‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ Director Barry Jenkins on the film’s UGA Connection and Why He Altered the Iconic Novel’s Ending

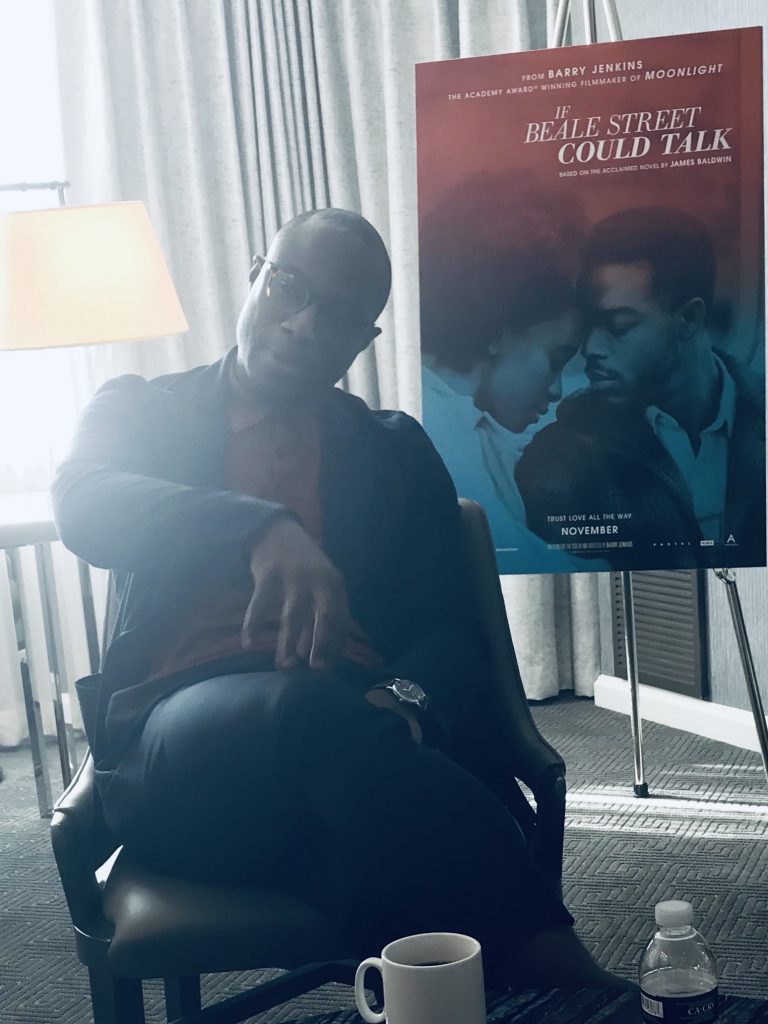

As the lights came up last fall at the advance screening of “If Beale Street Could Talk,” the film’s director and screenwriter Barry Jenkins spotted a familiar face in the Atlantic Station movie theater — University of Georgia English and African-American Studies professor Ed Pavlic.

After seeing Jenkins’ 2008 indie feature “Medicine for Melancholy,” Pavlic had invited the young filmmaker to Athens to talk to his class. Afterward, Jenkins explained to Pavlic that he had adapted the James Baldwin’s acclaimed 1974 novel while on a working vacation in Europe, a trip that also produced a screenplay of a story by Tarell McCraney called “Moonlight.”

Jenkins had one small problem – he had written the screen adaptation on a whim without permission from the James Baldwin estate. He asked Pavlic, the author of “Who Can Afford to Improvise?: James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners” (Fordham University Press, 2015) and the forthcoming “No Time to Rest: James Baldwin’s Life in Letters to His Brother David” if he had any Baldwin estate contacts he could share.

“He gave me one email address and one mailing address,” the Oscar-winning filmmaker explained to the audience. “So I sent the script that I had absolutely no rights to to that address in a package.” A week later, Jenkins received a reply on Baldwin estate letterhead informing him that they were familiar with his work and they were interested but to “buckle up” for a lengthy process.

