s finished her opening number, “I Wonder Where Our Love Has Gone,” her eyes are brimming with tears. Welcome to Emerson’s Bar and Grill, Philadelphia, 1959. Inexplicably, at just 44, time is running out for Billie Holiday, one of the world’s greatest jazz singers. As New York Times arts critic Gilbert Millstein would later write in the liner notes for “The Essential Billie Holiday Carnegie Hall Concert” issued by Verve Records in 1961: “She had been strikingly beautiful but she was wasted physically to a small, grotesque caricature of herself. The worms of every kind of excess — drugs were only one — had eaten her.”

On stage through June 26 at Theatrical Outfit downtown, Atlanta actress Terry Burrell once again brings to life “Lady Day At Emerson’s Bar & Grill.” It’s a harrowing, deeply moving and achingly beautiful 75-minute tour de force with no intermission and no opportunity to run for the exits for a cold glass of pinot grigio when the shit starts getting real onstage. From the first piano chord, Burrell, aided by the expertise of musical director and pianist Tyrone Jackson, bassist Ramon Pooser and drummer Lorenzo Sanford, plunges herself head-long into the material, with zero emotional guard rails in place. Now, 63 years after an American icon strained to hit her final note, “Lady Day” allows us to time-travel back and experience Holiday in all of her complexities and genius one last time.

The play by Lanie Robertson (which premiered at Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre in 1986 and later won Audra McDonald a Tony Award for the role in 2014) and directed for Theatrical Outfit by Eric J. Little offers audiences a front-row seat to the American tragedy that was the end of Billie Holiday’s life, just before her July 17, 1959 death, shackled to a hospital bed at New York’s Metropolitan Hospital where she had been arrested for illegal possession of narcotics. A performer who had scaled the heights of Carnegie Hall but by the end, played New York City’s East Village Phoenix Theatre on May 20, 1959 for $350.

It’s a powerful, lingering piece of theatre that Burrell first brought to the Theatrical Outfit stage in 2018 and has brought back to close out the 2021-2022 season. As TO artistic director Matt Torney explains in his program note: “As we were considering plays for a season following a global pandemic, there was something about Billie’s story and the bruised beauty of her music that just felt right. Though we have all lived through pain and heartache, life and art sing on.” When Burrell sings Billie’s still-shocking “Strange Fruit” about “Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,” it resonates more fully in a space that was formerly Herren’s restaurant, the city’s first white-owned restaurant to voluntarily integrate in 1963. It’s even more powerful performed in a theater down the street from where protesters of all colors marched following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in 2020.

In the following conversation with Eldredge ATL, Terry Burrell discusses getting into the mental and emotional headspace of Billie Holiday’s final days each night, how she vocally plays the role and the enduring life lessons Holiday’s tragic life still have to teach us in 2022.

Eldredge: You played this role at Theatrical Outfit in 2018. I’m wondering how this material has changed for you since the pandemic and the murders of Ahmaud Arbery here in Georgia and the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020. This piece really speaks to the challenges we still face on race in this country.

Burrell: It does. This is what people like Billie Holiday were talking about for decades. For a lot of folks, whites in particular, both here in America and in Europe, after a while, people don’t want to hear about it anymore. It’s “You know what? I didn’t do it. It’s that same old song again.” I believe the universe is intelligent. Everything it does has a purpose. Everything in its right time. Nobody would have seen what folks like Billie Holiday had been talking about if there had not been a pandemic and everyone had to be home. People watched a murder take place right before their very eyes. A murder by someone who is paid to protect us, all of us as American citizens. The entire world saw it and we were disgusted by it. That’s the stuff my grandfather lived with. It was horrific.

Eldredge: I was watching the audience reaction last night as you performed “Strange Fruit.” In 1999, Time magazine named it “The Song of the Century,” for all of its powerfulness and painfulness. How do you get yourself into a mindset to be able to sing that in each performance?

Burrell: I’ll tell you the imagery in my mind when I’m singing that song. It’s a story my uncle shared with me. When he was a boy in Florida, his father took him to an area of the woods Black folks called The Hammer. That was a place where the Klan would take Black men they were having a problem with. They would beat them, pour hot boiling tar on their skin and then dump feathers on them. When my uncle told me this story, the part that chilled me was he said on the trees, you could still see the scorch marks. When I’m singing that song, you have to get into a certain space, you cannot back away from it. You cannot think about how the audience is responding to it. I remember that story from my uncle and those souls and the torture they went through.

