‘Judy’ is a Dazzling Technicolor-Hued View of Garland’s Dark Final Days

Fifty years after her passing, Judy Garland has now been dead longer than she was alive. This year marks the 50th anniversary of her accidental drug overdose at age 47 and the 80th anniversary of “The Wizard of Oz,” the 1939 MGM classic that made her a star.

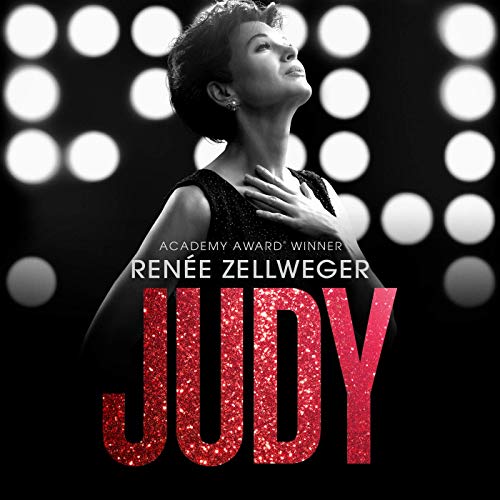

The timing then is perfect for “Judy,” a new bio pic, starring Renee Zellweger and based on the acclaimed 2012 Broadway production of playwright Peter Quilter’s “End of the Rainbow.” The new film in theaters now, directed by Rupert Goold with a screenplay by Tom Edge, sets out to deepen and expand the limited framework of the theatrical play and it does so masterfully.

One key ingredient is the addition of Rosalyn Wilder, the real-life woman (played by Jessie Buckley) who looked after Garland during her tumultuous five-week engagement at London’s Talk of the Town, a three-tiered supper club and the former home of London’s Hippodrome theatre. The producers of “Judy” tracked Wilder down via a Garland fanzine interview and hired her on as a consultant. The script’s addition of Wilder’s memories of her daily interactions with the star reveal Garland’s sense of humor, coupled with her unpredictable mood swings and her emotional and physical fragility.

Photo Credit: David Hindley, Courtesy of LD Entertainment and Roadside Attractions

Unlike the bombastic baby rattle to bedazzled rock star story arcs of other recent music bio pics like “Bohemian Rhapsody” and “Rocket Man,” the power of “Judy” lies in its intimacy.

Despite some wonderful production numbers shot on location at London’s Hackney Empire, a scaled down theatre also designed by Hippodrome architect Frank Matcham, “Judy” is at its essence, an intense character study of a superstar in winter who would flame out by summer.

The film zeroes in on the five weeks Garland spent on stage in London, engaging and aggravating her devoted fans and her late-night booze and pill littered emotional breakdowns alone in her hotel suite between performances. Thanks to a series of fascinating and frightening flashbacks to Garland’s teenage years at MGM during the making of “Oz,” the beginning of and the finish of the star’s career, bookend and anchor the film.

Based on incidents from Garland’s teen years spent on set at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (Darci Shaw portrays the younger Judy), the film’s flashback sequences supply the structural scaffolding for the adult Garland’s troubled life, from her 18-hour days on set and the studio-administered pills supplied to amp her up to work and to knock her out to sleep, to the verbal abuse she received, even as she emerged as one of the studio’s biggest stars.

When she attempts to flex some of that star power on-set, Louis B. Mayer tells her (in a chilling performance delivered by Richard Cordery), “You know who you are? You’re Frances Gumm. Your father was a fa**ot and your mother only cares about what I think. That’s who you are. Don’t ever hold up another movie of mine.”

When we’re introduced to Garland in late 1968, she’s homeless, performing on stage with her kids, Lorna and Joey for $150 in cash and unable to pay her hotel bill. After the crash and burn of her weekly 1963-64 CBS TV variety series “The Judy Garland Show” (CBS hired the Hollywood superstar to help them counter-program against NBC’s runaway hit western “Bonanza” on Sunday nights), a disastrous concert tour of Australia and being fired from the film adaptation of Jacqueline Susann’s “Valley of the Dolls,” Garland can’t find work to pay off tax debts. Adding to her angst, ex-husband Sid Luft, is suing her for custody of the kids.

“I’m unemployable and uninsurable,” Zellweger as Garland says early in the film. “And that’s what the ones who use me say to my face.”

