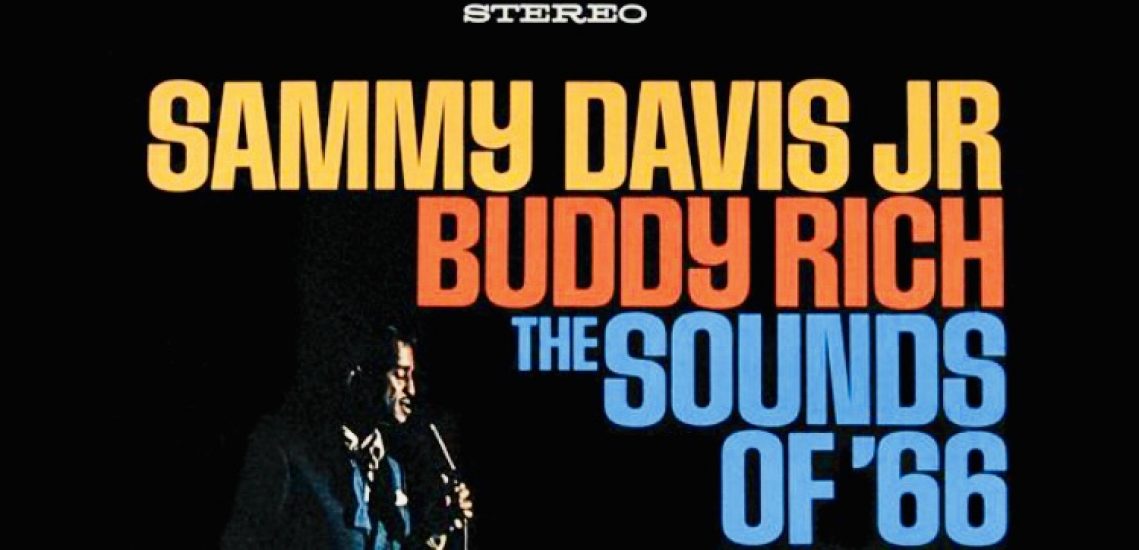

Sammy & Buddy at The Sands: The Inside Story of the Las Vegas Live Recording You’ve Never Heard

According to Jimmy Bowen, one of the best live albums ever recorded in Las Vegas nearly didn’t happen. The Reprise Records producer who had just delivered chart-topping hits for his boss Frank Sinatra and his pallie Dean Martin via “Strangers in the Night” and “Everybody Loves Somebody” at the height of Beatlemania was hoping lightning would strike a third time with another member of the Rat Pack, Sammy Davis Jr.

But Bowen was cooling his heels inside a Las Vegas rehearsal studio with an increasingly irritated Buddy Rich and his 15-piece big band, who had just opened with a bang at the Aladdin hotel and casino down the street. The group had assembled to run down 10 brand-new arrangements written by Sammy’s conductor George Rhodes and Reprise arranger Ernie Freeman in preparation for a late-night live recording featuring the two powerhouse entertainers.

There was just one problem. Sammy was a no-show.

“Buddy was 30 minutes early to rehearsal and Sammy was 30 minutes late,” remembers Bowen. “Buddy was so pissed that when Sammy came in the front door, Buddy ducked out the back.”

Eventually, Bowen was able to talk the agitated drummer back inside the studio to rehearse with Davis, his friend of two decades, who used to pal around together with fellow jazz performer Mel Torme when all three were cutting their show business teeth in the 1940s.

We were eating raw meat in those days. Sammy introduced Buddy, Buddy started playing and we just took off.

Says Bowen: “Sammy and Buddy went head to head and then they hugged and that was the end of that. Then we got down to business.”

