“Serial Black Face” Playwright Janine Nabers Transports Atlanta Back To Its Darkest Hour In A Search For Closure

The first thing you encounter entering backstage at the Actor’s Express world premiere of playwright Janine Nabers’ “Serial Black Face” is a medical examiner gurney containing a body draped in a white sheet. Actor’s Express artistic director Freddie Ashley, who is brewing up some late-afternoon coffee, has dubbed it “the world’s saddest theatrical prop.” In two hours, Ashley and Nabers will oversee the final dress rehearsal for the world premiere of the drama set against the backdrop of the Atlanta Child Murders case in 1979. “I knew the moment I read Janine’s play that I wanted to produce it,” explains Ashley.

As an actor warms up his vocal chords in a faraway corner of the theatre, Nabers leads us up the stairs and into Ashley’s office where she closes the door and opens up about writing “Serial Black Face” and why its themes still resonate in the era of Black Lives Matter, Flint, Michigan, Trayvon Martin and Ferguson, Missouri.

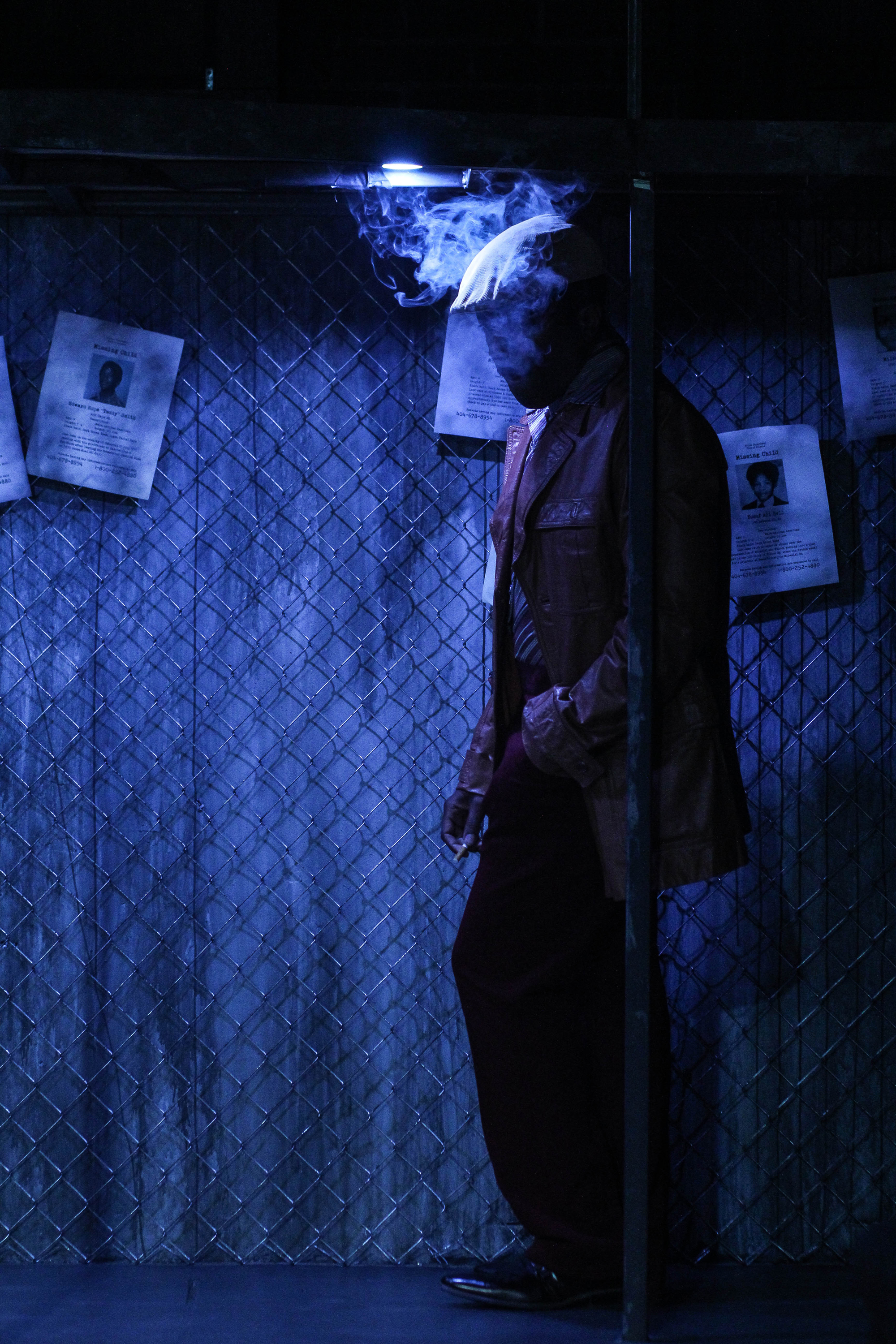

For Atlantans of a certain age, “Serial Black Face” expertly and tragically takes audiences back to the chain-smoking era of polyester shirts, disco-laced funk and a city in living in constant fear and mourning, holding its collective breath daily while waiting for the late TV news report that began gravely each night with, “It’s 11 o’clock, do you know where your children are?” Born in 1982, the same year Wayne Williams was sentenced to life in prison for two of the murders connected to the case involving more than 20 young people, Nabers first stumbled on Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered Children case in 2010 during a Google search.