“Five years later, he we are,” said Jenkins, asking Pavlic to stand up and be recognized as the audience applauded. “This movie wouldn’t exist without him.”

In the afterglow of his 2017 Best Picture Oscar win for “Moonlight,” Jenkins set out to film the first English language film adaptation of a James Baldwin novel. Last fall, Jenkins and the cast, including newcomer KiKi Layne, who plays Tish Rivers in the film and Regina King and Colman Domingo, who portray her parents, Sharon and Joseph Rivers set off on a multi-city tour to promote the film.

The film’s male lead, Stephan James, who plays the film’s falsely accused Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt, will be instantly recognizable to Atlantans, having played civil rights icon John Lewis in director Ava DuVernay’s 2014 locally shot “Selma,” co-starring Domingo as MLK aide Ralph David Abernathy.

King has already won a Best Supporting Actress Golden Globe for her role and she’s now up for an Oscar and the film is also nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Original Score.

But for Baldwin’s legion of readers worldwide, Jenkins’ flash-forward alternate ending shot for the film adaptation raised a few eyebrows. In an interview with Eldredge ATL, Jenkins explained that he did, in fact, film Baldwin’s ending but it left him unsatisfied as a viewer.

“Part of it is, when you read a book, it’s maybe a 20-hour process,” reflects Jenkins. “When you get to the end of the novel, that softer, more open ending can have a larger effect because you’ve been so inside the material and the characters for so long. When you watch a film, it’s two hours. When I put myself in the audience’s shoes watching it, it just felt like there was something missing. To go on that journey with those characters and not end up in a place that was clear and definitive wasn’t satisfying for me.”

Jenkin’s solution was to move the action forward five years where viewers get a glimpse of Fonny and Tish’s future. Says Jenkins: “I wanted to find a very grounded way to end the film that spoke to what I felt when reading the book, which was this — the lives of black folks in America have always been, from the very beginning of our time in this country, rooted in some level of despair and suffering. And yet, there’s always been joy. We found a way to find joy and love and family and community. And so, I wanted to acknowledge the dire circumstances of Fonny’s situation and present a realistic outcome, given how heavily manipulative the system is to young men like Fonny. I just wanted to end the film on a very grounded symbol of hope. It’s five years in the future and there is a clear, defined future for these people. I don’t think any of these characters will be the same people they were before the film began. But I do think, generationally, that this child will be stronger and have a better life than his father’s generation. And that’s been the story of black folks in America for generations.”

While Baldwin’s novel was published in 1974, the book and the film’s themes of racial inequality within the prison system, police corruption and police brutality set against the backdrop of a strong united black family resonate just as powerfully in 2019. Now, with a Best Picture Oscar on his mantel, Jenkins is using his new A-lister leverage in Hollywood to amplify Baldwin’s work.

“The end game, for sure is getting people to read James Baldwin,” says Jenkins. “That’s the biggest thing for me. Reading this book and now making this film, as you said, so many things that happen to these characters are so relevant to today. James Baldwin was a very perceptive and wise man. I’m not sure what the audience is for this film but I do know that Baldwin wrote for everyone, he spoke to all of us. There were things in the soil, in the root of this that are very particular to the black experience but not exclusive to the black experience. What Baldwin is saying to us is these systems — that now we’re realizing because of Twitter and social media and a very aggressive news cycle — these problems have persisted for so long and these systems have been corrupt for so long and that’s why the themes at the center of the film are still so relevant today. With this film, you’re forced to think about it. There is nothing in this book or in this film that’s not the truth.”

I had the great pleasure of interviewing Barry Jenkins with former VOX teen staffer and current Savannah College of Art and Design arts editor and filmmaker Mikael Trench and current VOX teen staffer Tyler Bey. You can read Mikael’s coverage of the film junket here and his film review plus check out Tyler’s personal reflection on the voxatl.org website.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” is in theaters now. The 91st Academy Awards will be presented on Feb. 24, starting at 8 p.m. on ABC.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.