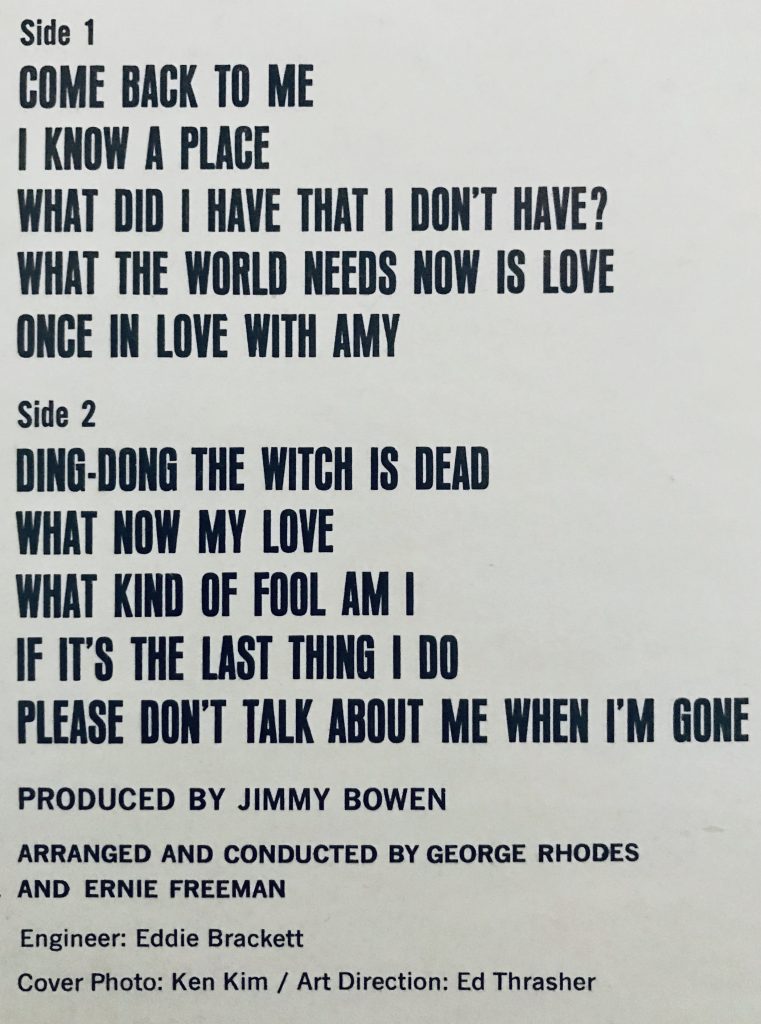

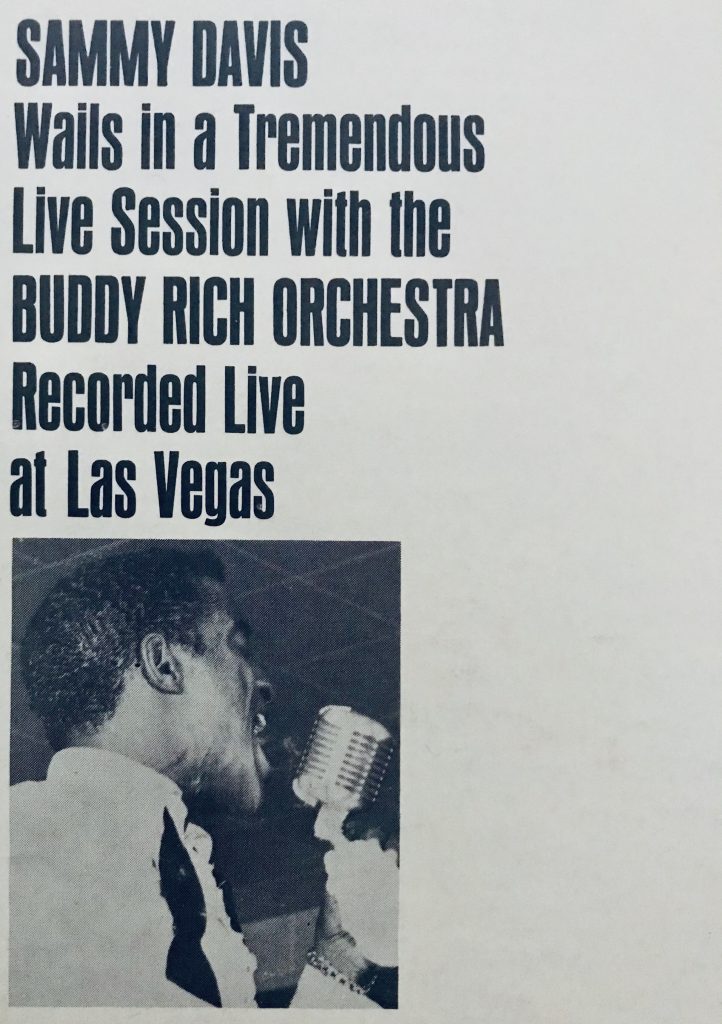

The business at hand? Two private late-night invitation-only gigs featuring Davis and Rich and his big band at the Sands Copa Room for a Reprise Records live project featuring the pair, “The Sounds of ’66.” The set of brand new blistering up-tempo charts written by Rhodes and Freeman were big band jazz arrangements of “Come Back to Me” and “What Did I Have That I Don’t Have?,” two tunes from the new Broadway hit musical “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever,” the Burt Bacharach-Hal David hit “What The World Needs Now Is Love,” the new Petula Clark single “I Know a Place” and a decidedly small fry adverse treatment of “Ding-Dong The Witch is Dead” from “The Wizard of Oz” among five other standards.

Bowen’s plan was to record the project over two nights after Davis had finished up his two sets at the Sands and Rich and his band had concluded their sets down at the Aladdin. Bowen and Reprise Records engineer Eddie Brackett had miked the Sands show room and were positioned two floors over the main stage with a three-track recording console. Sammy had sent out invitations to the other performers working on the Las Vegas strip so the crowd was packed with dancers, singers, musicians, bartenders and other friends.

“This is a very special night,” Sammy told the capacity crowd. “This record is being recorded as I look at my watch now, it is quarter after 5 and Las Vegas, is still swinging. For the next 10 or 12 sides, just relax and swing with us if you will. Any noises that come from the audience or any side noises you might hear, know that they are not canned, they are live.” The crowd proceeded to cheer as Sammy called on his conductor to light the musical fuse: “GO, George!”

Buddy Rich and the band then sent the crowd into the stratosphere, parting the audience’s Brylcreemed hair with a high octane, high octave horn arrangement of “Come Back to Me” as Sammy swung the showtune lyrics and Buddy brutalized his drum kit.