“I was home visiting my parents in Houston and I pulled up a story on [former] Houston mayor Lee P. Brown and saw that he had been Atlanta’s [public safety commissioner] at the time of the killings,” Nabers recalls, placing her coffee cup on the floor beside her. One computer click later, Nabers was deep in the rabbit hole of the 35-year-old Atlanta Child Murders case. “I had never heard of it. I was completely blown away. I asked my parents, ‘What is this? What happened in Atlanta?’ They, of course, remembered the case because my older siblings were teenagers back then. It was a really scary time.”

One boy’s story in particular captivated the playwright — Darren Glass, who was 10 years old when he went missing in September 1980. He was the only missing child whose body was never found. “As a mother, how do you find closure when your child is never found?” Nabers asks. “That’s what opened the gate of curiosity for me.”

When “Serial Black Face” opens, Mechanicsville resident Sammy Cooper, a fictionalized stand in for Glass, is an 11-year-old who plays with G.I. Joes, has a Fat Albert & The Cosby Kids lunchbox and is missing. His mother, Vivian (Tinashe Kajese-Bolden), frantic and grieving, is faced with finding a job in order to support her remaining child, a teenage handful named Latoya (Imani Guy Duckette). In lieu of Wayne Williams, Nabers introduces danger into the play in a way that is guaranteed to lodge in the psyche of parents long after the lights come up in “Serial Black Face.”

In 2012 as Nabers began sharing an early draft of the play to friends and colleagues, one playwright friend asked, “Why are you doing this to yourself? This play is too dark.” Nabers recalls, “I wrote this play because I had to. People weren’t talking about this case and they weren’t talking about it for a reason.” And then Trayvon Martin was killed in Sanford, Florida. Nabers remembers, “It was history repeating itself, these cycles of inhumane acts.”

“Serial Black Face” got its first public reading in Atlanta at the Alliance Theatre in 2014 where it became a finalist in the Kendeda Graduate Playwriting Competition. Actress Jasmine Guy, who directed the 2014 readings and author-playwright Pearl Cleage, who led a post-reading conversation, became early champions of the work. The Alliance’s Celise Kalke then sent Freddy Ashley an email and an early draft of the play. “Serial Black Face” would go on to win the Yale Drama Series Prize.

“Celise said, ‘You really need to read this play,” Ashley recalls. “I instantly fell in love with it. The play doesn’t provide an aerial view of the Atlanta Child Murders case, but rather it looks at them from the inside out. So many people who lived here at the time still don’t want to talk about it. That just confirms to me more than ever the importance of producing this play and creating dialogue.”

On stage, “Serial Black Face’s” success hinges on the dynamic performances from Kajese-Bolden (best known to Atlantans for her work in “Blues For An Alabama Sky” at the Alliance) who plays Vivian and Guy Duckette as Vivian’s daughter Latoya (who performed in “As It Is In Heaven” at Atlanta Girls School and is making her professional debut in “Serial Black Face.” Her mother directed the Alliance reading of the play two years ago).

On stage, “Serial Black Face’s” success hinges on the dynamic performances from Kajese-Bolden (best known to Atlantans for her work in “Blues For An Alabama Sky” at the Alliance) who plays Vivian and Guy Duckette as Vivian’s daughter Latoya (who performed in “As It Is In Heaven” at Atlanta Girls School and is making her professional debut in “Serial Black Face.” Her mother directed the Alliance reading of the play two years ago).

“Tinashe has an instinct with this character that is profound and moving,” says Nabers, who was in Atlanta throughout the rehearsal process. “As a mother, she has a way into this woman’s life. She shows us the love and frustration and a connection of survival that is primal when you have a child. She’s allowed me to look at this character and at the play in a fuller way. She’s so incredibly determined to embody this character and make it sing through her voice.”

Nabers long-held fascination with Vladimir Nabokov’s envelope-pushing novel “Lolita” was an  inspiration for Latoya. Guy Duckette gives a haunting performance that, given her age, at times, can feel a little too real for some audience members. Says Nabers: “Let’s get one thing clear — Jasmine Guy is a powerhouse. Imani is the embodiment of that, too. She’s just so good. She’s so at ease on stage and has a ball of fire inside her that’s really amazing to watch.”

inspiration for Latoya. Guy Duckette gives a haunting performance that, given her age, at times, can feel a little too real for some audience members. Says Nabers: “Let’s get one thing clear — Jasmine Guy is a powerhouse. Imani is the embodiment of that, too. She’s just so good. She’s so at ease on stage and has a ball of fire inside her that’s really amazing to watch.”

The playwright says she understands the hesitancy from some longtime Atlantans who lived through the Missing and Murdered Children case about revisiting one of the city’s darkest hours. “If I had a family member that had been affected by this, I’d put this arm’s length as well,” says Nabers. “What I hope this play does is that it allows whoever has lived through it and not found closure to walk through the shoes of someone who feels the same way and who does find closure. To me, that journey, that sense of forgiveness is what ‘Serial Black Face’ is all about.”

Serial Black Face” runs through April 24 with performances Wednesdays-Saturdays at 8 p.m. and Sunday at 2 p.m. The performance runs 90 minutes with no intermission. For tickets and more info, visit actors-express.com.

Richard L. Eldredge is the founder and editor in chief of Eldredge ATL. As a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Atlanta magazine, he has covered Atlanta since 1990.