Eldredge: Billie Holiday had a completely distinctive singing style. But it’s fair to say it’s far removed from Terry Burrell’s. How did you get vocally into character?

Burrell: Interestingly enough, our vocal qualities are very similar. We both have “light” voices and having done a lot of musical theatre, I love using a lot of straight tone whenever I can. The thing I realized listening to her is how relaxed she is when she’s singing. She concentrates on the lyric even more so than the melody. She just relaxes and goes where the voice takes her. I don’t think Billie knew what she had when she first started. She wanted to sound like Louis’ [Armstrong] horn she wanted to have the sass of Bessie Smith but she didn’t have that same bigness in her voice. When she became older and sicker, when she was no longer singing for the love of it but singing because she had to survive and she understood what it was people wanted to hear, she began to do tricks vocally. That sound, that clip, that little spin she puts at the end of notes, she started over-exaggerating them. It was her way of saying, “I’m gonna give you this, this is the Billie you want.”

Eldredge: Two of my favorite vocalists of all time are Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, probably because they’re such a study in contrasts. Ella had perfect pitch and diction but was sometimes criticized for a lack of emotion. Technically, Billie sometimes sang behind the beat but put a lifetime’s worth of emotion into each song.

Burrell: She loved doing that. Someone once asked her in an interview, “Why do you sing such sad songs?” and she said, “I dunno, I’m just sad.” And she was. She was sad all the time. This was her therapy. She didn’t have a psychiatrist she could lie on the couch with. And here’s the thing — if she had been healthy mentally and emotionally, she wouldn’t be the Billie we know. This is what we respond to. During the pandemic so many people were able to be in touch with their sadness. When you’re busy, out in the world with work to do, you don’t think about yourself. What you really want or have the time to ask yourself “Is this really making me happy?” Now, you’re forced to shut everything down and deal with it. Billie gave us all the permission to be sad, to be in touch, up close and personal, with your own pain. And when it’s naked like that, as the listener, you no longer feel alone.

Eldredge: One thing that fascinates me about the setting of this piece is it’s right near the end. This is when she’s recording “Billie Holiday” for MGM Records and “Lady in Satin” for Columbia Records, both with arranger Ray Ellis. Her voice is completely destroyed by this point. Ellis went to take a drink of water from a pitcher Billie had in the vocal booth and discovered it was straight gin. What kind of headspace is required for you as an actor to step on the stage and bring this to life?

Burrell: There’s a technique that I learned a few years ago called brain spotting. It’s based on rapid eye movement. It’s form of hypnosis. I learned it when I performed “Lady Day” the first time. When I’m sitting there in the wings, I use it and it has never failed me. When I cast my eyes in a certain direction at a certain point, it is immediate. Terry can be sitting up straight and suddenly, my shoulders are slouched and I’m mumbling, “I don’t wanna go out there.” It gets me right into the space. When I hear that opening piano, I really don’t care. It’s easier for me now as someone who is older and who has lived life, to accept Billie. Not judge her, accept her. I can focus on the words and do it in a way that’s so open and so free, so unselfconsciously. I can’t think about what she’s singing or judge it in my head or I will never give it the kind of heft that it needs to have. And Billie herself wouldn’t have cared: “You don’t like what I’m singing? Leave.” At the end, she felt like nobody loved her. Nobody.