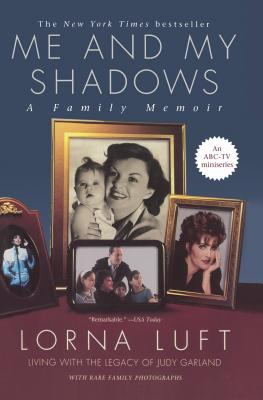

But she’s still beloved in London and The Talk of The Town is willing to pay her $6,000 a week for a five-week engagement. While it means leaving her two youngest children behind in Los Angeles. Garland takes the work as a way to earn money and re-introduce some stability into her childrens’ lives, reluctantly leaving them with their father. The film’s idyllic version of events is in stark contrast to reality. In her 1999 memoir “Me and My Shadows: A Family Memoir” daughter Lorna Luft recalled the night her younger brother Joey left their mother’s home for good after an impaired Garland, possibly not knowing who he was, hurled a butcher knife at her son while chasing him out the door.

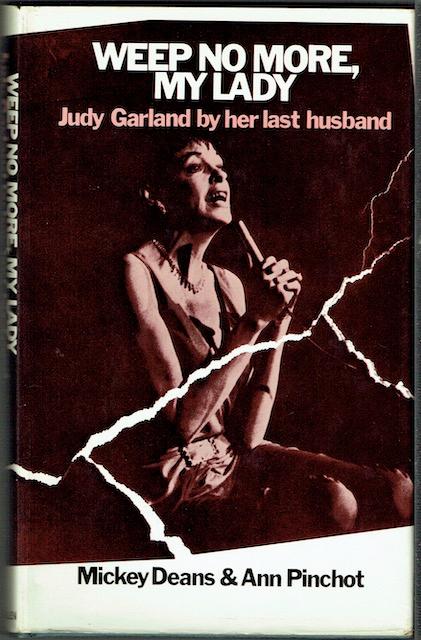

The performer’s oldest daughter Liza Minnelli is off embarking on her own career but becomes a pivotal plot point in “Judy.” Minnelli (played by Gemma-Leah Devereux) is throwing a party when her mother unexpectedly arrives and ends up being introduced to nightclub manager and musician Mickey Deans, the younger man who will become Garland’s fifth and final husband. The meeting is a romanticized rewrite of the way the pair actually met — when Deans delivered a bottle of pills to the singer’s hotel room in the middle of the night while posing as a doctor in front of Lorna and Joey.

In his 1972 memoir “Weep No More, My Lady,” Deans recalls while packing for London, Garland was so broke she couldn’t pay the $35,000 to release her own musical arrangements to her for the engagement. Deans, a pianist, lifted the arrangements from her recordings instead.

As a terrified Garland battles self-doubt backstage on opening night at Talk of the Town, “Judy” effectively gets filmgoers emotionally in the star’s corner. When Zellweger tentatively steps on stage and opens with “By Myself,” the song Garland performed in the 1963 Hollywood melodrama “I Could Go On Singing,” both the Talk of the Town and movie audiences are enthralled and more importantly, invested.

Zellweger doesn’t play Garland as much as summon her spirit into her body.

At times, it’s eerie how much she embodies the late star, down to her facial tics and a quirky head scratching mannerism the singer first displayed on her weekly CBS TV series. Zellweger studied YouTube clips of the show incessantly, even practicing along with the video Garland as her TV performances played in a mirror. Zellweger completely disappears into the role as effectively as Meryl Streep slipped into Julia Child’s apron in 2009’s “Julie and Julia.” “Judy” costumers even designed Zellweger’s outfits to accommodate Garland’s slightly hunched back, due to scoliosis, forcing the actress to adapt to Garland’s posture.

Playing Judy Garland is ideal for Zellweger, who gets to fuse her Oscar-winning “Cold Mountain” drama skills, her “Chicago” musical chops with her flair for comedy that gave Hollywood two hit “Bridget Jones” films.

For the film’s soundtrack, Zellweger does all of her own singing, wisely choosing not to mimic the inimitable Garland voice. And that’s really the key to “Judy’s” success as a film. While Garland herself often ran the risk of becoming a self-caricature, Zellweger keeps her performance grounded and small, resisting the hysterical histrionics that Garland herself frequently succumbed to. It’s an intimate performance designed for the big screen, sometimes reduced to facial expressions where, occasionally for a moment or two throughout the two-hour film, Bridget Jones’ eyes peek through on screen.

Photo Credit: David Hindley, Courtesy of LD Entertainment and Roadside Attractions

“Judy,” unfortunately, also illustrates how much Hollywood hasn’t changed for women over the last half century. After making millions for MGM, Garland, lost her house and had taken to sneaking out of hotels in the middle of the night to avoid paying her bill, all by the age of 47. Zellweger, likewise, made millions for the studios, spending most of her 30s making a series of non-stop hits, including “Jerry Maguire,” but in recent years, has quietly slipped off the radar in Hollywood. Perhaps, not coincidentally then, the script for “Judy” resonated with Zellweger, who was 47 when she received it.