“We were eating raw meat in those days,” says Tony Scodwell, lead trumpet on the session, who was in charge of the Buddy Rich brass section. “The horn parts didn’t intimidate us because the band was in terrific condition. Sammy introduced Buddy, Buddy started playing and we just took off. We were smoking.”

Barry Zweig, who was 24 at the time, played Gibson guitar on the dates. “We were keeping pretty big company,” says Zweig. “I wouldn’t say we felt under pressure but we were all on our toes and determined to do our best. For my money, Buddy played better on that record than he did on the solo album [‘Big Swing Face’] we recorded later that year live at the Chez [in Hollywood]. It was exciting, man. Everyone just fed off one another.”

Upstairs, Bowen and Brackett were knocked out. “From the rehearsal, I knew what we had,” remembers Bowen. “With Sammy and Buddy, it was like combining nitroglycerine and gasoline and striking a match. Buddy had such energy bursting out of him. Sammy did too. The audience just lit up. With live recordings at that time, you’d occasionally have to take the tapes back into the studio and do some tinkering. With that record, all we did was splice together the best performances from the two shows and press it up.”

A single photograph remains from the “Sounds of ‘66” sessions. For fans who have only ever heard the recording over the past 53 years, one detail on stage sticks out — the music stand in front of Sammy Davis Jr. Says Scodwell: “We ran down those arrangements maybe once or twice. Buddy didn’t read music so he listened to the charts and that was it. They were locked into place in his head. As far as I know, Sammy hadn’t seen the charts in advance either. But you’d never know it listening to that record. Sammy was a consummate entertainer. And after those two shows, we never saw those charts again.”