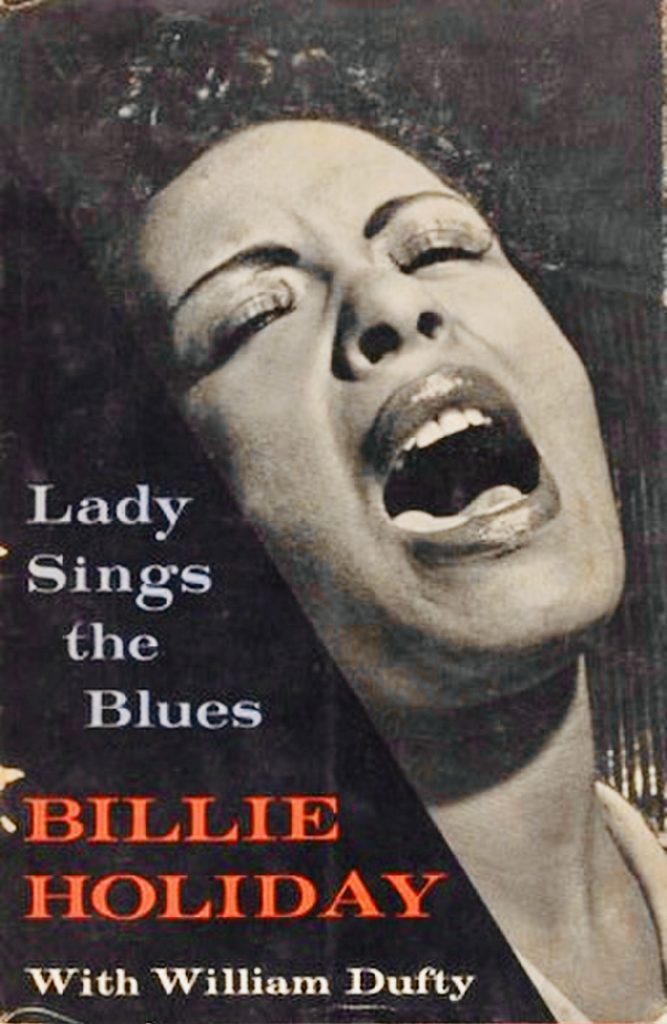

Eldredge: In “Lady Sings The Blues,” her 1956 autobiography, Billie Holiday discussed in detail the perils of singing with the Artie Shaw band in the South and the racism she encountered. There’s a powerful scene in “Lady Day” where you bring the reality of the mistreatment she endured in white-only establishments. What’s it like for you to bring that hard reality to audiences in 2022?

Burrell: I’m a storyteller. To me, that’s what I’m doing. It’s not Terry’s story, it’s Billie’s. It serves as a reminder that it wasn’t that long ago, that things were that way and in your face that way. She couldn’t walk through the front door. She had to eat in the kitchen. And here were these young white men who could have easily said, “That’s your deal, your fate.” Instead, they said, “We’re not walking through the front door either and if she has to eat in the kitchen, so do we.” I don’t mind being the conduit to reminding people that this happened and can still happen. Just look at politics today. If some people have their way, this could still be revived and we have to be guardians of that. And not just our generation, but the generations that are coming after us. Because the risk you run by not telling that story is people forget.

Eldredge: There’s a powerful moment in this show — a show filled with powerful moments — that really reflects the totality of what Billie Holiday went through. She returns to the stage clearly after shooting drugs and tells her pianist who’s been making excuses for her, “Let’s stop with all the fake doctor shit. I’m still an N-word. They ain’t cured me of that.” As a white person sitting in the audience, that moment powerfully demonstrates exactly what a lifetime of racism in America cost her.

Burrell: Exactly. It didn’t matter how famous she was or how many records she had recorded. None of that mattered, even in the eyes of some [of the whites] who came to see her. She was “entertainment.” They wouldn’t have her in their homes or be seen with her at dinner.

Eldredge: I would be remiss if I did not ask about your adorable co-star who plays Billie’s dog Pepi in the show.

Burrell: (laughs) Her name is Storm and I actually got her four years ago when I was doing the show because the script calls for a dog. They were talking about getting a shelter dog but I had been wanting a dog. My husband was paying me no mind. My niece heard me talking and said, “Auntie Terry, I have a dog I can’t keep.” She showed me a picture of Storm and she was so cute. For a year, this dog’s life was one thing and in the blink of an eye, everything changed. She’s in a house with people and smells she does not know. I just handled her, put her in the car and an hour later, she was at rehearsal with me. And now, once she hits that stage, I could sing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and it wouldn’t matter. All eyes are on that dog!

Terry Burrell plays Billie Holiday in “Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill” at Theatrical Outfit at 84 Luckie Street in downtown Atlanta through June 26. Go to theatricaloutfit.org or phone 678-528-1500 for details and tickets.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.