After collapsing during her run at Talk of the Town, Garland is ordered to get cleared by a physician before returning to the stage. The result is a wonderful exchange illustrating how Garland interacted with us mere mortals off stage. “You’re a little underweight,” observes the doctor to which Garland replies, “You’re flirting with me now.”

The physician then concedes, “I had an absolute thing for Dorothy Gale.” “A lot of the boys loved her pigtails,” says Zellweger as Garland. “Well, for me, it was the way she took care of her dog.” Judy’s reply: “You might be the most English man I’ve ever met.”

The film also neatly sidesteps painting actor Finn Wittrock’s nuanced portrayal of Mickey Deans into a stock movie villain. Like in life, “Judy” attempts to portray the couple’s complicated relationship in all its dimensions.

Deans’ account of their relationship in his long-out-of-print memoir, “Weep No More, My Lady,” offers a fascinating and occasionally troubling account of their time in England together as the clock was running out on the singer’s life. After the high maintenance star was abandoned by nearly everyone, Deans was the sole eyewitness to Garland’s final months, time that was largely spent together quietly in a small mews cottage on a cul de sac in London’s Chelsea neighborhood.

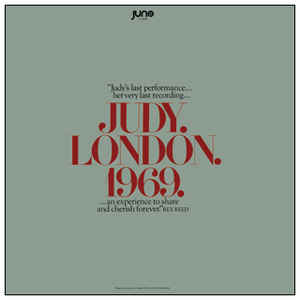

And while there’s an official “Judy” soundtrack featuring vocal performances by Renee Zellweger of some of Garland’s most closely identified songs, thanks to Deans, fans also have a largely forgotten final live recording from the singer. Released as “Judy. London. 1969.” on the indie record label Juno, the ten-track collection was recorded by Deans on a battery-operated tape recorder in Talk of the Town’s second balcony on Garland’s closing night.

Deans was hoping to allay the singer’s fears about venturing back into the recording studio with her now-depleted voice (at the time of her death, Garland, previously signed to Capitol Records and later, ABC Records was without a record contract for the first time in 15 years). Explained Deans in a letter to Talk of the Town producers that was printed on the back cover of the LP: “These tapes were made solely to convince my fearful Judy that the crashing applause was deserved and that she was giving a performance that she could take pride in.”

After taking her final bow, Garland was so pleased with how she sounded on the recordings, the couple stayed up all night listening to them. First thing the next morning, they turned up in the hotel suite of Talk of the Town show producers Robert Colby and Ettore Stratta to play them over and over for them. In 1971, Rex Reed would be nominated for a Grammy for his album liner notes for the posthumous project.

Like Billie Holiday’s gin and string soaked penultimate 1958 album “Lady in Satin,” newcomers to “Judy. London. 1969.” might find the condition of Garland’s voice a bit jarring.

In his liner notes Reed writes, “Sometimes the voice was tired and rough around the edges. It would bend and crack and she’d sip something cool (we were never quite sure what it was) and then it would soar again, like a turbo jet readying for a transatlantic take off.”

The final moments of “Judy” seek to recreate that same triumphant take off to end Garland’s run at Talk of the Town. Filmmakers tweaked the timeline a bit and borrow an earlier emotional moment from Garland’s professional life, adding it to the film’s finale to supply a bigger, more uplifting ending.

Six months later, on the morning of June 22, 1969, Deans would find her inside a locked bathroom, her arms on her lap with her head resting in her arms, dead from an accidental overdose of barbiturates.

Fueled by a tour de force performance by Zellweger, 50 years after her death, “Judy” could help introduce modern movie goers to Garland, whose only reference point to “A Star Is Born” is the 2018 version, starring Lady Gaga. Outside of Atlanta-based Turner Classic Movies regularly scheduled rotation of her filmography, Garland’s work has largely been forgotten.

Life-long Garland acolytes, who, like the fictitious gay couple portrayed in “Judy,” have erected shrines to the star in their homes, the film may prove an emotional heavy lift. While it ultimately serves as a celebration of Garland’s career, “Judy” never shies away from the inherent darkness of the performer’s final months.

But make no mistake, Renee Zellweger’s riveting performance is the centerpiece and the reason to seek out “Judy,” now open at select theaters across the country. Her final scenes are so powerful, movie goers may find themselves needing a few moments to sit in the dark in silence and stare at the credits while fully absorbing it.

It might well inspire you to crank Zellweger’s rendition of “Get Happy” from the “Judy” soundtrack on Spotify on the drive home, too.

Or better yet, Judy’s.

In Atlanta, “Judy” is now playing at AMC Phipps Plaza 14, AMC Parkway Pointe 15, AMC Barrett Commons 24, AMC Colonial 18, CMX Cinebistro Halcyon 9, Regal Avalon 12, Regal Tara 4 and Springs Cinema and Taphouse.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.