Having an audience full of show biz pros (“Tony Bennett was in the front row cutting up with Marty Flax, one of the saxophonists and one of the wittiest guys I ever played with,” recalls Zweig) came in handy when Bowen suddenly detected a technical snafu upstairs.

“Somebody had knocked one of the microphones,” says Bowen. “I ran down two flights of stairs and stood in the wings and yelled, ‘Sammy, problem!’ Cool as you please, Sammy cut off the band and announced to the crowd, ‘Ladies and gentleman, we’ve experienced technical difficulties and we’re going to start this one over for you.’” Bowen says at the conclusion of the set, Davis, Rich and company received a standing ovation.

“The Sounds of ‘66” doesn’t contain many ballads but Barry Zweig made the most of the shows’ occasional mezzo piano moments. Zweig’s tasteful guitar work shines on the opening stanzas of “What Now My Love” and he manages to musically hang on for dear life during Davis’ finale “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone” when the chart calls for him to riff behind the singer as Sammy starts “preaching” to the cheering, enabling crowd.

“Our parts were mostly written out,” says Zweig. “But when Sammy started talking, we just followed along. He knew exactly where he was going and we followed him. It was just exciting sitting there and being a part of such an iconic project.”

“The record comes to its exciting head with the rapid patter of “Ding-Dong the Witch is Dead,” says Dan Buskirk, who’s hosted “Jazz With Dan Buskirk” on Mondays from 11 am to 2 pm on WPRB-FM in Princeton, N.J. for the past 18 years. “But just as Sammy knows how to end a live set, he knows how to end an album too, closing with ‘Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone’ with a fire that guarantees him the opposite effect. For me, this album is a dazzling highpoint of both Rich’s and Sammy’s storied careers.”

I needed that. That record really helped to establish us.

When Jimmy Bowen played the master tapes for Davis, he danced around the studio. But Rich’s reaction was tougher to read. The drummer later confided to his friend and biographer Mel Torme, “The Sounds of ‘66” was an asset as he was attempting to get a foothold in Vegas, a town where jazz was a tough sell to the casino set. In “Traps The Drum Wonder: The Life of Buddy Rich,” Torme writes, “‘I needed that,’ Buddy confessed. ‘I was beginning to have doubts that I could ever get my new band off the ground. That record really helped to establish us.”

Sid Mark, whose nationally syndicated “Sounds of Sinatra” radio show beams out to nearly 100 radio stations weekly, still remembers receiving an advance DJ copy of “The Sounds of ‘66” LP when it arrived at WHAT-FM, the Philadelphia jazz radio station where he was working.

“I was pretty friendly with Sammy but he never said, ‘Look out for this one!’” says Mark. “I remember putting on Side One and hearing ‘Come Back to Me’ and saying, ‘Oh my God!’ It was the consummate combination of the two. You could hear Sammy’s swagger on that record. Sammy was one of those people who as Sylvia Syms used to say, knew how to ‘take the stage’ as opposed to walking onstage. And it captures Buddy’s bigger than life personality. Here was a guy I was sitting with once when he was approached by a young fan asking Buddy to sign his drum sticks, saying, ‘Buddy, I want to be just like you when I grow up.’ Buddy told him, ‘Kid, you’ll never be like me.’”

Mark put “Sounds of ’66” on the air immediately and listeners loved it. The record remains a favorite he continues to play 53 years later on his weekly show.

Naples, Florida-based singer and guitarist Paul Penta was a high school musician growing up in Boston when he walked into a record shop and first encountered “The Sounds of ’66.” Penta was a Sammy Davis Jr. fan but four measures of Buddy’s Rich’s drum work on the LP’s opening track turned Penta into a life-long Rich fan as well. “Those drum fills are like thunder and lightning,” says Penta. “When Buddy bangs out those two incredible measures of drums, you can actually hear the crowd getting caught by surprise. This is a Sammy Davis performance filled with Sammy acolytes at the Sammy altar and Buddy starts playing and puts the crowd on its ear. I was hooked immediately.”

A few months later, Penta took his copy of the LP up Route 1 to Peabody, Mass. to see Rich and his big band play a Sunday matinee at the 56-seat Lennie’s on the Turnpike, a jazz club so small band leader Stan Kenton famously exclaimed upon entering the venue, “This is the first time I’ve ever played under a bed.”

Penta waited until Rich was taking a break between sets before approaching him with his copy of the album and a pen. The notoriously cantankerous drummer initially wasn’t impressed. “Buddy grabbed it and said, ‘This isn’t even my album!’” recalls Penta with a laugh. “But he signed it for me.” Then Penta received an unexpected invitation when Rich asked, “Hey kid, you smoke?” A minute later, Penta was out on the front porch of the club smoking a cigarette and shooting the breeze with his musical idol. “It was a private moment with a cool guy,” Penta reflects now, over forty years later as a working musician himself. “I met the nice Buddy Rich that day.”

While a hit with die hard jazz fans, “The Sounds of ‘66” was a modest seller for Reprise Records and practically everyone involved in the record promptly moved onto other projects. “I was producing 25 records a year at that point,” says Jimmy Bowen. “You’re like a jockey. You just moved onto the next horse.”

Davis and Bowen wouldn’t strike platinum together on the charts for two more years when in 1968, Bowen found the civil rights activist a tune titled, “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” a signature song that would remain in the performer’s repertoire until his death in 1990.

Paul Penta has a theory about why the recording had a short shelf life for many record buyers: “This is just me spit balling but I think they blew it with the title of the album. It automatically dates the album. Your first reaction is ‘Sounds of ‘66’? Who cares about 1966.’ Plus, there are very few hit jazz albums out there that manage to make an impact with a mainstream audience.”

Bowen, who would go on to make Reba McEntire, George Strait, Hank Williams Jr. and a guy named Garth Brooks household names while overseeing MCA and Capitol Records in Nashville in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, didn’t listen to “The Sounds of ‘66” again until he retired to Maui and was re-listening to his catalog while writing his 1997 memoir, “Rough Mix.”

“I spent a couple of years listening to all of the records I produced,” recalls Bowen. “There were a few where I said, ‘I don’t need to ever hear that again’ but when I got to ‘The Sounds of ‘66’ I went, ‘Damn, that was good!’” The record would remain in heavy rotation at the producer’s home.

Likewise, Tony Scodwell, who, these days manufactures his own brand of trumpets, didn’t think about the recording again until he was on tour with trumpeter Doc Severinsen in the mid-2000s and a fellow musician inquired about the sessions. Scodwell went into a record shop and ordered a CD copy. “I was really taken aback at how good it was,” says Scodwell. “Today, every record is flawless to the point of sounding sterile. [‘The Sounds of ‘66’] is raw and real and the musicianship shines.”

After being out of print for nearly 30 years, the album was finally issued on CD in 1996 and again in 2004 and today is readily available on Amazon and the streaming service Spotify, along with vintage vinyl mono and stereo copies listed on eBay.

There’s no way I could have screwed it up if I’d tried. We just hung the mics, rolled the tape and received it.

“I’m glad it’s out there and that people are still discovering it,” assesses Bowen. “You wind up putting a little piece of yourself into each of these records. I’d like to take credit but there’s no way I could have screwed that one up if I had tried. We just hung the mics, rolled the tape and received it. I never judged the quality of anything I worked on by how many copies it sold. For me, it’s about whether it holds up and whether people liked it. I’m real glad my name’s on that one.”

Special thanks to the many musicians and fans who are a part of the 2,400-member Facebook Group Buddy Rich Road Stories, who helped in the research and reporting of this story.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.